Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal

of peer-reviewed research and commentary

in the population sciences published by the

Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research

Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY

www.demographic-research.org

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

VOLUME 19, ARTICLE 19, PAGES 665-704

PUBLISHED 01 JULY 2008

http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol19/19/

DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.19

Research Article

Italy:

Delayed adaptation of social institutions

to changes in family behaviour

Alessandra De Rose

Filomena Racioppi

Anna Laura Zanatta

This publication is part of Special Collection 7: Childbearing Trends and

Policies in Europe (http://www.demographic-research.org/special/7/)

© 2008 De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta.

This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution

NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use, reproduction & distribution in any medium

for non-commercial purposes, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit.

See http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/

Table of Contents

1 Introduction 666

2 A profile of low fertility 670

3 The proximate determinants of fertility 676

4 Explaining low fertility in Italy: micro and macro determinants 679

5 Societal conditions impacting fertility and family 682

5.1 Lack of labour market flexibility 683

5.2 An unbalanced gender system 687

5.3 The ‘delay syndrome’ 689

5.4 Too much family 690

5.5 Too much Church and too little religiosity 691

6 Family policies 692

6.1 Financial support 693

6.1.1 Indirect financial support 693

6.1.2 Direct financial support 693

6.2 Social policies favourable to work-family reconciliation 694

6.2.1 Maternal leave 694

6.2.2 Parental leave 694

6.3 Flexibility of the labour market 694

6.4 Child care services 694

6.5 Policies of the present and recent past concerning

population and family

695

6.6 A short overview of the major political parties’ position on

fertility issues and policies

696

6.6.1 To reconcile work with personal and family life 698

6.6.2 Educational services for children and families 698

6.6.3 Investing in the future: an allowance for each child, a deposit

account for each young boy or girl

698

6.6.4 Solving the housing problem 699

7 Conclusion 699

References 701

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

research article

http://www.demographic-research.org 665

Italy:

Delayed adaptation of social institutions

to changes in family behaviour

Alessandra De Rose

1

Filomena Racioppi

2

Anna Laura Zanatta

3

Abstract

Considering its very low fertility and high age at childbearing, Italy stands alone in the

European context and can hardly be compared with other countries, even those in the

Southern region. The fertility decline occurred without any radical change in family

formation. Individuals still choose (religious) marriage for leaving their parental home

and rates of marital dissolution and subsequent step-family formation are low. Marriage

is being postponed and fewer people marry. The behaviours of young people are

particularly alarming. There is a delay in all life cycle stages: end of education, entry

into the labour market, exit from the parental family, entry into union, and managing an

independent household. Changes in family formation and childbearing are constrained

and slowed down by a substantial delay (or even failure) with which the institutional

and cultural framework has adapted to changes in economic and social conditions, in

particular to the growth of the service sector, the increase in female employment and

the female level of education. In a Catholic country that has been led for almost half a

century by a political party with a Catholic ideology, the paucity of attention to

childhood and youth seems incomprehensible. Social policies focus on marriage-based

families already formed and on the phases of life related to pregnancy, delivery, and the

first months of a newborn’s life, while forming a family and childbearing choices are

considered private affairs and neglected.

1

Sapienza Universita' di Roma. E-mail: alessandra.derose@uniroma1.it

2

Sapienza Universita' di Roma. E-mail: filome[email protected]

3

Sapienza Universita' di Roma. E-mail: annalaura.zanatta@uniroma1.it

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

666 http://www.demographic-research.org

1. Introduction

The Italian demographic panorama is dominated by very low fertility, very high levels

of life expectation, a negative sign of natural increase, and a positive balance between

immigrants and emigrants, with persistent regional variability (Table 1). These features

contribute to transforming the traditional image of Italian society, characterised by large

families, a high attachment to childbearing, with a long experience of emigration

toward richer and more industrialized countries.

Table 1: Recent demographic indicators by geographic area, Italy, 2005

Period TFR

(2004)

e

0

M

e

0

F

Birth rate

(x1000 in.)

Mortality rate

(x1000 in.)

Natural

balance

(a)

Migration

balance

(b)

Italy 1.33

77.6

83.2

9.7

9.8

-0.1

5.2

North 1.32

77.7

83.5

9.6

10.2

-0.6

8.3

Centre 1.28

78.1

83.5

9.4

10.4

-1.0

7.9

South-

Islands

1.35

77.2

82.7

10.1

9.0

1.1

0.1

Source: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

a Birth rate – Mortality rate.

b [(Total Immigrants- Total Emigrants)/Total Pop,]*1000.

Indeed, ‘zero population growth’ considered desirable by many political parties

after the Second World War is now a reality. Only thanks to a positive migration

balance Italy’s population is not yet decreasing. If we compare the total population of

1990 with that of 1 January 2005 (Table 2), we conclude that not much has changed.

However, the composition of the population has changed entirely in terms of age and

sex, and the proportion of the aged population has recently exceeded that of young

people. Projections for the near future forecast a decline in the Italian population: Even

though a recovery in fertility is hypothesized, a population decrease will be observed as

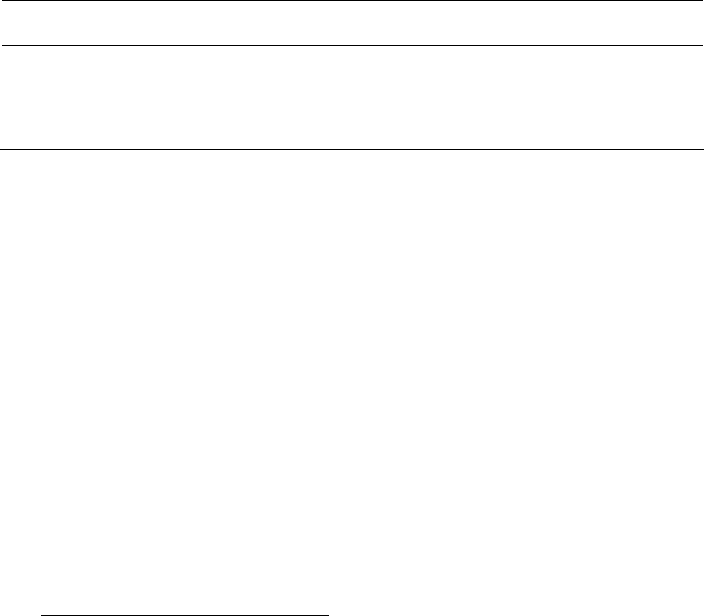

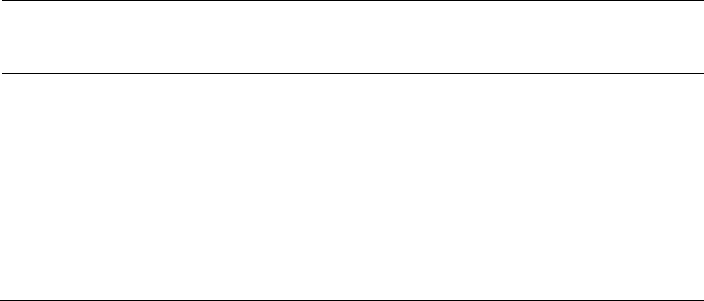

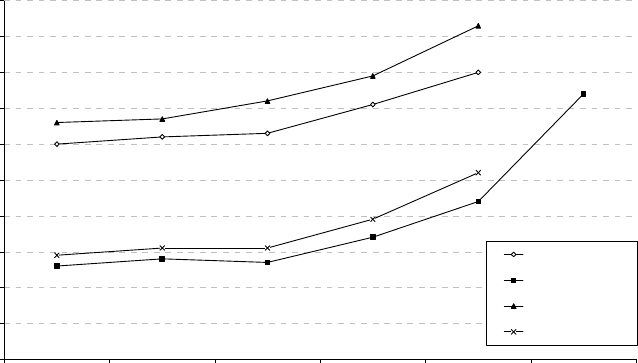

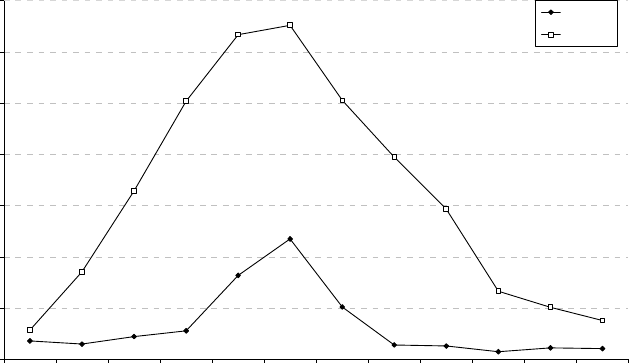

well as an increase in aging (Figure 1).

These prospects are valid, despite the expectation of a net annual addition of

120,000 migrants. The phenomenon of immigration to Italy, though relatively recent,

has now become crucial for the future of the population. According to official data

4

(Caritas /Migrantes 2006), 3,035,144 foreigners lived in Italy on 31

December 2005,

constituting an increase of 9% compared to the previous year, and a 126% increase

4

Official data refer to an estimation on the basis of resident population by ISTAT and other information from

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Interior Affairs.

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 667

compared to 2000. The foreign population represents 5.2% of the total population, but

the whole impact of migrants on Italian demography is difficult to assess, mainly

because the life span spent in our country by most foreigners has been relatively brief.

Table 2: Population size and structure indicators, 1990-2005

Population structure (%)

Population

size

(thousands)

0–14

15–64

65 and

over

Aging ratio

(P

65+

/P

0

-

14

)*100

Annual

growth rate

1990–2005

1,1,1990 56,719

16.8

68.5

14.7

87.6 -

1,1,2005 (a) 58,093 14.2

66.4

19.5

137.7 1.6 x 1000

Source: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

(a) estimates.

No more than 50,000 foreigners have lived in Italy for more than 10 years.

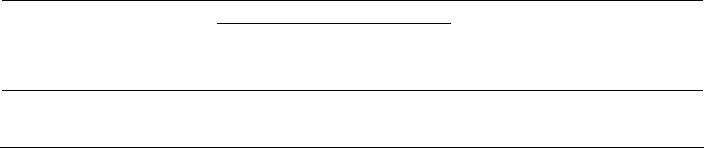

Nevertheless, we will speculate on the impact of migration on the population structure,

which is rejuvenated by foreigners who are relatively young (Figure 2), and its impact

on the number of births. Figure 3 shows a strong increase in the share of births due to

foreign (resident) population on the total number of births (8.7% in 2004). However, the

impact on the Italian fertility level appears insignificant: In 2004, the PTFR – calculated

on the total resident population – was 1.33, while that of Italian citizens only was 1.26.

At the same time caution is suggested while looking for the effect of migration on

fertility, for different reasons. First, we expect foreign women and couples, even those

from high fertility countries, to change their childbearing behaviour to that of the Italian

model. Second, the first reason for immigration is the search for employment, even

among women, and it is hard to reconcile this attitude with childbearing. Third, thus far

the relative size of the foreign population is not large enough to produce appreciable

effects on total fertility. Fourth, the ethnic composition is very heterogeneous, i.e.,

consisting of many different nationalities and distinctive cultural and religious groups

with different social and demographic structures and norms of behaviour, all of them

living in the same country. As we look at estimated fertility indicators by nationality

(Table 3), we notice, e.g., that while the mean age at childbearing among foreigners is

lower than 30, regardless of the country of origin (the only exception being Peruvian

women), the fertility levels differ very much among nationalities, and in some cases –

e.g., the Philippines and Peruvian – are close to the Italian level.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

668 http://www.demographic-research.org

Figure 1: Italian population (in thousands) and percentage of people

aged 60+by projection scenario, 1950-2050

40.000

42.000

44.000

46.000

48.000

50.000

52.000

54.000

56.000

58.000

60.000

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

Years

Thousands

Low

Medium

High

% 60+

2005

2015

2025

2035

2045

Low

25

.

6

29

.

9

36

.

0

43

.

4

46

.

7

Medium

25

.

6

29

.

3

34

.

4

40

.

3

41

.

7

High

25

.

6

28

.

8

32

.

9

37

.

6

37

.

3

Source: ONU, 2005.

Note: Low variant: recovery of fertility to 1,35 through the years 2040-45,

Medium variant: recovery of fertility to 1,85 through the years 2040-45,

High variant: recovery of fertility to 2,35 through the years 2040-45,

Net flow of 120,000 immigrants per year is hypothesized.

For the time being, trends in childbearing, even the most recent, have to be

explained within the framework of the Italian population and society, with its culture,

institutional, and economic structures, and the ambiguous net of relationships between

family and the Welfare State. In the rest of the paper, we aim to illustrate at least the

main aspects related to low fertility in Italy, starting with a detailed description of

recent childbearing trends.

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 669

Figure 2: Age structure of Italian population, including foreigners,

1 January 2005

600.000 500.000 400.000 300.000 200.000 100.000 0 100.000 200.000 300.000 400.000 500.000 600.000

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

10

men

women

foreign

foreign

Source: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

Figure 3: Percentage of foreigners out of total resident population

and out of total births

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Percent

Year

Resident population

Births

Source: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

670 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 3: Fertility of foreign women, ten most represented countries

of citizenship, 1999

Country of

citizenship

% of

female population

(age 15-49 out of a

total of 10 countries

Mean age at

childbearing

TFR observed in

Italy (a)

TFR observed in the

country of origin (b)

Morocco 19.9 27.5 3.4 3.4

Philippines 17.5 28.9 1.2 3.6

Albania 16.1 25.7 2.7 2.6

Romania 8.7 27.0 1.6 1.3

China 8.5 28.1 2.4 1.8

Peru 7.6 30.2 1.2 3.0

Poland 7.1 26.9 1.8 1.5

Tunisia 5.6 26.5 3.3 2.3

Brazil 5.5 27.1 1.6 2.3

Egypt 3.4 27.0 3.4 3.4

Source: ISTAT,Annual Report 2002.

(a) Estimated.

(b) ONU,1995-2000.

2. A profile of low fertility

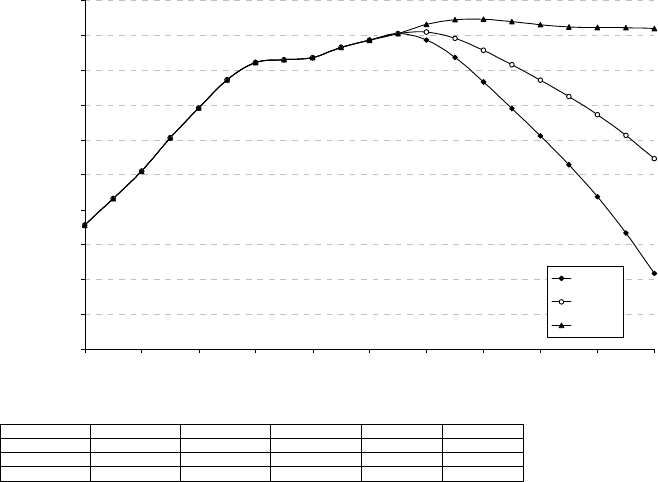

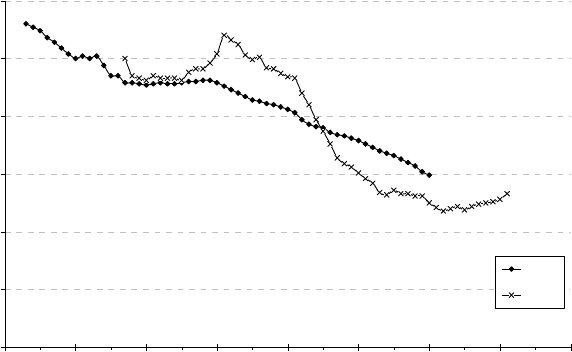

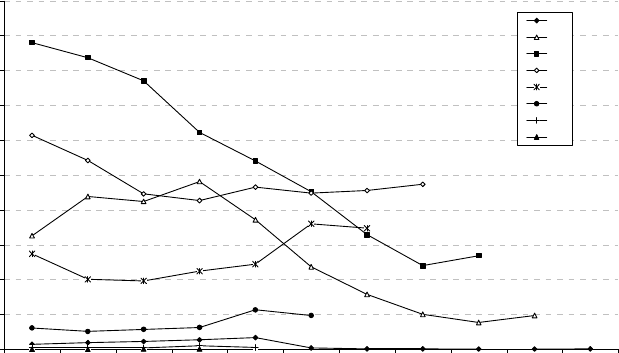

The decline of fertility is depicted in Figure 4. The Period Total Fertility Rate (PTFR)

fell below 2 children per woman in 1977, below 1.5 in 1984, and below 1.3 in 1993. In

the following decade, the PTFR was relatively stable around 1.25. It is only in very

recent years that we notice a slight increase in the level, which is, however, hardly

interpretable as a convincing sign of recovery in childbearing, mainly if we read these

data together with the continuous drop in completed fertility of female cohorts, from

2.28 children per woman in the 1935 cohort to 1.49 for the 1965 cohort.

The main features of this decline can be summarized as follows: first, a steady

decrease in the propensity to have a third or higher-order child and a more recent

declining propensity to have a second child; and second, the progressive delay in timing

fertility, starting with the postponement of first childbirth, accelerating the decrease in

period fertility levels.

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 671

Figure 4: Period (PTFR) and cohort (CTFR) total fertility rate, Italy

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

1905 1915 1925 1935 1945 1955 1965 1975 1985

CTFR

PTFR

Cohort

Period1933 1943 1953

1963

1973

1983

1993 2003 2013

Source: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

Figure 5 shows the dramatic decrease of third and higher-order total fertility rates,

but also a change in second-order fertility intensity due to cohorts of the 1950s and

younger cohorts. The youngest female generation of reproductive age even began to

refrain from having a first child. Indeed, the percentage of childless women is

increasing: For the 1945 birth cohort, it stood at a mere 10.2% while it reached 20% in

the 1965 birth cohort. As a result, the distribution of women by number of children born

has changed significantly (Figure 6): Women born between 1930 and 1950 experienced

a decline in childlessness and an affirmation of the two-child-family-model. This model

is progressively becoming less attractive for subsequent cohorts. In the 1960 cohort,

women with two children (37.2%) are outnumbered by the sum of mothers of an only

child (20.5%) and of childless women (24.2%); the figure for large families - namely

those with three or more children – stands at a mere 18.1%.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

672 http://www.demographic-research.org

Figure 5: TFR by order and cohort

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1920 1924 1928 1932 1936 1940 1944 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964

Cohort

TFR by order

1° order 2° order 3° order 4°+ orders

Source:

Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

Figure 6: Distribution of women by number of children ever born (%),

1930-60 cohorts

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960

Percent

0 1 2 3+

Source:

Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 673

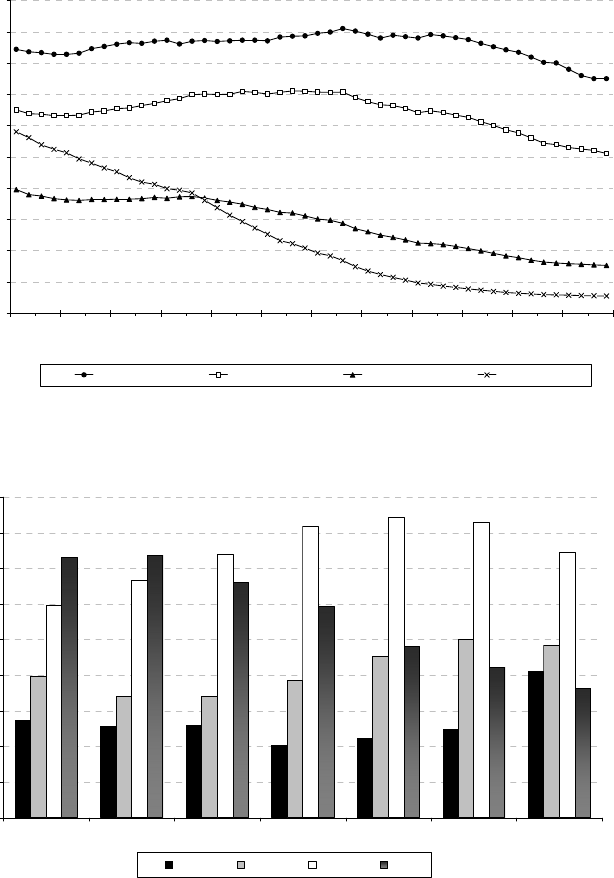

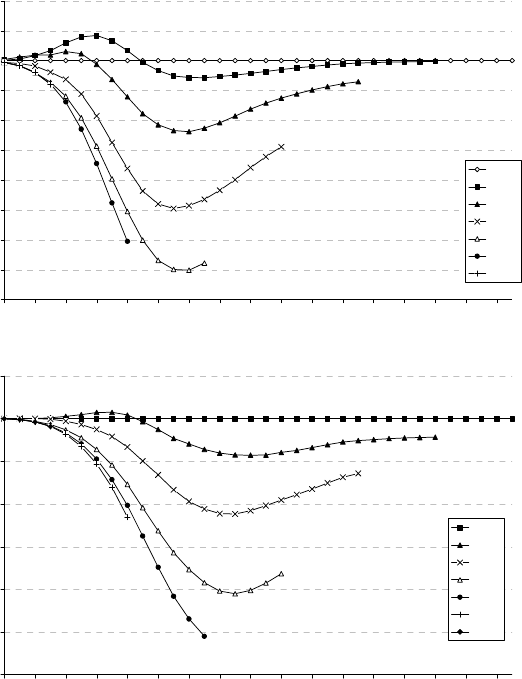

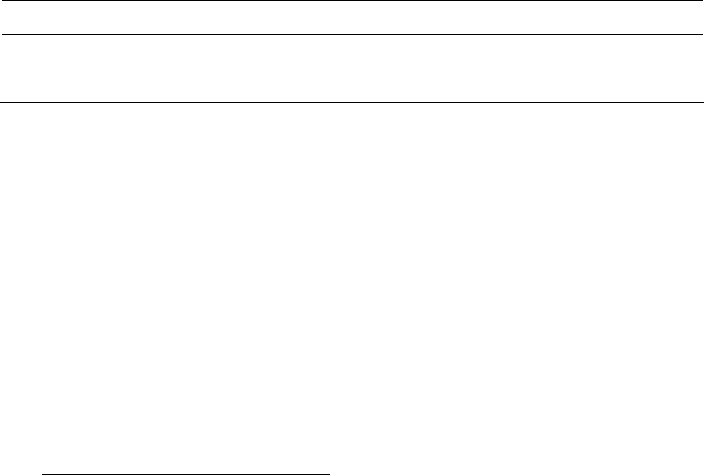

Figures of childbearing intensity have to be read together with the delay in the

timing of fertility that we have been observing since the 1955 birth cohort (Figure 7). In

the female cohorts born in the late 1960s, the mean age at first childbirth is almost 27

and the proportion of women with a first child before age 25 is declining with

subsequent birth cohorts owing to a sharp decline in early-age specific fertility rates by

cohort. Figure 8 clearly shows the decline in the level of fertility rates at ages 20 and

25. A steady progress of childbearing postponement is evident among the cohorts of the

mid-1950s and of the 1960s. Figure 9 depicts the differences in cumulated cohort

fertility, separately for first birth and second-order births, between women born in the

years 1960–1980 and women of the 1950 reference cohort. At age 30, Italian women

born in 1965 had on average .20 fewer first and second-order children than the 1950

cohort. The difference in fertility level with respect to the reference cohort widens for

younger women. At age 25, Italian women born in 1970 had .33 fewer first children,

and it is likely that this difference further widened as the cohort reached its late 20s.

The graphs also reveal the extent to which differences in fertility levels across cohorts

are due to fertility postponement (Billari and Kohler 2002). The Italian 1960 cohort

‘lagged’ behind the 1950 reference cohort and had on average about .13 fewer first

births at age 26. When this cohort reached the late 20s and early 30s, however, the gap

narrowed and fertility for first births partially recuperated; a similar pattern is observed

for second-order fertility.

Figure 7: Mean age at first child by birth cohort

23.5

24.0

24.5

25.0

25.5

26.0

26.5

27.0

1933 1937 1941 1945 1949 1953 1957 1961 1965

Source

: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

674 http://www.demographic-research.org

Figure 8: Age-specific fertility rates by cohort, 1940 –1980

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1988

Female birth cohort

Rates

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Source:

Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

The recovery in fertility after age 30 among cohorts born since the end of the

1960s helps to explain the slight increase in period fertility recently observed and also

suggests that a ‘new’ behaviour is emerging, characterised by childbearing

postponement and recuperation. In the near future, we do expect fertility to remain

under the replacement level. In addition, it will be very important to understand the

behaviours and intentions of the younger generations, namely those born in the late

1970s and early 1980s. Apparently their fertility is no longer declining compared to the

1975 cohort. They are succeeding in having at least one child and possibly two (Rosina

2004).

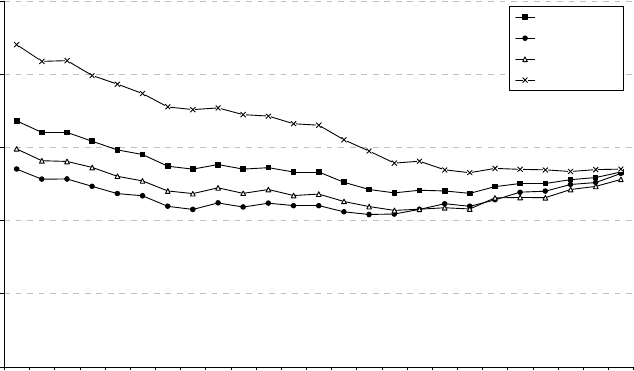

A further aspect that should be mentioned with regard to the alarming trends and

features of Italian fertility is its geographical heterogeneity. Differences in the level and

timing of fertility still exist among regions. In the Centre and in the North there are

higher levels of childlessness, more one-child families, and the highest mean age at

childbearing, but a certain stability in trends. In the South, there is a prevalence of two-

child families and a relatively higher proportion of numerous families (Barbagli et al.

2003). However, a deep convergence in fertility levels between the regions can be

observed in recent years (Figure 10). One can argue that the fast decline of the total

fertility level in the South will result in a further decline in fertility at the national level.

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 675

This is because the higher fertility in the South has, up to now, been ‘propping up’ the

national fertility.

Figure 9: Cumulated fertility by birth cohort

Comulative change in first birth progression rate by age and birth cohort

-400

-350

-300

-250

-200

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47

1950

1955

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

Comulative change in second birth progression rate by age and birth cohort

-300

-250

-200

-150

-100

-50

0

50

15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47

1950

1955

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

Source

: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

676 http://www.demographic-research.org

Figure 10: PTFR by geographic area , Italy, 1980-2004

0.00

0.50

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004

Italy

North

Centre

South-Islands

Source

: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

3. The proximate determinants of fertility

The decline of fertility has occurred without any radical change in family formation.

The majority of households are still formed by (married) couples with or without

children. Any other forms of ‘modern’ living arrangements were practically nonexistent

until the early 1990s due to the slow diffusion of informal unions, marital dissolution,

and subsequent step-family formation. Some incipient signs of change in household

distribution by typology can be observed in the very last decade (Table 4): The

percentage of childless singles and couples is increasing - also due, importantly, to

population ageing - as well as the share of informal unions of the total number of

couples and the percentage of step families after divorce. The most important change,

however, is the decline of marriage (Table 5). The number of marriages reached its

lowest level in 2003 (4.5 marriages per 1000 inhabitants). The first marriage rate per

1000 women younger than 50 years of age decreased from 1000 in 1961 to 580 in 2001,

while the mean age at first marriage reached 27.0 at the end of the 1990s. An interesting

trend is that the percentage of marriages celebrated by civil rite, quite insignificant until

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 677

the early 1970s, reached the value of 28.7% in 2003. The delay in marriage is related to

the behaviour of recent cohorts, and this is affected by delayed leaving of the parental

home and the consequent higher age at marriage compared to earlier generations

(Figure 11): The median age of leaving the parental home and that of marriage has been

increasing ever since the 1954-58 birth cohort, both for males and females.

Table 4: Households in Italy, 1994-2003

year Single

With 5

members

or more

Extended

households

Couples

with

children

C

ouples

w

ithout

children

Lone

mothers/

fathers

Informal

un

ions (out of

100 couples)

Step

Families

1994

–

1995 21.1 8.4 5.1 62.4

26.

7

10.9 1.8 4.1

1996

–

1997

20.8 7.9 5.3 61.2

27.

8

11.0 2.0 3.5

1998

–

1999

22.2 7.7 5.5 60.8

28.

1

11.1 2.4 3.9

2000

–

2001

23.9 7.1 5.1 60.2

27.

8

12.0 3.1 4.3

2002

–

2003

25.3 6.8 5.3 58.9

29.

2

11.9 3.9 4.8

Source

: Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

Table 5: Marriage indicators, Italy, 1961-2003

Year Number

Per 1000

inhabitants

% by

civil rite

First Marriage Rate

(women <50)

Mean age at female

first marriage

1961 397461 7.9 1.6 1000 24.7

1971 404464 7.5 3.9 1003 23.9

1981 316953 5.6 12.7 760 23.8

1991 312061 5.5 17.5 670 25.7

1993 302230 5.3 17.9 660 26.0

1995 290009 5.1 20.0 630 26.6

1997 277738 4.8 20.7 600 27.0

1999 280330 4.9 23.0 600 27.0

2001 264026 4.6 27.1 580

2003 257880 4.5 28.7

Source:

Our elaborations of ISTAT data.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

678 http://www.demographic-research.org

Figure 11: Median age at leaving parental home and marriage

by gender and cohorts

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

1944-48 1949-53 1954-58 1959-63 1964-68 1969-73

leaving home M

leaving home F

First marriage M

First marriage F

Source:

Barbagli et al, 2003.

Uncompleted Second Demographic Transition has been recalled as one of the

reasons why fertility is so low in Italy compared to Central and Northern European

countries, namely because non-marital fertility has not replaced the decline and delay in

marital fertility (De Sandre 2000). Although increasing, the share of births out of

wedlock is not higher than 14% and the great majority of children are still born to

married couples.

It can be argued that the Second Contraceptive Revolution (Leridon 1987) has yet

to take effect in Italy, which is another puzzling feature of the Italian paradox in family

behaviours. The very low fertility level has been reached by means of theoretically low-

effective contraceptive devices (Table 6). Until the end of the 1970s, 58% of married

women aged 18-44 relied on the method of coitus interruptus; in 1996 the same was

true for 34% of married women and 12% of singles, and, while the younger cohorts

increasingly rely on modern contraception, male-coitus-related methods - namely the

use of condoms and withdrawal - are still more popular than the pill, especially among

married and cohabitant couples (Dalla Zuanna et al. 2005). Notwithstanding, the

number of induced abortions, which was relatively high at the beginning of the fertility

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 679

transition, reaching 200,000 per year at the end of the 1970s, steadily declined in the

following 20 years, between 1983 and 2003 falling from 17.2 to 9.6 per 1000 married

women aged 15-49. In this period, all age-specific abortion rates declined, with the

exception of the fertility rate of women younger than 20 years of age, which is

relatively stable around 5-6%. In 2004, however, the gross rate of abortion slightly

increased (9.9 abortions per 1000 women at ages 15-49) mainly due to the foreign

immigrant population, which, on the whole, shows an abortion rate equal to 35.5 per

1000 (ISTAT 2006).

To conclude, instead of being responsible for the decline of fertility, Italian birth

control behaviour can be viewed as resulting from a lack of modernity, which, as we

discuss in the following sections, is viewed as a main cause of the current depressed

childbearing level.

Table 6: Women (%) by contraceptive method used (1979–1996)

Natural

methods Withdrawal Condom IUD Pill Others Total

Women’s

age

N, of

women

1979 married 9 58 13 4 13 3 100 18-44 4,493

1996 couples 6 34 25 9 24 2 100 20-49 1,750

1996 singles 2 12 32 3 51 1 100 20-49 558

Source:

Dalla Zuanna et al, 2005.

4. Explaining low fertility in Italy: micro and macro determinants

The determinants of fertility decline in Italy have been explored thoroughly (Ongaro

2002; Salvini 2004) and can easily be reconciled with the socio-economic and cultural

changes that occurred in Western industrialized countries after the Second World War.

Economic approaches

5

(Bernhardt 1993) as well as the cultural explanations

6

(Van de

Kaa 1987) are consistent with the empirical analysis of the individual life histories of

Italian women. In a recent paper (Kertzer et al. 2006), a comprehensive overview of the

most prominent explanations of low fertility in Italy and an analysis of panel

longitudinal survey data have been presented as parts of a project on Explaining Low

Fertility in Italy. The individual data analysis of the transition to first and second child

5

Economic approaches focus on increased female autonomy, the entry of an increasing number of women

into the labour force, and calculations of the direct and indirect costs of childbearing (Bernhardt 1993).

6

Cultural explanations, namely the diffusion of individualism and secularization, have been incorporated into

the Second Demographic Transition theory for a better understanding of the persistent decline of fertility and

its relationship with family changes (Van de Kaa 1987)

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

680 http://www.demographic-research.org

largely confirms that both the main factors chosen -- the economic approach (woman’s

labour-force participation) and the secularization one (married in a civil union) -- play a

significant and strong role in delaying or even discouraging women to have a (further)

child, with all the other characteristics controlled for. Also, the predictive meaning of

these two factors does not prevent the regional and cohort effects being meaningful.

Younger cohorts, namely women born between 1961 and 1970, have lower rates of

transition to a first and second child compared to earlier generations. Women living in

the South of Italy, i.e., those regions with a lower rate of female labour-force

participation and a lower percentage of civil marriages out of total unions, show a

higher risk of having children and shorter birth intervals than their counterparts of

Central Italy and the country’s North.

Once the two levels of observation – individuals and residential units – have been

integrated into a proper multilevel modelling framework (Bernardi and Gabrielli 2006),

the role played by women’s work and religiosity is confirmed at both levels: Being in a

religious marriage increases a woman’s propensity to enter motherhood and to have a

second birth earlier, while being employed depresses both transitions. The inclusion of

the contextual level variables does not modify the effect of individual characteristics,

but the regional random effects are statistically significant, indicating that the intercept

of the individual model varies over contexts. Also contextual factors have a significant

effect, though they impact on the timing of second birth and on first birth in different

ways: Living in a suburban or a non-urban area increases the probability to become a

parent but it has no effect on the second child; living in an area where female

employment is common considerably depresses the likelihood to become a mother and

to have a second child earlier. The level of religiosity has no effect on first birth, while

time-to-second-child is significantly shortened in contexts where attending Catholic

Mass is more widespread.

These results are in line with a previous multilevel analysis on total expected

fertility of Italian women aged 20-49 in the mid-1990s (Borra et al. 1999) based on a set

of micro variables (age, marital status, education, the number of siblings, employment

status of both partners, religious attendance, type of union) and three macro indicators

derived from a synthesis of macro variables through a principal components analysis

(1

st

component: degree of economic and social development, labelled as

‘modernisation’, 2

nd

: level of urbanisation, 3

rd

: secularisation). The individual variables’

effects were as expected. But much more interesting was the possibility to see the

contextual effects at the municipality level. As usual, those in the southern regions

(along with some regions of the North-East, such as Friuli Venezia Giulia) have a

context that raises fertility. The opposite applies to the northwest, some central regions

and in Sardinia.

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 681

However, these results do not help to explain the striking contradiction in the

relationship between very recent childbearing trends and macro-economic and cultural

differences observable at the regional level. Since one of the most notable features of

recent trends in Italian fertility is a tendency toward convergence of fertility rates

between the North and the South, this is not accompanied by any convergence in

women activity rates and in the spread of secularized behaviours. In a more detailed

analysis, some regional specificities emerge, such as the case of Basilicata, situated in

the South: In 2003, the total fertility rate stood at 1.20, i.e., it was below the national

average, but the female labour-force participation rate was among the lowest in Italy,

with only 46% of women aged 25-34 in the labour force, and only 9% of marriages

celebrated outside church (Kertzel et al. 2006).

Even more difficult to reconcile are results observed at the micro level as well as

the national lowest low level of fertility and low female labour-force participation rate

with the perception of Italy as one of the most traditional, Catholic, and family-oriented

countries among the Western societies.

Several studies have aimed to understand and to explain the particular position of

Italy in comparison to other European countries. De Rose and Racioppi (2001) found

that the analysis of the individual determinants of Voluntary Low Fertility (VLF: choice

of having 0 or 1 child at most) benefits integration with contextual conditions

influencing individual choices and the decision-making process. Women with

homogenous individual and family characteristics have different fertility expectations

based on their country of origin, just because their respective countries differ

demographically, socially, economically or culturally, as well as in terms of their

gender system. VLF decreases in those contexts where the welfare state is more

supportive to women and families and where there is a more balanced gender system.

Moreover, with a focus on Southern Europe, we compared Italy, Spain, Greece,

and Portugal, using a multivariate approach (De Rose and Racioppi 2004). The four

countries are similar in many respects – they have reached the lowest level of fertility

worldwide within a very short time; the marriage rates have decreased, divorces and

cohabitations are not yet common, but there are differences in socio-economic

indicators. From this analysis we conclude that Southern Europe has a homogeneous

demographic system but is relatively heterogeneous with regard to other societal

characteristics. Yet, the closeness between Italy and Spain with respect to socio-

economic and cultural variables that affect sexual, family, and reproductive behaviours

(e.g., the strong association between age at first sexual intercourse and religious

attendance) becomes clear.

As an important source of variability among countries, the different level of

institutional support to family and fertility is usually examined. Accordingly, fertility is

expected to be higher in those countries where the government offers programs that

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

682 http://www.demographic-research.org

make women’s work and childbearing more compatible (Rindfuss et al. 2003). Again,

the case of Italy appears as contradictory. The provision of publicly funded childcare,

maternity leave, and tax benefits are all better in Italy than what is available in the USA

or UK, yet there the level of fertility is significantly higher. Not surprisingly,

Engelhardt and Prskawetz (2004), looking at trends in OECD countries over time,

conclude: “Trends in the variables that would be representative for the role

incompatibility hypothesis and the ease in combining work and child-rearing…cannot

be related to the trends in fertility.”

In conclusion, all of these factors, though playing an important role in the

explanation of the decline in Italian fertility, are not sufficient to understand its

persistence at such a low level. Many scholars are exploring different paths of research

that, on the whole, support the fundamental idea that the peculiar interaction between

economic and structural changes and the nature of family ties in Italy leads to a

different development of fertility and household dynamics with respect to those

included in the Second Demographic Transition (Billari and Wilson 2001; Micheli

2004). In the following, we argue that the substantial delay (or even failure) with which

society has adapted to changes in individual attitudes and behaviours and in the quality

of the relationships between genders and among generations is forcing men and women

toward a very low fertility level.

5. Societal conditions impacting fertility and family

What is peculiar in Italy is the speed with which post-war social and economic changes

have taken place, namely concerning the growth of the service sector, rising female

employment, and the increase in the level of education. The change has been very fast

(within two or three decades), but the social structure has remained static in many

respects as regards the organisation of the family, the school system, and women’s time

schedule of work.

“

In the last 40 years, Italian families have changed: the typical

middle-class family with the husband as breadwinner and the wife totally devoted to the

home, with a clear separation of the social tasks of the spouses, has quickly vanished

(…). Italian society has been more reluctant than elsewhere to adapt to the pressures of

economic and cultural change.” (Dalla Zuanna 2004). This is a fundamental key to

understanding why the level of fertility remains so low and why no clear sign of a

reverse trend is yet observed, despite the fact that the ideal number of children is always

definitely higher than effective fertility. The 1996 Fertility and Family Survey shows an

almost entirely generalised desire to have children: 98% of the 20–29-year-olds

interviewed declared that they wanted children. On average, the desired number of

children is 2.1 and the desire to have children remains unaltered even in more recent

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 683

generations and even for women who have made large investments into their education

and want to achieve their career aspirations.

Many distinctive interrelated aspects need to be discussed when refering to the

‘failed societal adaptation’.

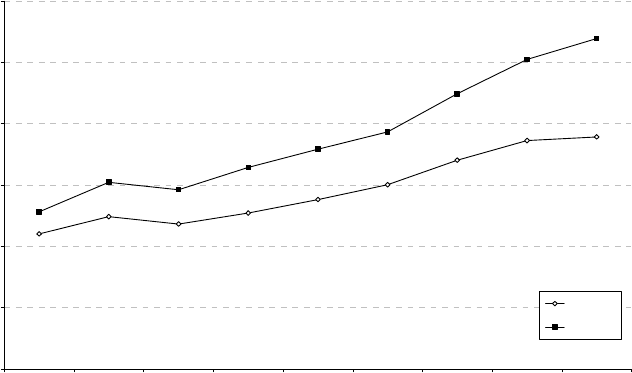

5.1 Lack of labour market flexibility

Women and young people face an inflexible labour market and, in an adult male

dominated society, adjustments have been taking place very slowly and reluctantly,

despite greater investment in human capital through enrolment in education. The data in

Table 7 show an increase in the proportion of people aged 15 or above with a university

or a higher-secondary degree, both comparing younger versus older ages and comparing

women versus men. Moreover, if one compares trends of the number of university

graduates per 100 individuals above age 25 by gender (Figure 12), it is evident that

women obtained better results than their male counterparts and that the gap is

increasing among the younger student cohorts.

Table 7: Population aged 15 and over by educational level, age and gender,

2004 (percentage composition by gender)

Age

groups

University doctorate,

degree and diploma

Senior secondary

school certificate

Vocational

qualification

Junior secondary

school certificate

Primary school

certificate

Males

Females

Males

Females

Males

Females

Males

Females

Males

Females

25

–

29

11.3

16.4

46.1

49.3

6.3

5.4

32.6

25.7

3.7

3.2

30

–

34 13.0

18.4

36.4

39.1

6.8

7.0

39.3

31.4

4.5

4.1

35

–

39 11.8

14.2

32.2

34.5

7.8

8.8

42.0

36.5

6.2

6.0

40

–

44 11.3

11.5

30.1

30.9

7.0

9.1

44.5

39.0

7.1

9.6

45

–

49 11.0

11.2

30.9

25.9

6.9

9.1

38.5

34.4

12.6

19.3

50

–

54 11.5

10.4

25.1

19.7

6.5

6.7

35.4

30.2

21.5

33.0

55

–

59 9.7

7.7

21.3

14.6

5.6

5.0

29.8

23.3

33.6

49.4

60

–

64 7.9

4.4

17.3

11.5

3.5

3.5

24.8

19.1

46.4

61.5

65+ 5.5

2.2

9.8

6.3

1.9

1.7

17.0

11.2

65.7

78.7

Total 8.7

8.4

27.3

25.1

5.4

5.3

35.3

27.9

23.3

33.3

Source: ISTAT, Labour Force Survey, 2004.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

684 http://www.demographic-research.org

Figure 12: University graduates per 100 individuals age 25 and over

by gender and school year

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

1995-1996 1996-1997 1997-1998 1998-1999 1999-2000 2000-2001 2001-2002 2002-2003 2003-2004

Percent

Males

Females

Source: ISTAT, Labour Force Survey, 2004.

Nevertheless, the labour market is more favourable to men than it is to women,

even among university graduates. In fact, whatever the educational level, the

employment rate is higher for men than it is for women (Table 8). Employment rates for

Italy, including a comparison with the EU, show a persistent disadvantage of Italian

women and a high level of unemployment among young people. The figures in Table 9

highlight the peculiarity of the Italian employment system: Compared to the average of

European men, Italian employment rates are higher in the middle age groups and much

lower in the young and in the elderly age groups; the gender gap in Italy is

comparatively higher than in all European Union countries, especially for younger and

older age groups. The disadvantage of women is documented also by professional

segregation (Table 10). Women who work ‘at the top’ as managers or politicians

constitute a minority and they are highly underrepresented in that category, while they

prevail in the executive categories of the tertiary sector. Gender inequalities in income

are also documented. Women earn 30% less than men on average and the gender gap is

significant also when controlling for job characteristics, though decreasing by level of

qualification (Addis 2006; OD&M 2006). However, this does not discourage young

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 685

women who, instead of staying home and dedicating themselves to childbearing, prefer

to invest in education and professional training; this leads to a further delay in family

formation. Employed women, especially those married and with children, face a very

rigid working-life organisation, mainly with regard to time schedules of work, making

it difficult for many of them to reconcile work activities with family life. Despite a

relatively generous maternity leave programme (see below), many working women

complain about the lack of flexibility in time organisation (ISTAT 2004). Not

surprisingly, then, among working mothers the activity rate of those aged 25-34 and 35-

44 steadily decreases with the number of children, while no such change is observed for

men (Table 11). One form of flexibility, namely part-time work options, has been

introduced recently. Italian workers, however, both male and female, take advantage of

this opportunity to a lesser degree than the rest of the EU (Table 12). In countries such

as Italy, where the option of part-time work is still very limited, its effect on fertility

may be ambiguous. The results of a recent comparative study (Del Boca et al. 2004)

using European Community Household Panel data (ECHP) show that, when controlling

for all personal, family, and available environmental contexts, Italian women still work

significantly less than women in France and the UK. If Italian women had access to the

same number of part-time positions as women in the UK, their participation would

increase by 52.5% and the fertility rates would decrease by 2.8%. In a country where

part-time work is rare, married women are forced to choose between not working and

working full-time. The growing availability of a third option would change the

available set of choices: If unemployed women chose to work part-time, their fertility

rates might decline. By contrast, if full-time working women chose to reduce their

working schedule, their fertility might increase. The net effect on fertility depends on

the magnitude of these different flows.

Women, however, look at part-time employment as an important resource to

reconcile work activity with the family (Del Boca 2002). In 2003, around 70% of part-

time working mothers declared to have chosen this form of employment in order to be

in a better position to take care of their children.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

686 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 8: Employment rates by educational level and gender, 2004

Educational level

Males

Females

Primary school 25.6

8.0

Junior secondary school 61.0

33.3

Vocational qualification 76.7

55.9

High school 69.4

53.7

University 78.4

70.6

Total 57.4

34.3

Source: ISTAT, Labour Force Survey, 2004.

Table 9: Employment rates by gender and age in Italy and EU, 2002

EU Italy

Age groups

Males Females Total Males Females Total

15

–

19 25.7 21.2 23.5 11.6 6.9 9.3

20–24

61.0 52.1 56.6 46.7 33.4 40.0

25

–

29 80.9 67.2 74.1 71.6 52.1 61.9

30

–

34 88.4 68.3 78.5 86.5 58.3 72.5

35

–

39 89.9 68.8 79.4 91.5 58.4 75.1

40

–

44 89.5 70.3 80.0 91.8 57.0 74.5

45

–

49 88.4 68.6 78.5 91.5 54.0 72.7

50

–

54 83.0 60.4 71.6 81.3 42.4 61.7

55

–

59 66.0 43.9 54.8 53.1 26.3 39.4

60

–

64 32.8 16.3 24.3 29.3 8.1 18.3

65+ 5.5 2.1 3.5 6.1 1.3 3.3

Source

: ISTAT, Ministero per le Pari Opportunità (2004)- "Come cambia la vita delle donne", Eurostat, Labour Force Survey.

Table 10: Professional composition of employed men and women, 2004

Professions Absolute numbers (in thousands)

Males Females Total

Members of legislative bodies, managers & entrepreneurs 808 255 1063

Intellectual, scientific & highly specialized professions 1238 1023 2261

Intermediate professions technical experts 2335 2057 4392

Administrative & management executives 1038 1493 2531

Sales and household services 1637 1883 3520

Craftsmen, skilled workers & farmers 3597 672 4269

Plant & machinery operators, industrial assembly-line workers 1651 398 2049

Non-skilled workers 1064 997 2061

Armed Forces 253 5 258

Total (in thousands) 13622 8783 22405

Source

: Labour Force Survey 2004 (ISTAT,2006).

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 687

Table 11: Employment rates of parents aged 25-64 by number of children,

gender and age, average 2004 (percentage values)

Males Females

Number of children

25–34

35–44

45–54

55–64

25–34

35–44

45–54

55–64

One child 92.8

94.9

88.3

43.3

55.1

66.3

52.0

19.8

Two children 90.9

94.1

89.9

52.6

38.9

54.4

50.6

25.0

Three children 84.6

90.7

87.5

55.5

25.9

37.5

40.0

23.3

Total 91.8

94.0

88.9

47.9

46.7

55.5

49.6

21.6

Source:

Elaboration on ISTAT data (Labour Force Survey 2004).

Table 12: Percentage of part-time employed in Italy and in the EU

by age groups and gender, 2002

Italy EU

Age groups

Males Females Males Females

25–34 4.2 17.5 4.

7

26.7

35–44 2.5 19.8 3.

4

36.8

45–54 2.7 13.5 3.

8

33.6

55–64 3.5 16.7 6.

0

33.1

Source:

ISTAT, Ministero per le Pari Opportunità (2004)- "Come cambia la vita delle donne".

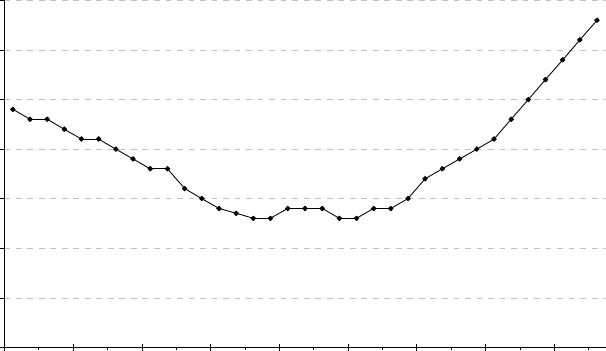

5.2 An unbalanced gender system

Women have to cope with an unbalanced gender system in the family. Combining work

activities with childbearing and other family duties, including taking care of elderly

relatives, is entirely left to women’s adaptability. McDonald (2000) suggested that

fertility has fallen especially in societies and social groups where the public gender

system has evolved evenly, while the private gender system (i.e. of the couple) has

remained attached to more traditional asymmetries. In Italy, too, during the last 40

years, the public gender system changed in an even sense: Women now have access to

any profession, they achieve a higher educational level than men, and, when employed,

they work almost as hard as men, especially before entering motherhood. At the same

time, however, the couple’s sharing of housework is heavily unbalanced – not only

when the woman is a housewife (in the traditional logic of ‘job sharing’), but even

when she works full-time. Women need to and want to work in order to avoid an

income reduction as well as a loss of role and identity. At the same time, spending long

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

688 http://www.demographic-research.org

hours on household chores, without any significant help from the husband, contributes

to making low fertility more than a choice.

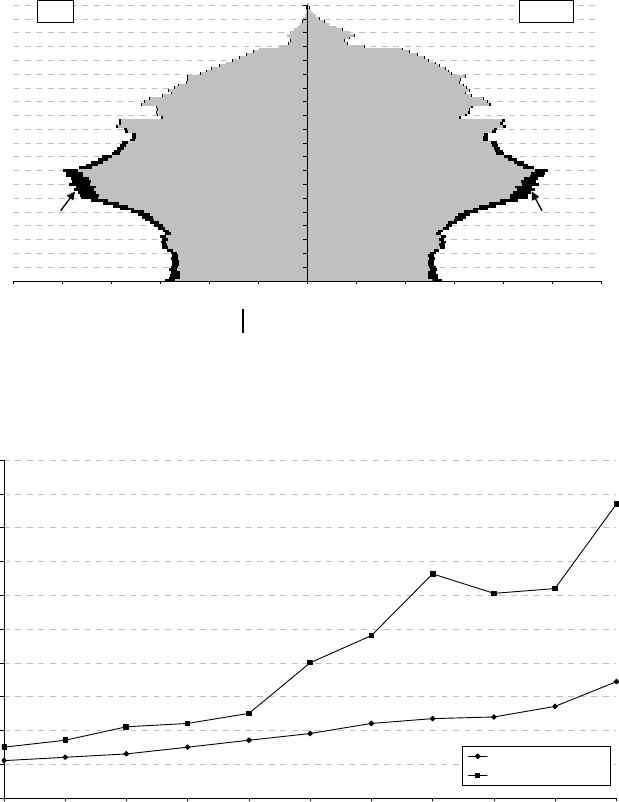

The very low percentage (14%) of employed fathers out of the total number of

parents taking parental leave is a good indicator of the low engagement of male partners

in family duties. Moreover, the percentage of exits from the labour market due to family

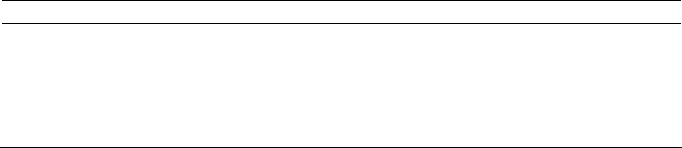

issues is greatly differentiated by gender (Figure 13). Over 60% of women but less than

20% of men do so at ages 40-44. The youngest male cohorts appear to be more

available to take care of their children and 52% of them declare to be interested in

taking parental leave, provided that their employer allows them to do so.

Figure 13: Exit from labour market because of family duties

by gender and age, 2001-02

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-W

Percent

Males

Females

Source

: Centra M. (2003), Modelli di mobilità: ciclo vitale e partecipazione al mercato del lavoro in Battistoni L, Op, Cit.

A low level of fathers’ involvement in child care is another distinctive feature of

the Italian gender system. No more than 25% of fathers of children less than 5 years of

age are involved in the care of them. Again, the younger couples (i.e. unions formed in

the 1990s) appear to be more egalitarian, with the respective male partners being much

more collaborative (ISTAT 2005). Using Fertility and Family Surveys data in different

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 689

countries, including Italy, Pinnelli and Di Giulio (2003) estimated that couples with

relatively small gender differences with respect to age, education, and work

involvement have the highest fertility. At the individual level, the fact that a married

working woman receives some help from the husband when looking after their children

or performing household chores has some significant and positive impacts on the risk

and timing of second or third births (Mencarini and Tanturri 2004; Cooke 2003) and

also affects her fertility intentions (Pinnelli and Fiori 2006).

5.3 The ‘delay syndrome’

Another distinctive feature of the Italian situation is the rigidity with which individual

and contextual factors affect the various stages of the life cycle: end of education, entry

into the labour market, exit from the family, entry into union, and formation of an

independent household. Closely related to this rigidity, and simultaneously a cause and

an effect, are the ‘costs’ of leaving the parental home. Of 100 young people aged 18-34,

the fraction of those living in the parental home increased between 1993 and 2003, both

for males and females, from 62.8% to 66.3% and from 48% to 52.9%, respectively.

Various explanations have been given, such as the high cost of housing and young adult

unemployment (Saraceno 2000). None of these are convincing, because also the

fraction of young Italian adults living with parents and in full-time employment is

rising, from 47.7% to 53.4% among males and from 34.2% to 37.4% among females

(Table 13). Moreover, young adults admit that they like to live in the parental home,

where they typically pay almost nothing for their upkeep, have their mother doing all

their cooking and washing, and can spend money on cars, vacations, and discos instead

(Sgritta 2001; Palomba 2001).

Compared to other countries, young people in Italy do not show any of the

flexibilities of young people in other European countries when they leave the family

home to go and live on their own, to study, to work, and above all to live with their

partner and have children (Billari and Rosina 2004). The delay in forming a family at a

relatively late age may lead, for various reasons, to not having children at all or to

reduced fertility due to being strongly accustomed to a certain lifestyle (Livi Bacci and

Salvini 2000).

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

690 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 13: Young people (18-34) not in union, living with their parents,

by gender and condition

Year Employed Searching for a job Housewife

(1)

Student

Other

Male

1993 47.7 22.1 - 25.3

4.9

2003 53.4 16.3 - 26.1

4.2

Female

1993 34.2 22.4 6.0 36.0

1.4

2003 37.4 19.1 2.5 39.3

1.8

Source:

Indagine multiscopo sulle famiglie “Aspetti della vita quotidiana” Year 2000, ISTAT 2005.

(1) This includes not active young people caring after the house.

5.4 Too much family

The last social collective process which, we believe, helps to maintain the gap between

desired and actual fertility in Italy is the persistence of strong ties between parents and

children. Parents invest a lot in their (only) child and a very high cost-value is attributed

to these children, which in Italy is shouldered entirely by the family. Not having a

second or third child seems to be resulting from the fear of lowering the child’s quality

of life, who is highly protected by its parents. Moreover, as the children’s prospects of

social mobility have been low or nonexistent for a long time, Italian families show little

enthusiasm to push their children ‘out of the family nest’. In Italy, proximity parameters

between children and parents are strong: Young adults leave home later and later and,

when they go, they often reside nearby, and visits between parents and children are very

frequent (Dalla Zuanna 2004). The persistent proximity between parents and children

favours intense exchanges of all kinds between the generations: Parents support

children until they leave the parental home and help them financially in buying a flat or

a house and in organising the very expensive (religious) marriage ceremony; they also

are expected to become good grandparents; children in turn will ensure emotional and

material sustenance for their parents when they become elderly.

The consequence of these factors is that young people in general seem to live in a

context that is characterised by strong family ties, and it does not favour independent

life choices. This may also help to explain why the welfare system is ungenerous with

families that have children: In a society centred on family ties, there is little room for

the state. A very instructive example is the use of childcare services. In Italy, the vast

majority of children aged 3-5 attend nursery school, a proportion as high as, or higher

than, that found in many other European countries with higher female labour-force

participation rates. However, according to ISTAT data collected in 1998, only 8% of

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 691

Italian children aged 0-2 went to public day care and, in 2002, 56% of all women then

in the work force who had given birth between July 2000 and June 2001 had their

babies cared for by the babies’ grandparents while they were out to work. Thus, the lack

of public services offering child care is partly due to a low demand for these services

owing to a strong cultural bias against the practice to send the smallest children outside

the home.

Families tend to solve their tensions by themselves; therefore, institutions are not

particularly pressed to intervene. Given this strong orientation towards the ‘private

value’ of children, it is difficult to recognize their ‘collective value’ (Livi Bacci 2001).

5.5 Too much Church and too little religiosity

The causal link between Catholicism and marital and reproductive behaviour is not easy

to establish. On the one hand, is the function of the Church in public life as a cultural

and political institution; on the other, the influence of religious feelings and the set of

values on private affairs. Despite the large influence on public life exerted by the

Catholic Church through the dominant political party, the Democrazia Cristiana,

through the end of the 1980s, many liberal laws were approved by a large and diverse

parliamentary majority during the 1970s: a divorce law in 1970, a law passed in 1971

permitting contraceptive advertising, a reform of norms regulating family relationships

in 1975, and a law legalising abortion in 1978. In many cases, the political battles were

very hard.

During the 1990s, Democrazia Cristiana was swept away by corruption scandals;

other minor Catholic parties were founded on the left and right of the political spectrum

but their political power cannot be compared to that of the previous period.

Nevertheless, the influence of the Catholic Church on public issues is still notable. For

example, a law on medically-assisted reproduction approved by the Italian Parliament

in 2003 contains significant restrictions based on Catholic principles: The intervention

is permitted only for married couples without resorting to any outside sperm or ovule

donors. Also, the current discussion on the legal status of informal unions is strongly

influenced by the Catholic parties. In general, public life and the institutional setting are

constantly influenced by the Catholic ethical viewpoint.

The same contradiction is evident when we look at individual behaviour. In the

mid-1990s, 97% of people aged 18 and older declared themselves to have been baptized

into the Catholic Church; however, no more than half of them regularly participated in

religious rites. The participation is even lower among young people, especially men

(Table 14). As far as family life is concerned, Italian people are far from following the

prescriptions of the Church, neither on sexual and contraceptive behaviour (as

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

692 http://www.demographic-research.org

mentioned above) nor on spousal behaviour. Separation and divorce are continuously

increasing as well as informal unions, especially among the youngest generations.

Similarly with respect to fertility: Expectations and ideals are influenced by religious

principles, but actual choices and behaviours are impacted much less so (Dalla Zuanna

2004). The persistent influence of the Church at a political level contributes to delays in

the spreading of modern behaviours, which might lead to an institutional and cultural

context favourable to childbearing.

Table 14: Persons aged 6 and over by frequency of attendance at a

place of worship and by age and gender (per 100 persons

of the same age and sex) - Year 2003

Once a week (at least)

Never

Age group

Male

Female

Male

Female

6–13 59.5

63.8

7.7

5.7

14–17 30.9

43.9

15.3

12.3

18–19 19.3

29.7

23.5

13.5

20–24 13.7

25.7

27.3

16.8

25–34 16.3

27.8

23.3

15.0

35–44 18.9

33.5

21.0

12.2

45–54 21.9

41.3

19.2

9.8

55–59 25.1

48.2

17.9

7.9

60–64 32.0

55.0

15.6

7.2

65–74 38.3

59.8

15.6

7.4

75 + 36.8

48.7

21.4

19.0

Total 27.1

42.9

19.0

11.6

Source:

Indagine multiscopo sulle famiglie “Aspetti della vita quotidiana” Year 2003, ISTAT 2005.

6. Family policies

Fertility trends have been clear for a number of years and demographers have tried to

draw attention to them. However, public concern for policy reform is very recent, and

strongly related to the fear of the consequences of low fertility, namely the crisis of the

pension system and in the context of growing foreign immigration.

The two preceding governments (1996-2001; 2001-2006) and the present one have

directly addressed this question, but the overall context is still unfavourable in terms of

persuading women and men to have the number of children consistent with their desires

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 693

and ideals. First, compared to other European countries public transfers to families and

children are not generous. Second, the societal context in which children are raised is

not child-friendly in terms of time use, mobility, and public spaces. Third, the need of

women and mothers (and fathers) to reconcile their activities inside and outside the

family is largely unmet. Fourth, the late transition to adulthood in Italy heavily depends

on the functioning of the education system, that of the labour market, and housing

arrangements.

A brief description of the main measures currently effective follows.

6.1 Financial support

6.1.1 Indirect financial support

Working people are allowed fiscal deductions for both children and other dependent

relatives, including the no-income marital partner; until 1998, the rate of deduction was

higher for the spouse (namely the wife) than for children, thus discouraging married

women from entering the labour market. Since 1998, the rate of deduction for children

has been substantially increased, matching the level for spouses.

6.1.2 Direct financial support

There is no generalized form of income transfer to the family. All transfers are linked to

the family and the individual’s income.

Family allowance, is granted only to employed, unemployed, and retired people

with very low income; the amount depends on the number of family members and the

family situation (it is higher for a single-parent family or for a family member with a

handicap).

Maternity allowance of 250 Euro per month for 5 months, established in 1999,

which is given to the mother whose family income is relatively low (lower than 25,800

Euros annually). It is now given also to foreign women.

Family allowance for three or more children, is 103 Euro per month granted to

large families with an income close to the poverty threshold.

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

694 http://www.demographic-research.org

6.2 Social policies favourable to work-family reconciliation

6.2.1 Maternal leave

Maternal leave is compulsory and lasts 5 months, to be taken prior to or after delivery,

depending on the woman’s choice. In exceptional cases, it can be granted to the father

instead of the mother. The woman has the right to maintain her job and she receives no

less than 80% of her salary (paid by social security). This measure was introduced in

1971 only for employed women; in 1987 it was extended to self-employed women and

in 1990 to highly skilled professionals (lawyers, medical doctors, architects; etc.); more

recently it was extended also for women with a temporary job.

6.2.2 Parental leave

According to a recent law (8 March 2000 n. 53), parental leave is voluntary and

provides the right for fathers as well as mothers to stay home for 6 months each until

the child reaches the age of 8; the job is preserved and they receive 30% of the salary

(80%-100% if they work in the public sector). Law no. 53 provides the father with the

legal right by choice to take care of his child, even when his spouse (or partner) is a

housewife or is self-employed. Employers receive some fiscal benefits if parental leave

(especially for male employees) is not discouraged. Some positive effects of this law on

fathers’ participation in childcare have already been observed.

6.3 Flexibility of the labour market

Both the law mentioned above and the more comprehensive law on work flexibility,

passed in 2003, introduced many fiscal and monetary incentives to employers who

allow for some forms of flexibility such as part-time employment, flexible working

hours, shift work, job sharing, and remote work. These possibilities have not been

proposed to directly affect childbearing but they could be family friendly, if used not

only in the employers’ interest, but also in the interest of workers and their family.

6.4 Child care services

As observed above, social service provisions for families with young children are

largely insufficient. There are very few kindergartens for infants aged 0-2 (in 2000,

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 695

only 7.4% of children aged 0-2 attended kindergartens, and attendance concentrated

mostly in the northern-central regions). In 2002, the government approved and partially

financed a number of projects for kindergartners in many private workplaces. The

service is fee-paying, and the charge depends on parental income. In larger cities, such

as Rome, the kindergarten calendar starts on 1

September and ends on 30 June, offering

a full day of service, from 7:00 to 18:00.

The supply of private and public schools for children aged 3-5 is much broader. In

the school year 2000-01, 100% of children aged 3-5 attended school. The organisational

model of the public childcare schools may vary from town to town and, partly, from

school to school. The service is free of charge; a contribution can be required for the

school canteen and transport. The opening date is established by the regional school

calendar and the closing date is usually 30 June. In the larger cities, parents can choose

between two timetables: morning classes — from Monday to Friday, 8:00 - 13:20 —

and full time classes — from Monday to Friday, 8:00 - 17:00.

6.5 Policies of the present and recent past concerning population and family

The poor development of family policies in Italy captured by the Mediterranean Model

– whose features have been depicted in the present chapter – can be explained by

historical, political, and ideological reasons:

A very long tradition of strong family ties, weak public institutions, and territorial

differences;

A family model with traditional and patriarchal relationships some of which

continue to this day;

The experience of fascism: For the first and only time in Italy, during the 1930s

and early 1940s, explicit demographic and family policies were pursued to increase the

birth rate, to strengthen the authority of the ‘husband – father’, and to subordinate the

family to the political objectives and to the principles of the regime;

The strong belief (only recently weakened due to awareness-raising campaigns of

demographers) that Italy was already over-populated and that therefore a policy aimed

at an elevated birth rate was not needed.

The lack of an explicit family policy in Republican and democratic Italy ever since

the war can be partly explained by citing the fascist heritage and the need to distance

oneself from its demographic policy objectives. Moreover, it is worth adding the post-

war conflict concerning family values among the political and cultural forces that has

been lasting to date (Saraceno 2003), with the Catholic Church and the Catholic-

inspired party, Democrazia Cristiana, aiming at protecting the unity of the family on

the one side; and the Marxist-inspired political forces (Communist and Socialist Parties)

De Rose, Racioppi & Zanatta: Italy: Delayed adaptation of social institutions to changes in family behaviour

696 http://www.demographic-research.org

and the anti-clerical-liberal-oriented forces aiming at promoting individual freedom and

rights (radical and liberal parties) on the other.

Moreover, one should take into account that until the 1960s, many services for

children and the elderly were directly or indirectly managed by the Catholic Church,

which sought to keep control over this field, thus hampering the development of public

services.

However, in the 1970s, there was a brief period when public social services for

women and families were being developed. This was the period of rising female

employment, of the feminist movement, of some local left wing administrations, of the

left-centre wing governments. In the late 1970s, the Catholic Party and the Communist

Party briefly compromised on some issues (the so-called ‘historical compromise’).

During this period, the state nursery schools for 3-5 -year- olds was instituted (1969),

together with the municipal kindergartens for children up to 3 years of age (1971).

Other important issues of this period were measures concerning compulsory and

optional maternal leave for employed women (1971), the divorce law (1970), the new

family legislation (1975) establishing legal equality between husband and wife and

between legitimate and extra-marital children, the institution of family-planning

services (1975), a law on equal gender opportunities in the workplace, which to a

certain extent allows even fathers to receive optional leave (1977), a law introducing the

legalization of abortion (1978); and the institution of the national health system (1978).

With these measures, the period of expanding public services in Italy came to an

end. In the 1980s, the crisis of the Welfare State began, a financial and structural crisis

that continues to date.

6.6 A short overview of the major political parties’ position on fertility issues and

policies

The policymakers’ awareness of the importance of policies supporting families,

especially those with children, is relatively recent and dates back to the second half of

the 1980s. Only in this period did political parties start considering enacting laws to

deal with family behaviour. Such laws would also aim at supporting fertility, but

through different modalities and tools, according to the different ideological trends.

To sum up, we can highlight four main objectives:

a) supporting families through social services, mainly aimed at children and the

elderly;

b) supporting reconciliation between family and working commitments and supporting

gender equality;

c) an opposition to abortion, and support of maternity;

Demographic Research: Volume 19, Article 19

http://www.demographic-research.org 697

d) the reform of the family tax system, aimed at reducing taxes for families with

children.

The first two objectives have been promoted by left-wing parties and left-wing

local administrations; the remainder have been advanced by the Democrazia Cristiana

and by right-wing parties, e.g., the Italian Social Movement (MSI), according to the

various declarations made by the political parties on family issues.

During the electoral campaigns of 1994, 1996 and 2001, family policies gained

importance in the programmes of the party coalition (left-centre camp and right-centre

camp) and the issue of supporting fertility assumed higher prominence in both camps.

In these years, family support was one of the main issues in the political debate.

According to the right-centre camp to be achieved by financial help and reduced taxes

for families with children. The left-centre camp demanded financial support for families

as well as the introduction of measures aimed at reconciling family with working

commitments, such as a wider application of parental leave (following a European

Union regulation issued in 1996) and the development of services for children.

Another topic of interest was the recognition of unmarried heterosexual and

homosexual couples, strongly opposed by the right-centre parties. The left-centre

coalition widely agrees on the need of these unions to be recognized, even if a

distinction between heterosexual unions and homosexual unions is highly

recommended.