'/6@+1*$3/:+67/8<'/6@+1*$3/:+67/8<

/-/8'1422437'/6@+1*/-/8'1422437'/6@+1*

97/3+77')918< 9(1/)'8/437 .'61+741'3").4414,97/3+77

"4)/'1386+56+3+967./5#.+!41+4,378/898/437"4)/'1386+56+3+967./5#.+!41+4,378/898/437

90+7."9*

'/6@+1*$3/:+67/8<

279*,'/6@+1*+*9

6'/-%%'3"'3*8

2'3*''9-497

4114;8./7'3*'**/8/43'1;4607'8.8857*/-/8'1)422437,'/6@+1*+*9(97/3+77,')918<59(7

45<6/-.8"56/3-+6%+61'-

#.+46/-/3'159(1/)'8/43/7':'/1'(1+'8.885;;;756/3-+61/30)42)438+38

9

++6!+:/+;+* ++6!+:/+;+*

!+547/846</8'8/43!+547/846</8'8/43

"9*90+7.%'3"'3*86'/-%'3*'9-4972'3*'"4)/'1386+56+3+967./5#.+!41+4,

378/898/437

97/3+77')918< 9(1/)'8/437

.8857*/-/8'1)422437,'/6@+1*+*9(97/3+77,')918<59(7

9(1/7.+*/8'8/43

"9*90+7.%'3"'3*86'/-%'9-4972'3*'>"4)/'1386+56+3+967./5#.+!41+4,378/898/437?

4963'14,97/3+778./)7"9551+2+38557

#./7/8+2.'7(++3'))+58+*,46/3)197/43/3/-/8'1422437'/6@+1*(<'3'98.46/=+*'*2/3/786'8464,

/-/8'1422437'/6@+1*8/7(649-.884<49(</-/8'1422437'/6@+1*;/8.5+62/77/43,6428.+6/-.87

.41*+67'3*/75648+)8+*(<)45<6/-.8'3*466+1'8+*6/-.87&49'6+,6++8497+8./7/8+2/3'3<;'<8.'8/7&49'6+,6++8497+8./7/8+2/3'3<;'<8.'8/7

5+62/88+*(<8.+)45<6/-.8'3*6+1'8+*6/-.871+-/71'8/438.'8'551/+784<49697+4648.+697+7<493++*844(8'/35+62/88+*(<8.+)45<6/-.8'3*6+1'8+*6/-.871+-/71'8/438.'8'551/+784<49697+4648.+697+7<493++*844(8'/3

5+62/77/43,6428.+6/-.87.41*+67*/6+)81<931+77'**/8/43'16/-.87'6+/3*/)'8+*(<'6+'8/:+4224371/)+37+5+62/77/43,6428.+6/-.87.41*+67*/6+)81<931+77'**/8/43'16/-.87'6+/3*/)'8+*(<'6+'8/:+4224371/)+37+

/38.+6+)46*'3*46438.+;460/87+1,/38.+6+)46*'3*46438.+;460/87+1,46246+/3,462'8/4351+'7+)438')8*/-/8'1)422437,'/6@+1*+*9

1

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: THE ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS

Mukesh Sud

Augustana College

639 38

th

Street

Rock Island, IL 61201-2296

p 309-794-7399

f 309-794-7605

Craig V. VanSandt

Augustana College

639 38th Street

Rock Island, IL 61201-2296

p 309-794-7334

f 309-794-7605

Amanda M. Baugous

Augustana College

639 38th Street

Rock Island, IL 61201-2296

p 309-794-7340

f 309-794-7605

2

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: THE ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS

Mukesh Sud – Dr. Sud is currently an Assistant Professor of Management at Augustana College

in Rock Island, Illinois. An engineer by profession, he has been an entrepreneur in the Thermal

Spraying field. After exiting from his business he completed a Ph.D. in 2006, from the Indian

Institute of Management, Bangalore. Dr. Sud’s doctoral work has been in the field of corporate

entrepreneurship and emerging markets. Besides social entrepreneurship his research has focused

on the impact of failure both at the individual and firm level. Dr. Sud has published papers in the

Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal and IIMB Management Review.

Craig V. VanSandt – Dr. VanSandt obtained his Ph.D. from Virginia Tech, and is currently an

Associate Professor of Management at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. He has

authored papers that have appeared in Law & Policy, Business and Society, Journal of Business

Ethics, International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, Journal of Management

Education, and a book chapter in Systematic Occupational Health and Safety Management. Dr.

VanSandt’s research interests include organizational climate’s effect on employee behavior, the

role of business in society, and ethical issues of corporate governance.

Amanda M. Baugous – Dr. Baugous obtained her Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational

Psychology from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and is currently an Assistant Professor

of Management at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. She has authored papers that have

been presented at Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Industrial/

Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, and North American Management

Society conferences. Dr. Baugous’s research and consulting interests include the design,

evaluation, and implementation of employee selection and performance management systems.

3

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: THE ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS

ABSTRACT

A relatively small segment of business, known as social entrepreneurship (SE), is

increasingly being acknowledged as an effective source of solutions for a variety of social

problems. Because society tends to view “new” solutions as “the” solution, we are concerned

that SE will soon be expected to provide answers to our most pressing social ills. In this paper

we call into question the ability of SE, by itself, to provide solutions on a scope necessary to

address large-scale social issues. SE cannot reasonably be expected to solve social problems on

a large scale for a variety of reasons. The first we label the organizational legitimacy argument.

This argument leads to our second argument, the isomorphism argument. We also advance three

other claims, the moral, political, and structural arguments. After making our arguments, we

explore ways in which SE, in concert with other social institutions, can effectively address social

ills. We also present two examples of successful ventures in which SEs partnered with

governments and other institutions.

4

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: THE ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS

“We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we

used when we created them.” (attributed to Albert Einstein)

There is no question that the world today faces numerous and severe problems. One need

not expend much time or effort to encounter them in the popular press—global warming,

poverty, increasing economic inequality, famine, potential pandemics, ethnic cleansing,

terrorism, etc. In addition to the specific problems we face, the virtual collapse of communism

and the effects of unbridled capitalism have exacerbated social injustices (Wolman and

Colamosca, 1997). Finding and implementing solutions to these problems is becoming critical to

our continued survival as a species (Carson, 1962; Gore, 2006).

Business, particularly a relatively small segment known as social entrepreneurship (SE),

is increasingly acknowledged as an effective source of solutions for a variety of social problems

(Mair, Robinson, and Hockerts, 2006; Nicholls, 2006). Because society tends to view “new”

solutions as “the” solution, we are concerned that SE will soon be expected to provide

comprehensive answers to our most pressing social ills. In this paper we call into question the

ability of SE, by itself, to provide solutions on a scope necessary to address large-scale social

issues. Certainly, there is anecdotal evidence that social entrepreneurs have addressed and

helped resolve many social problems (e.g., Bornstein, 2004; Leadbeater, 1997; Nicholls, 2004;

Nicholls, 2006; Nicholls and Cho, 2006). They have done so by being innovative, market-

oriented, and socially focused (Nicholls and Cho, 2006). But, to date, these successes have been

achieved locally and on a relatively small scale.

5

We will argue that as attempts are being made to scale up the field, SE by itself, is

inadequate to address the extent and complexity of the social problems we currently face; nor

should it be expected to do so. We do not make these arguments because we do not believe that

SE should address social issues. We are certainly not Friedman disciples, of the mind that the

sole social responsibility of business is to increase its profits (Friedman, 1970)—with one

exception, as we will explain later.

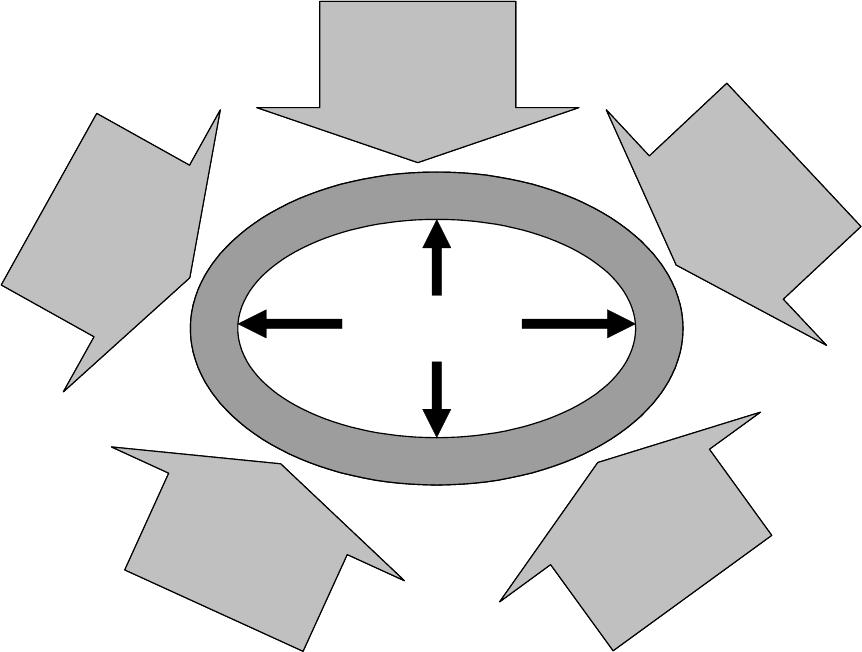

WHY SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP IS NOT ENOUGH

SE cannot reasonably be expected to solve social problems on a large scale for a variety

of reasons. The first we will label the organizational legitimacy argument. This argument is

closely related to, but separate from, (and, in many ways, a basis for) our second argument, the

isomorphism argument. We will also advance three other claims, the moral, political, and

structural arguments. These are depicted in the following model as forces restraining the

effectiveness of social entrepreneurship to solve wide-scale social problems.

---------------------

insert model here

---------------------

Our legitimacy argument is based on the fact that the very existence of certain types of

organizations depends upon the consent of the society in which they are embedded. This

acquiescence is based on the perception that a type of organization serves some sort of useful

purpose. For example, for-profit corporations are embraced by American society today, but were

highly discouraged and limited during the founding of the United States (Kelly, 2003; Nace,

2003; Grossman and Adams, 1993). Christian churches were all but obliterated in the USSR,

6

while they thrive in the United States. Private colleges are common in the United States, but

virtually non-existent in western European countries.

Organizational legitimacy, in the context of this argument, is a generalized perception or

assumption that the actions of an entity are socially desirable, proper or appropriate within some

socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions (Suchman, 1995). From an

institutional perspective, legitimacy is the means by which organizations obtain and maintain

resources (Oliver, 1991).

Social enterprises are the most recent organizational form, and as such, are still seeking

the legitimacy already accorded their predecessors. Historically, markets (i.e., private, for-profit

enterprise) have sometimes failed to provide certain goods or service. In contexts where

governments have not stepped in to resolve or ameliorate such failures, non-profits have

functioned as a vehicle to make these services available to citizens, thus gaining legitimacy for

the non-profit sector. It is important to be aware that the non-profit sector, by definition, has not

been driven by monetary profit and is solely concerned with filling the fissures that neither for-

profits nor governments have satisfied.

Social enterprises, which represent a fundamental innovation in the non-profit sector,

differ from non-profit organizations in terms of their strategies , structures, norms, and values

(Dart, 2004) and are considered a rational and functional alternative to public sector funding and

philanthropic resource constraints (Dees, Emerson & Economy, 2001). Just as non-profits

originated to address market and government failures, social enterprises are now being formed to

address the issues that for-profits, government, and non-profits miss. Scholars have viewed

social enterprises and social entrepreneurship as an “encompassing set of strategic responses to

7

many of the varieties of environmental turbulence and situational challenges that non profit

organizations face” (Dart, 2004).

Early definitions of the field suggest that social entrepreneurs play the role of change

agents in the social sector by adopting a mission to create and sustain social value, not just

private value (Dees, 1998). Although definitions in this emerging field remain fuzzy (Boschee,

1995; Dees, 1998), more recently there has been a broad acceptance of social entrepreneurship as

being an innovative use of resources to explore and exploit opportunities that meet a social need

in a sustainable manner. These classifications are closely related to widely accepted definitions

of entrepreneurship as the pursuit of opportunities without regard to resources under control

(Stevenson, 1985) and the scholarly examination of how, by whom and with what effect

opportunities to create goods and services are discovered, evaluated, and exploited

(Venkataraman, 1997).

The authors of this paper suggest that the similarities in the accepted definitions of these

fields are, in themselves, an indication that social enterprises are closer ideologically to for-profit

enterprises than to non-profits. The early emphasis of social entrepreneurs seems to have been

targeted towards innovation and using opportunities to create a social impact. However, as the

field has gained increasing recognition (i.e., legitimacy), and social entrepreneurs attempt to

scale their efforts, the lack of adequate resources increasingly will be felt. The ability to attract

and maintain resources is a key element in the search for legitimacy.

The evolving definitions of social entrepreneurship indirectly acknowledge this by

emphasizing the sustainability of their efforts. Traditionally non-profits have been funded by a

mixture of member fees, government funds, grants and user fees (DiMaggio & Anheir, 1990).

Social enterprises, on the other hand, are attempting to broaden this funding model by making

8

“strategic moves into new markets to subsidize their social activities either by exploiting

profitable opportunities in the core activities of their for profit subsidiaries or via for profit

subsidiary ventures and cross-sector partnerships with commercial corporations” (Nicholls,

2004). The number of stakeholders that social enterprises engage with is hence likely to be larger

than those for non-profits. The diverse expectation of these multiple stakeholders and the desire

to be self-sustaining is likely to further complicate these relationships. Significantly,

philanthropy is becoming more strategic in its largess, with donors calling for objective

performance metrics and financial transparency.

The preceding paragraphs describe a typical process—as social enterprises seek to scale

their efforts to address social problems, they need to acquire legitimacy as a class of

organization. However, in their efforts to bridge the traditional field of for-profit operations and

fill in the gaps left by governments and markets (the non-profit sector’s accustomed role),

financial results tend to subsume the social mission, if not in the social entrepreneur’s mind,

certainly in the reporting requirements for investors and donors (Bruck, 2006).

An early exemplar of this transition can be observed in the microfinance field. With the

arrival of private investment into the sector there have been calls to broaden its scope and

multiply its impact. Simultaneously, attempts are being made to reduce its dependence on

donors and government funding.

Citigroup, the world’s biggest bank, started a microfinance division in 2005. The

division’s global director commented, “[T]wo and a half billion people ha[ve] never used a bank.

Forty percent of the world is beyond the world we know” (Bruck, 2006: 68). As a financial bank,

the focus is likely to be on “financial inclusion” [gaining new customers for the bank’s services]

rather than reducing poverty. Mouhammed Yunus the founder of Grameen Bank and recent

9

Nobel Peace Prize winner, observed that the traditional goal of business—maximizing profit—is

inappropriate when dealing with the poor. In discussions with Pierre Omidyar of Ebay, who has

supported microfinance but called for a self-sustaining profitable model, Yunus said, “[W]hy do

you want to make money off the poor people? When they have enough flesh and blood in their

bodies, go and suck them, no problem. But, until then, don’t do that. Whatever money you are

taking away, keep it with them instead, so that they can come out more quickly from poverty”

(Bruck, 2006: 3).

We are concerned that the desire to gain legitimacy and avoid dependency on donors may

result in unintended consequences in a field still in its infancy. As a hybrid model emerges, we

see a blurring of the factors that have traditionally distinguished non-profits from for-profits,

such as goals, values, motivators, clientele, and types of clientele focus (Van Til, 1988;

DiMaggio and Anheir, 1990). Such a hybrid model may have the drawbacks of both

organizational forms with none of their individual advantages. This lateral movement from a

pro-social mission to a double (or triple) bottom line, accompanied by a desire to gain legitimacy

by emphasizing economic outcomes, may ultimately lead to the premature discrediting of a

promising field. Hence, we suggest that the role of institutions becomes critical to ensure that, as

the field expands, the desirable outcomes of SE are met, without compromising the essential

building blocks on which it has been founded and achieved early success.

Our second assertion is the isomorphism argument. Institutional isomorphism, as

originally defined, is “…a constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble

other units that face the same set of environmental conditions” in which “[o]rganizations

compete not just for resources and customers, but for political power and institutional legitimacy,

for social as well as economic fitness” (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983: 149-150). In other words,

10

organizations in similar fields tend to become more homogeneous over time. Note that the

isomorphism argument goes beyond that of the legitimacy argument—not only do organizations

need society’s approval to exist, but once they obtain that approbation, they are subject to

pressures to conform to existing modes of structure and operations.

DiMaggio and Powell (1983) go on to identify three mechanisms through which

institutional isomorphism operates: 1) coercive isomorphism—political or social pressures, 2)

mimetic isomorphism—responses to uncertainty, one of which is imitation of best practices, and

3) normative isomorphism—processes of rationalization through professional structures. These

mechanisms may result from either formal efforts or unofficial, even casual expectations.

We see clear evidence of all three of these mechanisms operating in SE. The rapid

proliferation of the field in academia and the emergence of numerous citizen organizations all

over the globe will gradually lead to social and political imperatives for conformity. This

process will be further accelerated, especially in the context of larger organizations, in their

desire for legitimacy and funding to promote their objectives. This point is an integral

component of both the legitimacy and isomorphism arguments.

Ashoka, a nonprofit entity organized in 1980, is dedicated to helping social entrepreneurs

build networks that will allow dissemination of approaches to resolving social problems.

Between 1990 and 2004 its operations spread from eight to forty-six countries, while increasing

the number of “Ashoka Fellows” from 200 to 1,400 (Bornstein, 2004). This is a clear example

of a formal effort to promote mimetic isomorphism within the SE field. This desire is prompted

by the reality that the field is in an initial phase of existence, with few successful models to

follow, and a plethora of problems to solve. Finally, normative pressures are now beginning to

exert themselves through professional structures within the SE field. Ironically, this pressure is

11

emanating primarily from large corporations, which, as they dedicate themselves to the field of

SE, are demanding greater accountability in their stated desire to achieve a higher impact (the

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is probably the best known example). Financial markets are

also beginning to play a part in forcing conformity within the SE field, as efforts to establish

structured investment exchanges are being developed (Bruck, 2006; Marketplace, 2007). Thus,

the theory of institutional isomorphism anticipates that social entrepreneurship initiatives will,

over time, increasingly resemble each other.

Nicholls and Cho, however, express concern that isomorphic pressures, inevitable in the

scaling process, may hinder the work of SE.

…[C]an social entrepreneurs adopt modes of rationalization and professionalization consistent

with the need to escape these [the tendency toward institutional isomorphism] pressures?

…[T]here is an ongoing process of antithesis that is a function of how social entrepreneurs

challenge existing, dysfunctional, social welfare delivery structures. Indeed, contra Marx and

Hegel, there seems to be no evidence that the move to a final synthesis is either desirable or likely.

The more social entrepreneurs continue to avoid institutional isomorphism and sectoral

assimilation by defying the logic of Hegelian-Marxian synthesis,…and the more systemic and

sustainable social impact they are likely to achieve (Nicholls and Cho, 2006: 116-117).

Although we anticipate that isomorphic forces will, as Nicholls and Cho (2006) predict,

inhibit the effectiveness of SE, we also recognize that certain factors will mitigate those forces.

These mitigating factors will help SE maintain effectiveness, but they will also limit the scale

upon which SE will operate. One such factor mitigating the general operation of institutional

isomorphism in the SE field is the very nature of what social entrepreneurs do. SE has been

characterized as a form of Schumpeterian entrepreneurship, a disruptive force that acts as

“…change agents for society, seizing opportunities others miss and improving systems,

inventing new approaches and creating sustainable solutions to change society for the better”

(Skoll Foundation, 2005). Certainly, Schumpeterian entrepreneurs are not inherently immune to

the forces of institutional isomorphism (e.g., witness the railroad, pharmaceutical, and computer

industries; or the multinational firm). All were disruptive agents of “creative destruction”

12

(Schumpeter, 1942), but are now relatively homogeneous factors in the economy. However, SE

operates in a wide variety of cultures, geographic locales, and social problems, implying that it

may not be as susceptible to the forces of institutional isomorphism as are many other industries

and organizational forms. “As a consequence, social entrepreneurs can avoid many of the

coercive isomorphic pressures typically experienced by other organizations from outside

forces.…[T]he bespoke diversity of much successful social action plays against mimetic forces

and embodies a focus on social objectives rather than organizational form….Using a legitimacy

framework to explore the dynamic effectiveness of social entrepreneurship reveals not only their

[sic] resistance to institutional isomorphic pressures…” (Nicholls and Cho, 2006: 114-115).

Social entrepreneurs, virtually by definition, are attacking social problems caused by

shortcomings in existing markets and social welfare systems (Mair, Robinson, and Hockerts,

2006; Nicholls, 2006). The institutions that comprise these markets and social welfare systems

are part of the structure that created those very social problems (refer back to Einstein’s quote at

the beginning of this paper). Those market and welfare institutions are also clearly much further

along in the process of institutional isomorphism than are social entrepreneurs. Their existing

power and legitimacy will tend to resist the widespread isomorphism of SE, if for no other

reason than to protect their own status.

Although social entrepreneurs may be able to address specific social problems more

effectively if they resist the forces of institutional isomorphism, they will also be less likely to

bring about the broad and comprehensive reforms needed to bring about widespread solutions to

those problems. “They [social entrepreneurs] defy the traditional isomorphic forces that often

constrain and categorize organizational innovation…preferring instead constantly to challenge

13

the status quo by reconfiguring accepted value creation boundaries (public/private, for-profit/not-

for-profit, and economic/social)” (Nicholls, 2006: 11).

Our third argument why SE will be unable to resolve social problems is the moral

argument. To fully understand this argument, it is necessary to trace some facets of Western

history. The amoral theory of business (Shepard et. al., 1995) is currently the dominant

paradigm in our society, one in which the economic institution is viewed as somewhat separate

from the other institutions and immune to some moral regulations. This paradigm is the result of

the shift, beginning in the seventeenth century, from the “moral-unity” theory of business to the

“amoral theory of business” (Shepard et. al., 1995). The moral-unity theory of business

postulates that the economic institution is viewed as an integral part of the overall society, and

that it is subject to all of the same norms and moral regulations as all of the other social

institutions. In contrast, the amoral theory of business sees the economic institution as separate

from other social institutions, largely insulated from all of the moral norms followed in the rest

of society. It is imperative to note that the moral-unity theory of business, as well as the amoral

theory of business, pertain to how people view the economic institution and how they behave—

not whether the economic institution is, in fact, normative or amoral.

In this shift, the economic institution has been separated morally in certain significant

ways from other social institutions such as the church, the state, the community, and the family.

As a result, the economic institution has come to be exempt from some generally accepted

norms. Or, as some have stated, the economic norms have become the only ones that matter.

You may prefer to think it’s just a leftist structural theory that labor and export market stability are

often the underlying reasons for various U. S. sanctions, military actions, and other foreign

policies. Or you can just read Investor’s Daily Business and the like, when such things are often

spelled out explicitly by the players themselves, with remarkably little concept that any other

paradigm for human behavior might exist (Harris, 1999: 122-123).

14

Shepard et. al. (1995) point to several factors in this shift from the moral-unity to the

amoral theory of business. From the earliest Western civilizations, the dominant ideology was

uniformly communitarian. In ancient Greece, the prevailing view was that individuals existed

only within the context of the overall society and that economic activity was a necessary evil,

useful only to provide the necessities of life. Early Christians held views similar to the Greeks

on the relation between the individual and economic activities. With the birth of Jesus and the

establishment of the Christian church (then the Catholic Church), most Western societies were

unified under the domination of the church, clearly representing the moral-unity theory. A

significant turning point came with the Protestant Reformation, and its notion that individuals

could have a direct relation with their God, without the intervention of the church. This novel

idea laid the groundwork for the first true recognition of the individual as an entity separate and

apart from society. Calvinism and its revolutionary idea of predestination inadvertently provided

further impetus for the acceptance of economic activity, and for the first time, approved the

accumulation of individual wealth—albeit towards the end of communitarian purposes.

Although neither Luther nor Calvin intended to do so, both of their doctrines promoted

the acceptability of a more individualistic ideology. This in turn provided fertile ground in

which the spirit of capitalism could grow, as documented by Weber (1904-05/1958). Weber

viewed the development of rationalism as an integral component of the development of the spirit

of capitalism. Along with the Enlightenment’s conviction that humans could, through reason

alone, solve the puzzles of the universe, it was a short road to the belief that man was his own

master (a notion completely foreign to Luther and Calvin). This notion reduced the influence of

the church, and gradually, economic activity was placed in a special domain somewhat removed

15

from moral rules associated with other social institutions; this separation constitutes the amoral

theory of business.

Two major themes arise from this intellectual history. The first is the rise of the

individual as an entity separate from the society in which she is situated. Nisbet (1993) refers to

this as the process of individualization, or the separation of individuals from communal social

structures. The new societies heralded the rise of moral egoism and social atomization. The

second theme is the separation of the economy from other social institutions. Beginning with the

ancient Greeks, Western civilization had viewed society as composed of unified institutions,

including the family, the state, the church, and the economy. However, because of the forces just

outlined, people came to see the economy as separate in some ways from other institutions. Both

of the processes described by these themes have been instrumental in the rise of the amoral

theory of business. In turn, this paradigm is quite possibly a major contributor to the expectation

that SE can, by itself, solve many of our current social problems.

Emile Durkheim, like other early sociologists, had seen the effects of the profound

disruption of society engendered by the shift just outlined, including the growing separation of

the economy from the rest of society: “For two centuries economic life has taken on an

expansion it never knew before. From being a secondary function, despised and left to inferior

classes, it passed on to one of first rank” (Durkheim, 1937/1996: 11). In Professional Ethics and

Civic Morals, Durkheim explored the problems of an advanced, complex society in which the

economy had become so detached from other social institutions that it became an end in itself.

He wrote that in Western societies neither government nor society held moral sway over the

economic institution; a state of anarchy within the economic sphere was therefore inevitable. He

made several references to “the anarchy of the economy” in this work (a concept virtually

16

identical to the amoral theory of business.) According to Durkheim, “We can give some idea of

the present situation by saying that the greater part of the social functions (and this greater part

means to-day the economic—so wide is their range) are almost devoid of any moral influence…”

(Durkheim, 1937/1996: 29). Durkheim would argue that social institutions external to business

must provide effective moral guideposts for SE.

As Victor and Stephens (1994) note, for all intents and purposes, everything and nothing

has changed since Durkheim, over one hundred years ago, gave the lectures that now comprise

Professional Ethics and Civic Morals. In some ways the milieux are eerily similar. Instead of

the Industrial Revolution, we are now undergoing the Information Revolution, and instead of

shifting from an agrarian society to an industrial one, we are in the midst of the transition from

industrial society to a post-industrial society. Durkheim saw the effects of the transition from an

agriculturally based economy to an industrial one, and we are seeing the shift to a service and

information-based economy. Finally, we, like Durkheim, are still looking for an institution that

can instill morals into the economic institutions; Durkheim was correct when he observed that

the market in a capitalistic economy has difficulty imposing a set of moral rules on the

participants in that market. As Turner notes, “The problem facing modern Europe [and the

United States] is the separation of the economy from society and the absence of any effective

regulation of the market place” (Turner, 1996: xxxi). Society today is undergoing many of the

same types of social upheavals, with the same types of effects that Durkheim witnessed a century

ago. Francis Fukuyama has termed this the “Great Disruption” in the social values that had

prevailed in the industrial-age society of the mid-twentieth century.

This period, roughly the mid-1960s to the early 1990s, was also marked by seriously deteriorating

social conditions in most of the industrialized world. Crime and social disorder began to rise,

making inner-city areas of the wealthiest societies on earth almost uninhabitable. The decline of

kinship as a social institution, which has been going on for more than 200 years, accelerated

sharply in the second half of the twentieth century. Marriages and births declined and divorce

17

soared; and one out of every three children in the United States and more than half of all children

in Scandinavia were born out of wedlock. Finally, trust and confidence in institutions went into a

forty-year decline (Fukuyama, 1999:55-56).

Durkheim’s concern over the social chaos in his time is clearly still relevant today.

Within the economic sphere, one of the common indicators of this condition is the continued

prevalence of unethical business practices. To expect that any business institution, even SE, can

provide the moral leadership needed to resolve multiple, large, complex social problems is

simply unreasonable.

In essence, Durkheim anticipated our argument over one hundred years ago. His concern

about the effects of the removal of moral constraints on economic behavior mirrors ours. To the

extent that the good of all parties is not considered pertinent to economic activities (as is the case

under the amoral theory of business), the growth of SE will be retarded.

The fourth reason that SE, as it scales up, is not likely to be an effective solo agent to

resolve social problems we refer to as the political argument. Albert Cho (2006) makes the

highly relevant point that the “social” in SE is vacuous unless and until it is defined—and the

process of definition is, itself, fraught with tensions. Existing definitions of SE are clearly

approbative—but they fail to delineate what social ends are being pursued. Until the social end

is specified, Cho maintains that it is impossible to make value judgments about the benefits of

SE. For example, consider the social end of providing access to abortion procedures. If one

happens to be “pro-choice,” the existence of a social venture to ensure access to abortion

procedures is probably a good thing; but if one is “pro-life,” it is anathema.

He also points out that the process of establishing social ends is political, and that the

political process is entangled in values; and those values may be different depending on whether

they are conceived of in the private or public sphere. Thus, unless the social end pursued by a

18

social entrepreneur has been determined through a public political process, that end is simply one

person’s conception of “the good” (Cho, 2006).

The relevance of Cho’s concerns in the current context is that, absent some method of

reaching agreement about the desirability of particular social ends, SE is subject to varied

degrees of approval and support from entities external to the social entrepreneur. If general

support from external bodies is limited (due to disagreement with the social end or alienation

from the process of determining the end), SE will not be as effective as it otherwise could be.

Thus, at the very least, social entrepreneurs are dependent on processes external to them to set

generally approved social goals. “Yet the act of defining the domain of the social inevitably

requires exclusionary and ultimately political choices about which concerns can claim to be in

society’s ‘true’ interest. These choices reveal that, despite its protestations to the contrary, SE by

its very nature is always already a political phenomenon” (Cho, 2006: 36, author’s emphasis)

The final argument we advance here is the structural argument. Simply put, this argument

states that the very structure of a capitalistic economy works against the idea of SE. The crux of

this argument is contained in the inherent tension that all business enterprises face: competitive

advantage (i.e., self interest) versus corporate social responsibility (i.e., interest in others’

welfare). In more detail, this argument is that the current way we view competition in the

marketplace makes it unlikely that business people, even social entrepreneurs, will pursue

socially beneficial ends.

The premises and conclusion of the argument are:

• The structure of the American economy has evolved into a bifurcated system of

large, powerful companies and relatively small, powerless organizations

(Galbraith, 1967).

19

• Because of this division in the economic system, the original meaning of

competition, as envisioned by Adam Smith (1776/1986), has been bastardized

into “winning” or “maximizing profits.”

• The emphasis on winning causes self-interested behavior—adherence to ethical

egoism.

• Acting in an exclusively self-interested manner (often referred to as ethical

egoism) renders integrity impossible (McFall, 1987).

• Therefore self-interested behaviors by business practitioners are more likely to

occur than are socially beneficial behaviors (VanSandt, 2002).

The emphasis on “winning” is a cultural phenomenon that is prevalent in the West,

especially in America. Alfie Kohn characterizes winning as “a capsule description of our entire

culture” (Kohn, 1992: 3). Winning and losing are the central components of structural

competition. “To say that an activity is structurally competitive is to say that it is characterized

by what I will call mutually exclusive goal attainment….This means, very simply, that my

success requires your failure” (Kohn, 1992: 4).

The nascent field of SE studies implicitly recognizes this propensity toward self interest

and winning, and the dichotomy between self interested behaviors and other-directed behaviors.

“[U]nlike business entrepreneurs who are motivated by profits, social entrepreneurs are

motivated to improve society” (Skoll Foundation, 2005). We must acknowledge at this point

that we realize that, in some ways, we are calling into question the most basic assumptions about

capitalism. Adam Smith is popularly thought to have argued in Wealth of Nations that self

interest is the basis upon which an economy creates wealth for all. “It is not from the

benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their

regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love,

and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages” (Smith, 1776/1986: 26-

27).

20

Smith’s supposed reliance on self interest to guide economic activity is understandable

when one focuses on personal gain; but the title of his book, Wealth of Nations, reveals his true

purpose. Smith hoped to show how an economy could be structured so that it benefited everyone

in the nation, not just a few lucky (or hard-working) individuals (Muller, 1993). Unfortunately,

he did not provide much in the way of an explanation about how that would work. Instead, he

relied on the now famous “invisible hand” explanation to show how self interest would work to

benefit all.

But the annual revenue of every society is always precisely equal to the exchangeable value of the

whole annual produce of its industry….As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he

can both the employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry

that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the

annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote

the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic

to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such

a manner as its produce my be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this,

as in many other cases led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his

intention….By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more

effectually than when he really intends to promote it (Smith, 1776: 265).

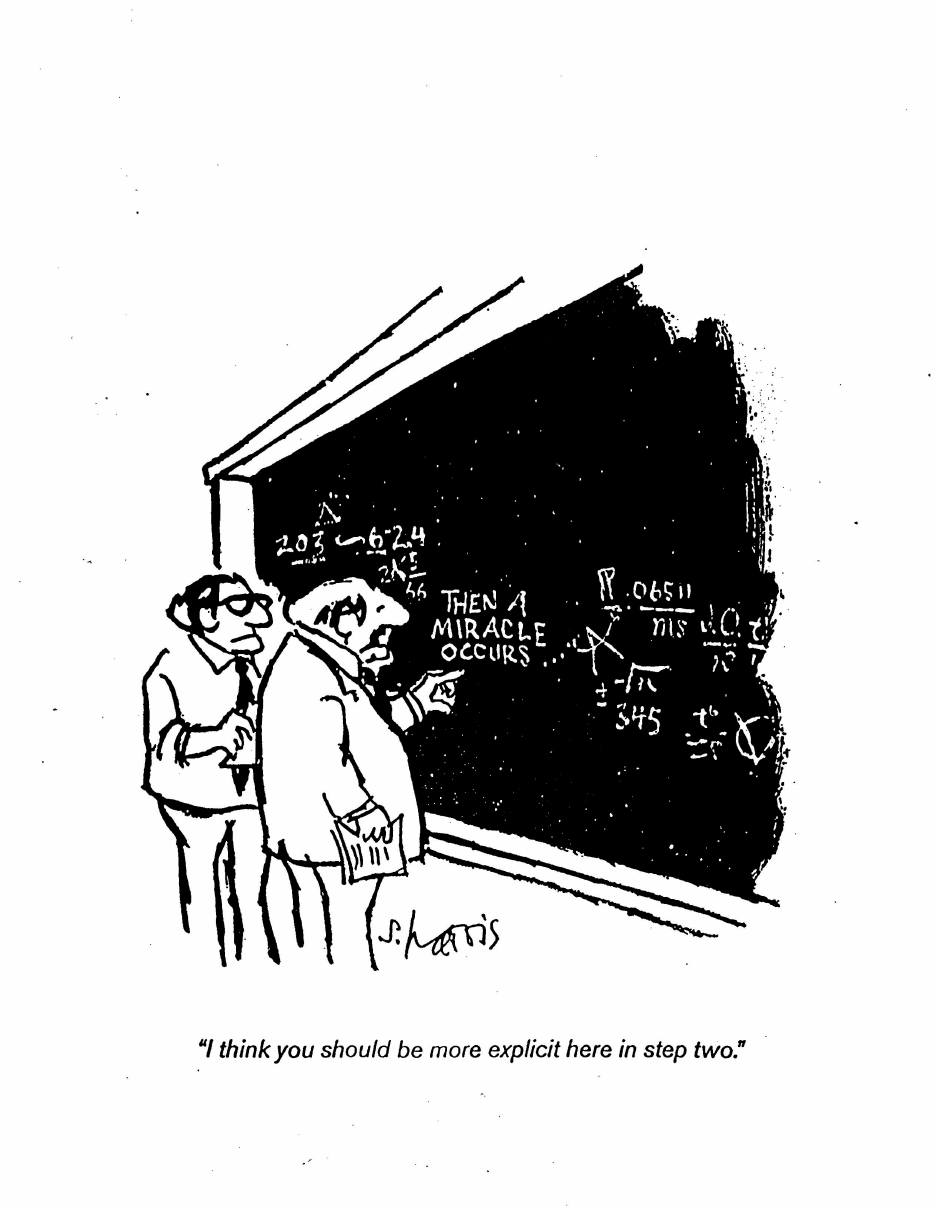

Smith’s assertion is akin to the cartoon in which one sophisticated mathematician is

presenting his proof, with an intermediate step of “…then a miracle occurs,” only to be critiqued

by another, who says, “I think you should be more explicit here in step two.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

insert cartoon about here

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Smith failed to provide any support for his contention, and was later contradicted by another

economist, who said, “Left to themselves, economic forces do not work out for the best except

perhaps for the powerful” (Galbraith, 1973: xiii).

Although there certainly are successful, selfless social entrepreneurs, they are a minute

minority of the population. Because these SEs so clearly stand out from the population of

21

business entrepreneurs, they are the exceptions that prove the rule inherent in the structural

argument—that individual economic gain is the primary motivation for business entrepreneurs.

Early research efforts in the field of SE implicitly recognize this by concentrating on: “profiles

of ‘hero’ social entrepreneurs” (Nicholls and Cho, 2006: 99), or by asking if they are “‘world-

historical individuals’, heroic men and women ‘with insight into what was needed and what was

timely’, whose ‘deeds and…words are the best of their time’?” (Nicholls and Cho, 2006: 106,

quoting Hegel, 1988: 32). Expecting that such a small percentage of the population, even if they

are truly heroic, can make a sizeable dent in the plethora of social problems is simply unrealistic.

It is equally unrealistic to expect, given the way markets operate, entrepreneurs to be

motivated solely to address socially beneficial issues. In one of the examples, which addresses a

pressing housing problem in Mumbai, India, an entrepreneur clearly states, “It makes a lot of

investment sense for us. We are not here just to serve a social cause” (Architecture for

Humanity, 2007). We must strike a note of caution here. Foundations like the Grameen bank

have demonstrated that providing financial services to rural communities and micro-

entrepreneurs can be achieved on a sustainable and scalable basis. This has resulted in

developments which cause us concern. As we described as part of the legitimacy argument,

existing financial institutions have begun to enter the microfinance field. We call into question

whether the traditional goal of profit maximization, that these for-profit organizations espouse, is

appropriate in dealing with the poor.

HOW THEN SHALL WE PROCEED?

If SE is not the answer to our social ills, then what is? Certainly not business in

general—many argue that it has contributed far more to social problems than it has to alleviating

them (Derber, 1998; Ehrenreich, 2001; Kelly, 2003; Korten, 1995; Nace, 2003; Shulman, 2003).

22

Governments, in all their various forms, seem almost entirely incapable of “fixing” the social

problems their citizens face. Religion appears to have virtually abdicated its influence in the

West, along with its emphasis on helping the disadvantaged. “However, the decline of organized

religion in some cultures has provided another set of social market failures” (Nicholls, 2006: 9).

It is our contention that no single social institution—an organizational system which

functions to satisfy basic social needs by providing an ordered framework linking the individual

to the larger culture (Shepard, 2005)—is capable of resolving the large-scale problems now

facing us, or those yet to come. It will take the collaborative efforts of many different sectors to

effectively address our complex social problems. As Albert Einstein is purported to have said,

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” If our social problems cut

across institutional boundaries (as they all do), Einstein would tell us that all of those institutions

must be involved in the solutions.

Although collaborative efforts among social institutions sounds good on paper, the

current imbalance of power may impede their ability to do so. Business, or the economy, is

clearly the dominant social institution in the West, and has been for more than two centuries

(Durkheim, 1937/1996: 11; Etzioni, 1991). This fact, by itself, is not necessarily indicative of

anything. However, problems arise when the “currency” of one social sphere gains influence in

another sphere (Walzer, 1983). As an example, consider the influence that money (the currency

of the economy) has gained in the political sphere (whose currency ideally includes ideas,

justice, and morality). Money’s influence in other spheres often manifests itself in the form of a

single criterion for decision-making—that of profit, or other form of monetary gain.

SE scholars are fond of talking about the “double” or even “triple” bottom line. We

agree with the desirability of such an approach. However, until we acknowledge that only one of

23

those lines—monetary profit—really matters to a large majority of decision makers, our calls for

more social justice will remain largely unanswered. Other social institutions, especially

government, religion, and education must be intimately involved in finding solutions to our

social problems. The current imbalance is built into our social structures, as one legal scholar

notes, “I realized that the many social ills created by corporations stem directly from corporate

law. It dawned on me that the law, in its current form, actually inhibits executives and

corporations from being socially responsible” (Hinkley, 2002: 4, author’s emphasis).

We mentioned previously that we are not Friedman disciples, except in one instance. His

philosophy of corporate social responsibility is summed up in his directive, “…there is one and

only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed

to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game…” (Friedman, 1962: 133).

Currently, for all practical purposes, business makes up its own rules of the game (Kelly, 2003;

Korten, 1995; Nace, 2003; Stone, 1975). Until other social institutions provide an effective

counterbalance to business’s influence, and help develop more just “rules,” the second and third

bottom lines will continue to be effectively ignored.

HOW CAN SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS WORK TOGETHER?

James Rest, building on the work of Lawrence Kohlberg and Jean Piaget, developed a

model of activities necessary for moral behavior to occur. His Four Component Model specifies

that a moral agent must: 1) become sensitive to, or aware of, the moral situation; 2) make moral

judgments about the situation; 3) be sufficiently motivated to act, and 4) have courage to follow

through with the action. Other than needing to become aware of a moral situation before any of

the other steps can occur, Rest is careful to say that his four components do not necessarily occur

in sequence, and they are likely to interact (Rest, 1994). This model is a useful tool for

24

analyzing the likelihood that moral behavior (in this particular instance, SE) will occur. If the

amoral theory of business is accurate, we would expect repeated failure in any and all of the four

steps. With business practitioners’ moral capabilities artificially truncated, it becomes clear that

other social institutions’ input is necessary. As one author notes, “Childline [an SE venture in

India] and the Grameen Bank could not have achieved national and global impact without the

financing and the legitimacy they received from governments” (Bornstein, 2004: 269). Below,

we postulate ways in which dissimilar social institutions might use Rest’s framework in order to

work together to solve social problems.

Awareness – The initial recognition that a social problem exists, and carries with it moral

implications, may arise from a plethora of sources. For example, a religious order might

recognize that a number of its parishioners need basic medical care. Lacking the ability to

provide those services by itself, it might enlist government agencies or SEs to address the

problem. Our moral argument clarifies the point that viewing business as an amoral enterprise

severely limits the operation of moral awareness. Seeing business as an undertaking with moral

implications is necessary for moral awareness to operate.

Judgment – Moral judgment is the topic about which philosophers have been debating for

more than two millennia. To assume that SEs, operating in a vacuum, would know the “right”

actions to take, gives them much more credit than they are due. As we point out in the political

argument, social ends may be highly contentious (take the pro-choice/right to life debate as one

example). The process for establishing social ends is necessarily political, and in many cases,

would include input from other social institutions, such as the family, religion, or education.

Motivation – As the Skoll Foundation points out on its website, SEs are motivated by

more than just the bottom line; they seek to improve society. However, we present the case in

25

the structural argument that we cannot rely solely on SEs beneficence. The profit motive is too

strong in our society to realistically believe that a subset of the economic institution will be able

to bring about widespread social improvements. Therefore, other social institutions like

governments, religious orders, and educational systems must become involved to either change

societal values or provide a system of rules that guide economic behavior toward more social

ends.

Courage – Rest points out, “A person may be morally sensitive, may make good moral

judgments, and may place high priority on moral values, but if the person wilts under pressure, is

easily distracted or discouraged, is a wimp and weak-willed, then moral failure occurs because of

deficiency in Component IV (weak character)” (Rest, 1994: 24) Some of the defining

characteristics of SEs are their extraordinary devotion to their causes and their persistence in the

face of often overwhelming obstacles (Bornstein, 2004; Nicholls, 2004, 2006). Although these

are obviously commendable qualities, they are not a sound basis upon which to build a system of

social justice. “We want [people] with moral courage. Yet we must strive to create

organizations where moral courage is not needed” (Kidder, 2005: 179). As we have discussed in

the isomorphism argument, SEs’ ultimate goal is to change the system itself, so that the obstacles

they (and more importantly, their clients) encounter cease to exist (Skoll Foundation, 2005;

Nicholls and Cho, 2006). Because these obstacles are the products of a wide range of social

institutions, all of those institutions must be involved in their destruction.

EXAMPLES

We have argued that as SE attempts to scale up, it will, by itself, be unable to solve the

social problems we currently face. For a variety of reasons, it will take a joint effort by several

social institutions to effectively address those issues. As we show in the following examples,

26

varied social institutions are working with SEs to address some of the most profound social

problems currently faced. These institutions include governments, education systems, and for-

profit businesses. These examples provide clear evidence that our arguments are sound, and that

such inter-institutional collaboration is a necessary element in addressing our most serious social

ills.

One Laptop Per Child

“This is not just a matter of giving a laptop to each child, as if bestowing

on them some magical charm. The magic lies within—within each child, within

each scientist—, scholar—, or just-plain-citizen-in-the-making. This initiative

is meant to bring it forth into the light of day.”

Kofi Annan

Founded in 2005, it has been only a few short years since Nicholas Negroponte presented

his vision for a global educational program to the World Economic Forum in Davros,

Switzerland. Joined by technological heavyweights, AMD, Google and News Corp, Negroponte

outlined his strategy for providing “…children around the world with new opportunities to

explore, experiment, and express themselves.” Negroponte’s organization, One Laptop Per

Child (OLPC), has chosen a bold and unique approach for achieving this goal.

The strategy undertaken to reach these ends involves the coordination of experts in

technological design and manufacturing, as well as educational research and international

relations (representing the social institutions of business, education, and government) to develop

a means by which children in underdeveloped nations and communities can enhance their own

learning process. Based on research by Seymour Papert, an MIT professor and renowned expert

on artificial intelligence and the use of technology in early education, and espoused by

Negroponte in his book Being Digital, the organization has developed a rugged, energy-efficient,

27

internet-capable laptop, called the XO, installed with software designed specifically to allow

children not only access to the world via the internet, but also the capability to manipulate and

experiment with programming in order to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Though the goals to which Negroponte and the One Laptop Per Child organization aspire

to have met with little criticism, it is the strategy executed that has instigated the most

controversy and evoked many pressures from outside constituencies that have attempted to

inhibit the growth and achievements of the OLPC organization. Negroponte’s organization has

met with resistance from certain factions within for-profit technology organizations, educational

research, and governments of those countries targeted for distribution of OLPC’s machines.

Particular resistance stemmed from one of the key goals set forth by the OLPC, to build a

computer for less than $100. This price point, though recently deemed unachievable, was set in

the hopes that such a relatively low price for a fully functioning laptop would allow countries to

buy larger quantities of laptops for their own educational systems. However, at the same time,

the market has been pressuring laptop manufacturers to lower prices. The existence of a $100

laptop concerned many manufacturers who were actively working to lower the price of laptops

over a longer term. Moreover, many computer manufacturers were already planning and/or

producing laptops designed for children (e.g., Intel and Asus) and had begun attempting to

garner market share in developing countries for their own products. The development of the

OLPC’s XO represents not only a potentially acute downward force on current laptop prices, but

also represented direct and vital competition for what has been estimated to be billions of

potential customers.

Additionally, the success of the OLPC initiative hinges on the buy-in by the leaders of

developing countries. While countries such as Brazil, Urugay, Libya, Rwanda, and others have

28

ceremoniously committed to the OLPC cause, follow-through with orders on the magnitude

expected by OLPC has fallen short. Moreover, countries aggressively sought out by the OLPC,

including India and China have shown wavering interest in the program. In both cases,

politically oriented concerns have been raised as to whether or not these countries could use their

own advanced technological know-how to create machines within their own countries. To

partially counter these obstacles, the OLPC plans to sell XO machines for $400 in a “give 1, get

1” campaign within the United States, a marked change in strategy, for a two week period in

November of 2007 in order to generate interest and funding to jumpstart the dissemination of the

machines in target countries.

Though these are just two of the influential challenges for the OLPC organization, they

represent well the conflict experienced by social entrepreneurs as their organizations begin to

gain momentum. The more support the OLPC gains in terms of its mission, the more pressure

the organization faces to conform to the expectations of powerful, yet unintentional,

constituencies. For example, as OLPC began to make progress toward the design and production

of a much more durable, efficient, and economical computing machine isomorphic pressure was

applied by both the technological and educational industries to mold OLPC’s approach into an

approach more traditional, and thereby less threatening, model. Moreover, though the leadership

of many countries agree, in principle, with the goals of the OLPC organization and realize the

potential for significant long-term benefits, they seem to resist the achievement of those goals in

ways that do not directly, and in the short-term, benefit those nations. These structural and

political pressures created clear and challenging obstacles to the OLPC programs progress.

Recent events have indicated that the OLPC organization is taking action to address these

isomorphic, political, and structural pressures. For example, in 2007 the OLPC created a

29

position on their Board for a representative from Intel, historically their most staunch and bitter

competition. This unlikely collaboration between not-for-profit and for-profit organizations,

while surprising many observers, was explained by Negroponte as a way for the OLPC

organization to maximize the number of laptops distributed to children around the world.

Additionally, the OLPC organization has responded to political and structural pressures

by shifting their marketing strategy from a primary emphasis on persuading national educational

and political leaders of target countries to working directly with local and regional leadership of

target nations in order to build demand from within. While the outcome of this new strategic

approach remains to be seen, early evidence indicates that the OLPC organization may make

stronger headway toward achieving its mission. In fact, in October of 2007, after an initial

rejection by the Indian government in order to evaluate India’s ability to build its own program

from within, a pilot program was begun at Khairat School in Khairat-Dhangarwada, a small

village in Maharashtra State, India.

Dharavi-The make over of the largest slum in Asia

The root cause of urban slumming seems to

lie not in urban poverty but in urban wealth.

Gita Verma

The operational definition of a slum is poor or informal housing which is characterized

by overcrowding, inadequate access to safe water and sanitation, and has insecurity of tenure.

The United Nations has estimated that more than a billion people—a third of the urban

population—live in slums and that these numbers are expected to swell as the rural exodus

continues.

30

Dharavi houses close to a million people squeezed into 550 acres of swampy landfill in

the center of India’s financial capital, Mumbai. Sewage filled gutters (there is a toilet for every

1,440 residents), rickety ramshackle homes, labyrinthine lanes so crowded with shanties that

little sunlight penetrates and garbage piles everywhere are a common sight in what is probably

Asia’s largest slum. This place is booming, however, with sometimes highly polluting industrial

activity. A thriving pottery business exists where potters have passed on their craft through

generations. Other industries include soap making, chemical manufacturing, and recycling, all of

which have existed side by side with sweat shops, in which workers on sewing machines toil for

long hours in tiny rooms. It has been estimated that the annual gross revenues of business

emanating from Dharavi is approximately $650 million.

The residents are also a source of cheap, skilled and unskilled labor that is desperately

required to help keep the wheels of India’s financial capital moving. However, successive

governments’ apathy toward their citizens’ well-being, the prohibitive cost of housing in the city,

and the regular influx of people has further aggravated a serious housing problem. Despite a

number of attempts over the past few decades to address this issue and get the squatters evicted

from what is now valuable government land, it has remained an intractable problem. This is due

in no small measure to the so-called “vote bank politics” prevalent here. Local democratically

elected governments have turned a blind eye simply because the densely populated areas serve as

a source of votes during elections. A number of attempts, over the years, by the city’s slum

clearance board have also been unsuccessful.

Historically, slum rehabilitation has been addressed on a piecemeal basis, more often

being tackled as a housing, rather than a socio-economic problem. This has resulted in the lack

of any sustainable model of rehabilitation. The Dharavi Redeployment Project (DRP), a public/

31

private partnership has adopted a significantly different approach on three fronts. If successful,

this model could be a blueprint for slum rehabilitation all over the world.

First, it attempts to treat slum dwellers as a valuable human resource that can act as a

cornerstone of a vibrant and robust economy. Unlike previous urban planning initiatives, DRP

seeks to integrate slum areas with the rest of the city in order to provide sustainable

development. The project recognizes both the need of the slum dwellers to continue their

livelihood, as well as the necessity of providing them infrastructure for HIKES (Heath, Income,

Knowledge, Environment and Socio-cultural development). Significantly, the plan envisages

full deployment of slum dwellers and transit accommodation until the project is completed,

within the same areas where they now reside. Attempts are being made to upgrade their skills

while maintaining their vocation (e.g., people who for many generations have been engaged in

pottery will be provided training to improve their skill sets using other mediums, such as

ceramics, while opportunities will be provided to them to market their crafts locally as well as a

potential export market).

Secondly, in anticipation of likely moral and structural pressures that might arise, the

plan has involved the private sector. International developers have been invited to transform

Dharavi into an integrated township with all modern civic amenities and complete infrastructure,

including entrepreneurial zones where small businesses could be run. Under the proposal each

family would be entitled to a 225 square foot dwelling unit equipped with proper sanitation in

mid- and high-rise buildings. Approximately 36.6 million square feet of liveable space will be

constructed by the top five bidders, each of whom would be allotted a 107 acre zone. In

exchange for providing local inhabitants with free homes and licensed industrial space, the

successful builders will have the right to develop an additional 43.5 million square feet in the

32

open spaces freed up by relocating the slum dwellers, which they would be allowed to sell or

lease commercially.

Finally, the government is confining its role to that of a facilitator. The original idea was

conceived by an architect who has since been invited to join the DRP and has been made the

project management consultant. To preempt likely political pressures that this model might face

NGO’s have been entrusted with spreading awareness of the benefits of the scheme and

legislation introduced that the slum resettlement proceeds after seventy percent of households

sign up for it. The Free Space Index (FSI) also know as FAR, (the square footage of area a

builder is typically allowed to construct) has been increased to ensure viability of the project.

The government is thus clearly luring private builders both with the promise of huge returns on

their investments and the ability to participate in a noble cause.

Traditionally, the common approach for slum development has been for the government

to sanction slum clearance and then build low cost housing with public funds. Toshi Noda, Asia

Director of the United Nations Human Settlement Program (UN-Habitat) said, “Free apartments

is not common. It is a new scheme. I think it will work because the private sector can get their

profit by developing the other half of the real estate” (Giridharadas, 2006).

Besides heralding it as a financial “opportunity of a life time” for prospective builders,

the Global Expression of Interest highlighted the opportunity to participate in a noble cause with

huge social benefits. A director of a New York investment fund was recently quoted in the local

media as saying, “It makes a lot of investment sense for us. We’re not here just to serve a social

cause” (Architecture for Humanity, 2007).

The project, which is now at the bidding phase, is likely to take six to seven years to

complete. The Global Expression of Interest advertisement, inviting prospective bidders, was

33

published in May 2007. Short listing of bidders is in progress. Simultaneously, an

environmental impact assessment in each of the five sectors of the redevelopment is in progress.

The initial response from the international community has been overwhelmingly positive with

top-flight builders submitting offers, which are in the process of being evaluated. Mumbai’s

Dharvai makeover is an exemplar of how social entrepreneurship can succeed by engaging other

institutions.

34

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Architecture for Humanity, 2007. “Dharavi.”

http://www.architectureforhumanity.org/programs/Settlements/dharavi.html.

Bornstein, D. 2004. How to Change the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Boschee, J. 1995. “Social Entrepreneurship.” Across the Board 32(3): 20-5.

Bruck, C. 2006. “Millions for Millions.” New Yorker. October 30.

Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cho, A. 2006. “Politics, Values and Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Appraisal.” In J. Mair, J.

Robinson and K. Hockerts (Eds.), Social Entrepreneurship. Houndmills, Basingstoke,

Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dart, R. 2004. “The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership,

14(4) : 411-424.

Dees, J. 1998. “Enterprising Nonprofits.” Harvard Business Review Jan-Feb 55-67.

Dees, J., J. Emerson, and P. Economy. 2001. Enterprising Nonprofits: A Toolkit for Social

Entrepreneurs. New York: Wiley.

Derber, C. 1998. Corporation Nation: How Corporations are Taking Over Our Lives and What

We can do about it. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Di Maggio, P. and H. Anheier. 1990. “The Sociology of Nonprofit Organizations and Sectors.”

Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 137-159.

DiMaggio, P., and W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and

Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review (48).

147-160.

Durkheim, E. 1937/1996. Professional Ethics and Civic Morals. London: Routledge.

Ehrenreich, B. 2001. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. New York:

Metropolitan Books.

Etzioni, A. 1991. “Reflections on the Teaching of Business Ethics.” Business Ethics Quarterly 1

(4). 355-365.

Friedman, M. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. 1970. “Social Responsibility of Business.” The New York Times Magazine Section.

September 13.

Fukuyama, F. 1999. “The Great Disruption.” The Atlantic Monthly (283). 55-80.

Galbraith, J. 1967. The New Industrial State. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Galbraith, J. 1973. Economics & The Public Purpose. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Giridharadas, A. 2006. “Not Everyone Is Grateful as Investors Build Free Apartments in

Mumbai Slums.” New York Times, December 14.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/15/business/worldbusiness/15slums.html?_r=1&oref=s

login.

Gore, A. 2006. An Inconvenient Truth. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press.

Grossman, R., and F. Adams. 1993. Taking Care of Business: Citizenship and the Charter of

Incorporation. Cambridge, MA: Charter, Ink.

Harris, B. 1999. Steal This Book and Get Life Without Parole. Monroe, ME: Common Courage

Press.

Hegel, G. 1988. Introduction to the Philosophy of History. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Hinkley, R. 2002. “How Corporate Law Inhibits Ethics.” Business Ethics. January/February.

Kelly, M. 2003. The Divine Right of Capital: Dethroning the Corporate Aristocracy. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Kidder, R. 2005. Moral Courage. New York: W. Morrow.

35

Kohn, A. 1992. No Contest: The Case Against Competition revised ed. New York: Houghton

Mifflin.

Korten, D. 1995. When Corporations Rule the World. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers,

Inc.

Leadbeater, C. 1997. The Rise of the Social Entrepreneur. London: Demos.Mair, J. and I. Marti.

2006. “Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and

Delight.” Journal of World Business, 41:36-44.

Mair, J., J. Robinson, and K. Hockerts. 2006. “Introduction.” In J. Mair, J. Robinson and K.

Hockerts (Eds.), Social Entrepreneurship. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Marketplace. 2007. “Wall Street Donates Its Wisdom.” http://marketplace.publicradio.org.

November 2.

McFall, L. 1987. “Integrity.” Ethics (98). 5-20.

Muller, J. 1993. Adam Smith in His Time and Ours: Designing the Decent Society. New York:

The Free Press.

Nace, T. 2003. Gangs of America: The Rise of Corporate Power and the Disabling of

Democracy. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Nicholls, A. 2004. “Social Entrepreneurship: The Emerging Landscape.” In S. Crainer and D.

Dearlove (Eds.), Financial Times Handbook of Management, 3

rd

ed. Harlow, UK: FT

Prentice-Hall.

Nicholls, A. 2006. “Introduction.” In A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of

Sustainable Social Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nicholls, A. and A. Cho. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: The Structuration of a Field.” In A.

Nicholls (Ed.), Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nisbet, R. 1994. The Sociological Tradition. New Brunswick, CT: Transaction Publishers.

Oliver, C. 1991. “Strategic Response to Institutional Processes.” Academy of Management

Review, 16(1). 145-179.

Rest, J. 1994. “Background: Theory and Research.” In J. R. Rest and D. Narváez (Eds.), Moral

Development in the Professions. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,

Publishers.

Schumpeter, J. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Shepard, J. 2005. Sociology 9

th

ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Shepard, J., Shepard, J., Wimbush, J., & Stephens, C. 1995. “The Place of Ethics in Business:

Shifting Paradigms?” Business Ethics Quarterly (5). 577-601.

Shulman, B. 2003. The Betrayal of Work: How Low-Wage Jobs Fail 30 Million Americans and

their Families. New York: The New Press.

Skoll Foundation. 2005. www.skollfoundation.org.

Smith, A. 1776/1986. The Wealth of Nations.. In R. L. Heilbroner (Ed.), The Essential Adam

Smith. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Stevenson, H. 1985. “The Heart of Entrepreneurship.” Harvard Business Review, 85-94.

Stone, C. 1975. Where the Law Ends: The Social Control of Corporate Behavior. New York:

Harper Torchbooks.

Suchman, M.1995. “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches.” Academy of

Management Review, 20 (3) 571-610.

36

Turner, B. 1996. Preface to the Second Edition. In E. Durkheim (Author), Professional Ethics

and Civic Morals. London: Routledge.

Van Til, J. 1988. Mapping the Third World: Voluntarism in a Changing Social Economy. New

York: Foundation Centre.

VanSandt, C. 2002. “A Structural Explanation for Unethical Business Practices.” Unpublished

manuscript.

Venkataraman, S. 1997. “The Distinctive Domain of Entrepreneurship Research: An Editor’s

Perspective. In J. Katz and R. Brockhaus (Eds.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm

Emergence and Growth Vol. 3. 119-138. Greenwhich, CT: Jai Press.

Victor, B., & Stephens, C. 1994. “The Dark Side of the New Organizational Forms: An Editorial

Essay.” Organizational Science (5). 479-482.

Walzer, M. 1983. Spheres of Justice: A Defense of Pluralism and Equality. United States: Basic

Books.

Weber, M. 1904-05/1958. The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism. New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons.

Wolman, W., and Colamosca, A. 1997. The Judas Economy: The Triumph of Capital and the

Betrayal of Work. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.

37

Moral

Pressures

Organizational

Legitimacy

Pressures

Isomorphic

Pressures

Political

Pressures

Structural

Pressures

Social

Entrepreneurship

Scaling Up

Scaling Up

Moral

Pressures

Organizational

Legitimacy

Pressures

Isomorphic

Pressures

Political

Pressures

Structural

Pressures

Social

Entrepreneurship

Scaling Up

Scaling Up

38