The impact of disinformation

on democratic processes and

human rights in the world

@Adobe Stock

Authors:

Carme COLOMINA, Héctor SÁNCHEZ MARGALEF, Richard YOUNGS

European Parliament coordinator:

Policy Department for External Relations

Directorate General for External Policies of the Union

PE 653.635 - April 2021

EN

STUDY

Requested by the DROI subcommittee

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT

EP/EXPO/DROI/FWC/2019-01/LOT6/R/02 EN

April 2021 - PE 653.635 © European Union, 2021

STUDY

The impact of disinformation on

democratic processes and human rights

in the world

ABSTRACT

Around the world, disinformation is spreading and becoming a more complex

phenomenon based on emerging techniques of deception. Disinformation

undermines human rights and many elements of good quality democracy; but

counter-disinformation measures can also have a prejudicial impact on human rights

and democracy. COVID-19 compounds both these dynamics and has unleashed more

intense waves of disinformation, allied to human rights and democracy setbacks.

Effective responses to disinformation are needed at multiple levels, including formal

laws and regulations, corporate measures and civil society action. While the EU has

begun to tackle disinformation in its external actions, it has scope to place greater

stress on the human rights dimension of this challenge. In doing so, the EU can draw

upon best practice examples from around the world that tackle disinformation

through a human rights lens. This study proposes steps the EU can take to build

counter-disinformation more seamlessly into its global human rights and democracy

policies.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

ISBN: 978-92-846-8014-6 (pdf) ISBN: 978-92-846-8015-3 (paper)

doi:10.2861/59161 (pdf) doi:10.2861/677679 (paper)

Catalogue number: QA-02-21-559-EN-N (pdf) Catalogue number: QA-02-21-559-EN-C (paper)

AUTHORS

• Carme COLOMINA, Research Fellow, Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB), Spain

• Héctor SÁNCHEZ MARGALEF, Researcher, Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB), Spain

• Richard YOUNGS, Senior Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

• Academic reviewer: Kate JONES, Associate Fellow, Chatham House; Faculty of Law, University of Oxford,

United Kingdom

PROJECT

COORDINATOR (CONTRACTOR)

• Trans European Policy Studies Association (TEPSA)

This study was originally requested by the European Parliament's Subcommittee on Human Rights.

The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the author(s), and any opinions expressed herein do

not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

CONTACTS

IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

Coordination: Marika LERCH, Policy Department for External Policies

Editorial assistant: Daniela ADORNA DIAZ

Feedback is welcome. Please write to marika.lerch@europarl.europa.eu

To obtain copies, please send a request to poldep-expo@europarl.europa.eu

VERSION

English-language manuscript completed on 22 April 2021.

COPYRIGHT

Brussels © European Union, 2021

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

This paper will be published on the European Parliament's online database, '

Think Tank'

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

Table of contents

Executive Summary v

1 Introduction and methodology 1

2 Understanding the concept of disinformation 2

2.1 Definition of disinformation 3

2.2 Instigators and Agents of disinformation 6

2.3 Tools and tactics 6

2.4 Motivations for disinformation 8

3 The impacts of disinformation and

counter-disinformation measures on human rights and

democracy 9

3.1 Impacts on human rights 10

3.1.1 Right to freedom of thought and the right to hold opinions

without interference 10

3.1.2 The right to privacy 10

3.1.3 The right to freedom of expression 11

3.1.4 Economic, social and cultural rights 12

3.2 Impact on democratic processes 13

3.2.1 Weakening of trust in democratic institutions and society 13

3.2.2 The right to participate in public affairs and election

interference 14

3.3 Digital violence and repression 15

3.4 Counter-disinformation risks 16

4 The impact of disinformation during the COVID-19 crisis 18

4.1 Acceleration of existing trends 21

4.2 The impact of the COVID-19 infodemia on Human Rights 21

5 Mapping responses: Legislative and regulatory bodies,

corporate activities and civil society 23

5.1 Legislative and regulatory bodies 25

5.2 Corporate activities 26

5.3 Civil Society 29

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

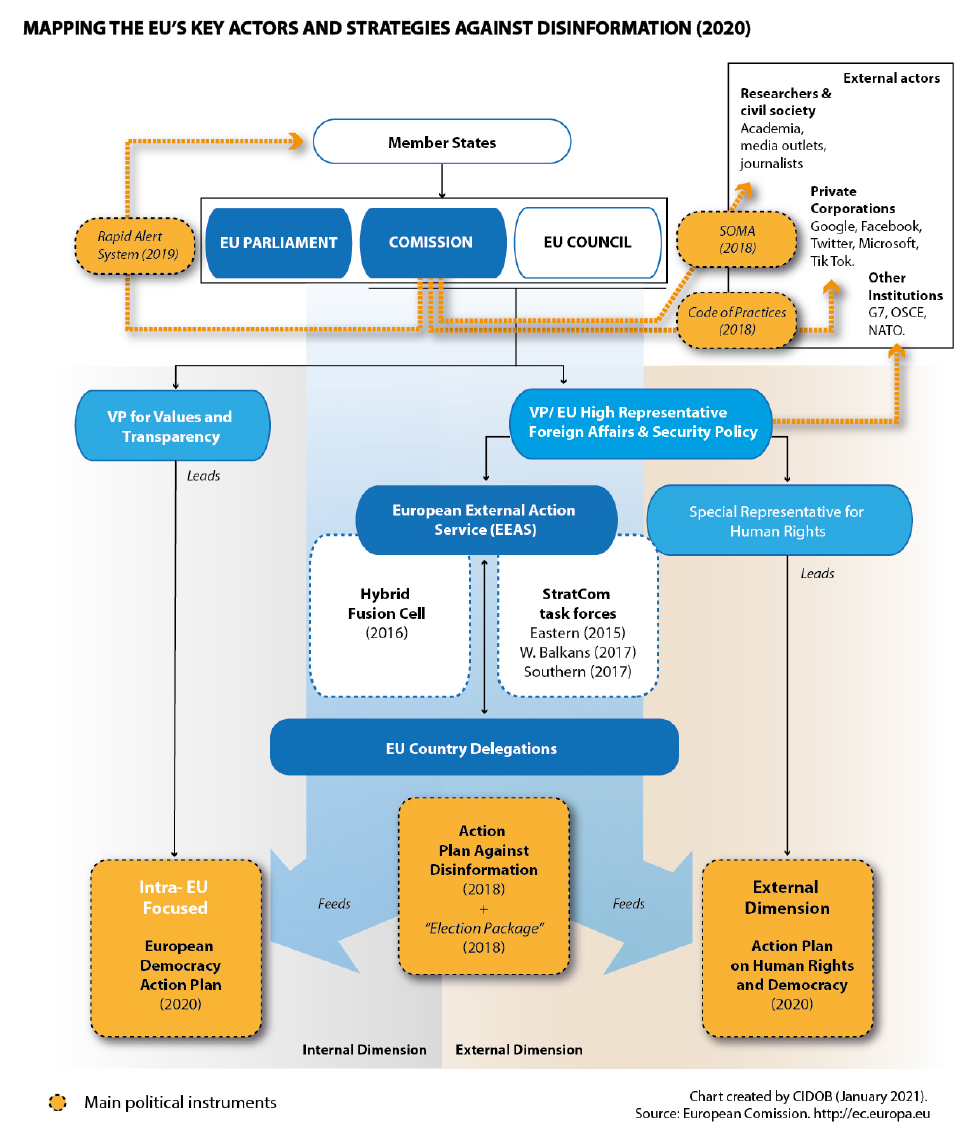

6 EU responses to disinformation 29

6.1 The EU’s policy framework and instruments focusing on

disinformation and European democracy 31

6.1.1 The EEAS Strategic Communication Division 31

6.1.2 The Rapid Alert System 32

6.1.3 The Action Plan Against Disinformation and the Code of

Practice on Disinformation 32

6.1.4 The European Digital Media Observatory 33

6.1.5 The European Democracy Action Plan and the Digital

Services Act 33

6.2 Key elements of the EU’s external Human Rights and

Democracy Toolbox 33

6.2.1 EU human rights guidelines 33

6.2.2 EU engagement with civil society and human rights

dialogues 34

6.2.3 Election observation and democracy support 34

6.2.4 The Action Plan for Human Rights and Democracy for

2020-2024 and funding tools 35

6.2.5 Restrictive measures 36

6.3 The European Parliament’s role 37

7 Rights-based initiatives against disinformation:

identifying best practices 39

7.1 Government and parliamentary responses 39

7.2 Civil society pathways 42

7.2.1 Middle East and North Africa 43

7.2.2 Asia 43

7.2.3 Eastern Europe 43

7.2.4 Latin America 44

7.2.5 Africa 44

7.2.6 Multi-regional projects 44

8 Conclusions and recommendations 46

8.1 Empowering Societies against Disinformation 47

8.1.1 Supporting local initiatives addressing disinformation 48

8.1.2 Enhancing support to media pluralism within

disinformation strategies 48

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

iv

Acronyms and Abbreviations

CoE Council of Europe

CSO Civil Society Organisations

DEVCO Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development

EDAP European Democracy Action Plan

EDMO European Digital Media Observatory

EP European Parliament

EU European Union

HLEG High Level Group of Experts on Fake News and Online Disinformation

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

PACE Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

UDHR Universal Declaration on Human Rights

UN United Nations

UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council

WHO World Health Organization

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

v

Executive Summary

The concept of disinformation refers to false, inaccurate or misleading information designed, presented

and promoted intentionally to cause public harm or make a profit. Around the world, disinformation is

spreading and becoming a more complex trend based on emerging techniques of deception. Hence, it needs

to be understood today as being nested within countless techniques from manipulative information strategies.

This reflects the acceleration of deep-fake technology, increasingly sophisticated micro-targeted

disinformation campaigns and more varied influence operations. In its external relations, the EU needs

comprehensive and flexible policy instruments as well as political commitment to deal more effectively

with this spiralling phenomenon.

Disinformation also has far-reaching implications for human rights and democratic norms worldwide. It

threatens freedom of thought, the right to privacy and the right to democratic participation, as well as

endangering a range of economic, social and cultural rights. It also diminishes broader indicators of

democratic quality, unsettling citizens’ faith in democratic institutions not only by distorting free and fair

elections, but also fomenting digital violence and repression. At the same time, as governments and

corporations begin to confront this issue more seriously, it is apparent that many of their counter-

disinformation initiatives also sit uneasily with human rights and democratic standards. Disinformation

undermines human rights and many elements of good democratic practice; but counter-disinformation

measures can also have a prejudicial impact on human rights and democracy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these trends and problems. It has unleashed new, more intense

and increasingly varied disinformation campaigns around the world. Many non-democratic regimes have

made use of the pandemic to crack down on political opposition by restricting freedom of expression and

freedom of the media. COVID-19 compounds both disinformation’s threat to international human rights, on

the one hand, and the dangers of counter-disinformation serving anti-democratic agendas, on the other.

Effective responses to disinformation are needed at different levels, embracing formal legal measures and

regulations, corporate commitments and civil society action. In many countries, legislative and executive

bodies have moved to regulate the spread of disinformation. They have done so by elaborating codes of

practice and guidelines, as well as by setting up verification networks to debunk disinformation. Some

corporations have also launched initiatives to contain disinformation, although most have been

ambivalent and slow in their efforts. Civil society is increasingly being mobilised around the world to fight

against disinformation and often does so through a primary focus on human rights and building

democratic capacity at the local level.

The EU needs to support counter-disinformation efforts in its external relations as a means of protecting

human rights, making sure it does not support moves that actually worsen human rights. European

institutions have begun to develop a series of instruments to fight disinformation, both internally and

externally. Having promised a human rights approach in its internal actions, the EU has also formally

recognised the need to build stronger human rights and democracy considerations into its external actions

against disinformation and deceptive influence strategies. The EU’s policy instruments have improved in

this regard over recent years, with numerous concrete examples of EU initiatives that adopt a human-rights

approach to counter disinformation in third countries.

There is a growing number of practical examples from around the world that offer best practice templates

for how the counter-disinformation and human rights agendas can not only be aligned with each other

but also be mutually reinforcing. Such examples offer valuable reference points and provide guidance on

ways through which the EU should direct its counter-disinformation efforts, in tandem with external

support, so as to pursue human rights and democracy. These emergent practices highlight the importance

of collaboration between European institutions and civil society as the indispensable basis for building

societal resilience to disinformation.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

vi

While the EU has begun to tackle disinformation in its external actions, it can and should place greater stress on

the human rights dimension within this challenge. Despite the progress made in recent years, EU efforts to

tackle disinformation globally need to dovetail seamlessly into the EU’s overarching approach towards

human rights internationally. The EU has tended to approach disinformation as a geopolitical challenge,

to the extent that other powers use deception strategies against the Union itself, but much less as a human-

rights problem within third countries. It still seeks to deepen security relations with many regimes guilty of

using disinformation to abuse the rights and freedoms of their own citizens.

The EU can take a number of steps to rectify prevailing shortcomings, working at different levels of the

disinformation challenge.

• Adopt further measures to exert rights-based external pressure both over corporations and third-

country governments.

• Step up efforts to empower third country societies in the fight against disinformation.

• Foster new forms of global dialogue that fuse together disinformation and human rights concerns.

This report details how the EP can play a key role at each level of these recommendations.

• In its ongoing efforts with other parliaments around the world to strengthen global standards, it can

push for a UN Convention on Universal Digital (Human) Rights, working together with legislatures from

like-minded countries.

• Using these relationships with other parliaments along with its special committee on Foreign

Interference in all Democratic Processes in the EU including Disinformation (INGE), the EP should

promote best practices with third countries, emphasising the centrality of parliamentary accountability

in countering disinformation.

• The Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy 2020-24 stresses support to parliamentary

institutions, thereby offering the EP a reference point and platform from which to exert stronger

influence over implementation of the EU’s external toolbox, thus ensuring that this gives adequate

protection inter alia to human rights in the fight against disinformation.

• The EP can do more to push for increased funding to projects aimed at counteracting disinformation

from a human rights perspective.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

1

1 Introduction and methodology

This study considers the impact of online disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in

countries outside the European Union. The scope of analysis is limited to legal content shared online; illegal

content poses very different political and legal considerations. The study explores both the human rights

breaches caused by disinformation as well as those caused by laws and actions aimed at tackling this

phenomenon. Our research covered both EU institutional and civil society perspectives in detail.

The study analyses how the EU can better equip itself to tackle disinformation worldwide while protecting

human rights. It explores public and private initiatives in third countries, identifying best practices of rights-

based initiatives. Special attention is given to recent and current EU proposals, actions and instruments of

significant relevance to tackling disinformation in third countries.

Our research methodology included a systematic desk-review of the existing literature on disinformation,

human rights and democracy, relying on four types of sources: official documents, communication from

stakeholders, scholarly literature and press articles. This study builds from the research published by

international organisations, like UNESCO and the Council of Europe, and human rights resolutions from

international bodies, including the UN Human Rights Council.

A series of semi-structured interviews were conducted between September 2020 and January 2021. The

interviews were conducted under Chatham House rule, meaning that interviewees’ comments are taken

into account but not attributed in this report. The interviewees included staff members from several

divisions of the European External Action Service (EEAS) – including its StratCom unit – and representatives

from the Directorate General for International Cooperation (DEVCO, now the DG for International

Partnerships, INTPA), as well as MEPs representing different political groups within the European

Parliament. We prioritised MEPs who are members of the Subcommittee on Human Rights (DROI) or, in

their absence, members of the Special Committee on Foreign Interference in All Democratic Processes

within the EU, Including Disinformation (INGE) or Members from the Committee on Foreign Affairs (AFET),

respecting gender balance at all times. The authors contacted more than one MEP per group, but the ratio

of responses was low. Nonetheless, interviews were conducted with one MEP for each political group

except for MEPs from the Identity and Democracy Group (ID), which did not respond to our request.

Members from the Non-attached group (NI) were not contacted

1

. The authors would like to thank all the

interviewees for their kind contributions.

Moreover, input was collected from civil society organisations through the European Endowment for

Democracy (EED). The methodology sought to reflect the equal importance of formal institutional

approaches and civil society responses to disinformation. The selection of best practices draws on a global

civil society research project coordinated by one of the authors, which took place over the four years

previous to this study. The project engaged with human rights defenders from all regions of the world who

are active on these issues. This research project includes original fieldwork and empirical studies

2

.

1

Interview with an MEP from the European People’s Party sitting in the Subcommittee on Human Rights on the 23rd of October,

2020; interview with an MEP from the Socialist and Democrats sitting in the Subcommittee on Human Rights and the Committee

on Foreign Affairs on the 5th of October 2020; interview with an MEP from the Renew group sitting in the Committee on Foreign

Affairs on the 17th of December 2020; interview with an MEP from the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance sitting in the

Subcommittee on Human Rights and the Committee on Foreign Affairs on the 14th of January 2021; interview with an MEP from

the European Conservatives and Reformists Group sitting in the Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic

Processes in the European Union, including Disinformation on the 12th of January 2021; and interview with an MEP from the Left

Group sitting in the Committee on Foreign Affairs on the 29th of October 2020. MEPs represented a total of six political groups out

of eight, with three women and three men interviewed.

2

Carnegie’s Civic Research Network is a global group of leading experts and activists dedicated to examining the changing patterns

of civic activism around the world.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

2

2 Understanding the concept of disinformation

‘

How can we make sense of democratic values in a world of

digital disinformation run amok? What does freedom of speech

mean in an age of trolls, bots, and information war? Do we

really have to sacrifice freedom to save democracy

—

or is there

another way?

’

Peter Pomerantsev, Agora Institute, John Hopkins

University and London School of Economics

3

Key takeaways

• The concept of disinformation refers to false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed,

presented and promoted intentionally to cause public harm or make a profit.

• Disinformation has spread rapidly with the rise of social media. Over 40 % of people surveyed in

different regions of the world are concerned that it has caused increased polarisation and more foreign

interference in politics.

• Disinformation can confuse and manipulate citizens; create distrust in international norms, institutions

or democratically agreed strategies; disrupt elections; or feed disbelief in key challenges such as climate

change.

• The more this phenomenon expands globally and the more multi-faceted it becomes, the more

necessary it is to address not only the content dimension of disinformation but simultaneously the

tactics of manipulative influence that accompany it. It is also important to understand the motivations

for disinformation – political, financial or reputational (to build influence) – so that these can be

addressed.

The internet has provided unprecedented amounts of information to huge numbers of people worldwide.

However, at the same time, false, trivial and decontextualised information has also been disseminated. In

providing more direct access to content, less mediated by professional journalism, digital platforms have

replaced editorial decisions with engagement-optimising algorithms that prioritise clickbait content

4

.

Social networks have transformed our personal exposure to information, persuasion and emotive imagery

of all kinds.

In recent years, the transmission of disinformation has increased dramatically across the world. While

providing for a plurality of voices, a democratisation of access to information and a powerful tool for

activism, the internet has also created new technological vulnerabilities. An MIT Media Lab research found

that lies disseminate ‘farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth’ and falsehoods were ‘70 %

more likely to be retweeted than the truth’

5

. False content has potentially damaging impacts on core

3

Annenberg Public Policy Center

,

Freedom and Accountability: A Transatlantic Framework for Moderating Speech Online

,

Final

Report of the Transatlantic High Level Working Group on Content Moderation Online and Freedom of Expression, June 2020.

4

Karen Kornbluh and Ellen P. Goodman, Safeguarding Digital Democracy. Digital Innovation and Democracy Initiative Roadmap

,

The German Marshall Fund of the United States DIDI Roadmap n 4, March 2020.

5

Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy and Sinan Aral, The spread of true and false news online. Science, vol 359(6380), 2018, pp 1146-

1151.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

3

human rights and even the functioning of democracy. Disinformation can serve to confuse or manipulate

citizens; create distrust in international norms, institutions or democratically agreed strategies; disrupt

elections; or fuel disbelief in key challenges such as climate change

6

.

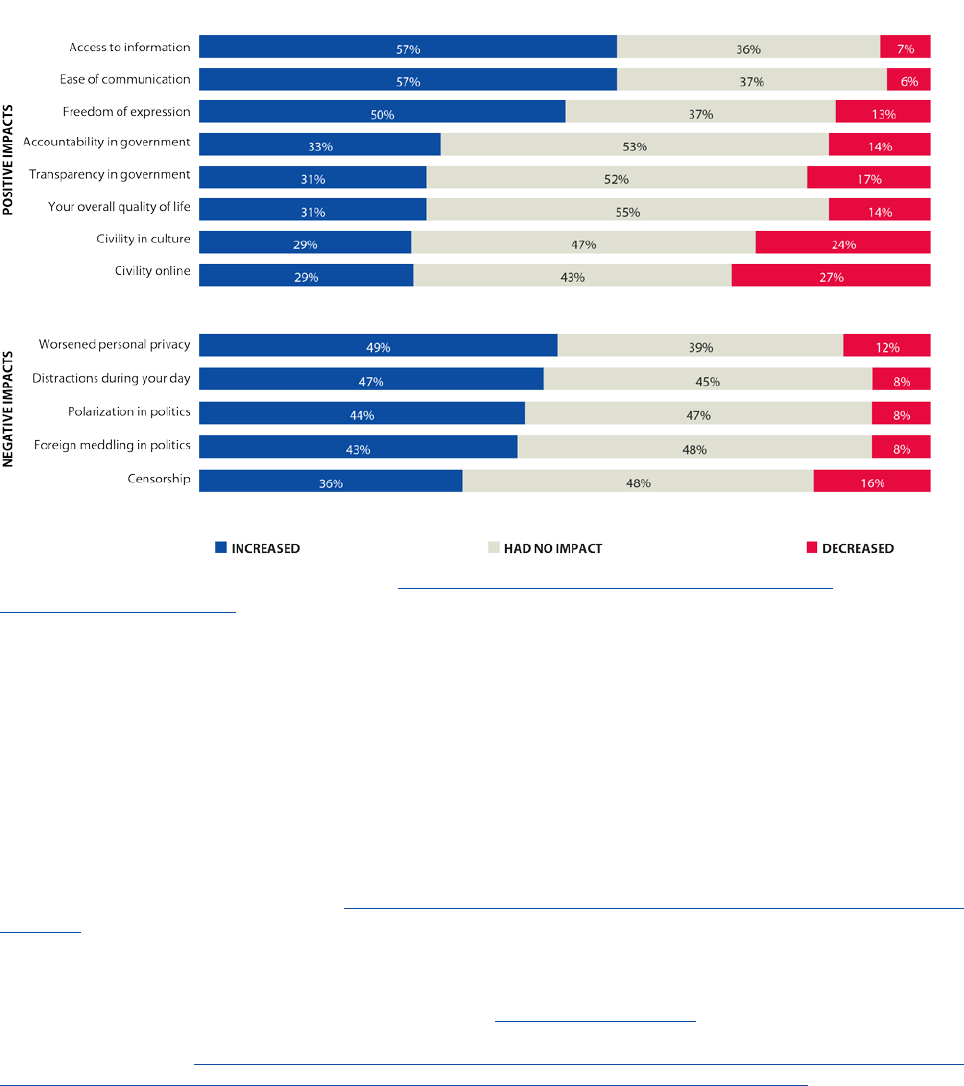

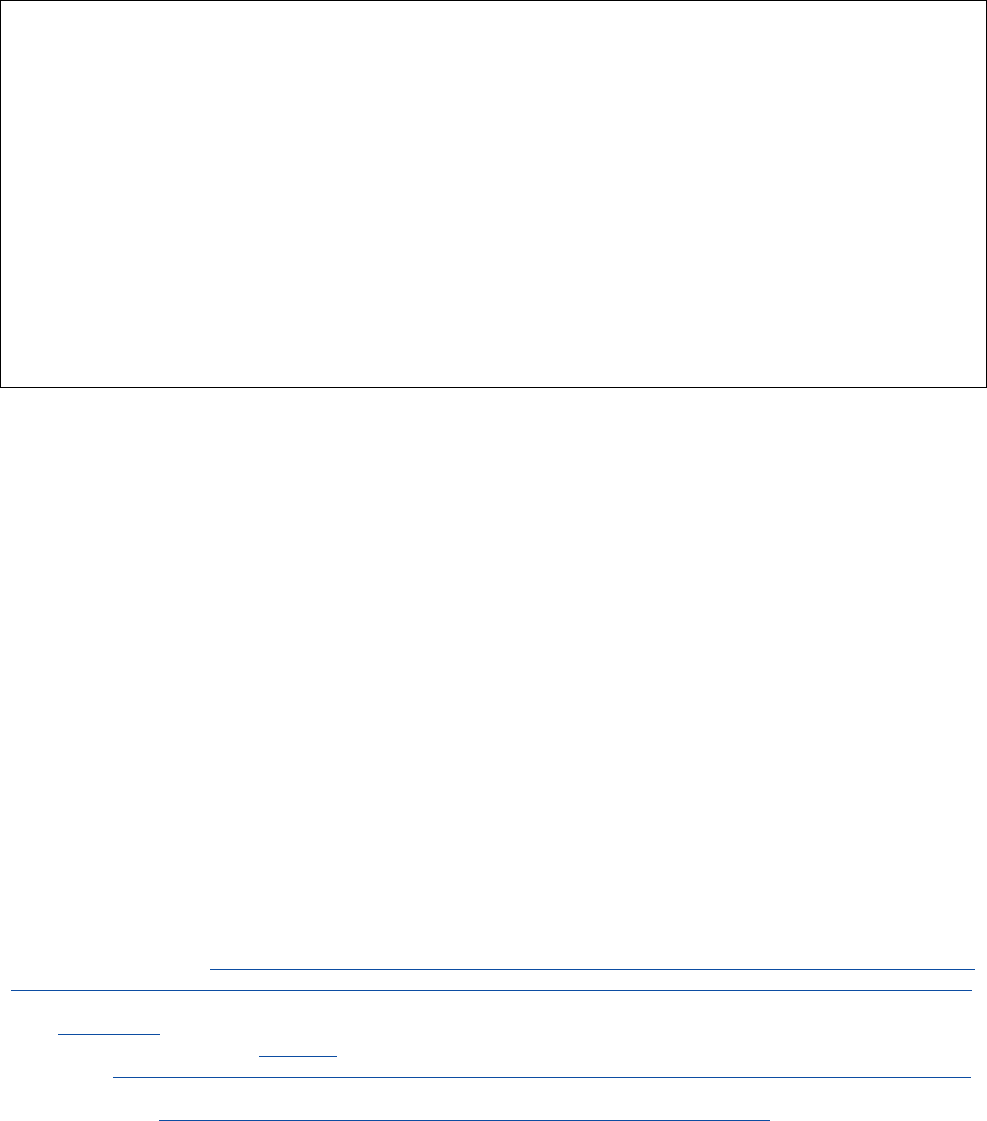

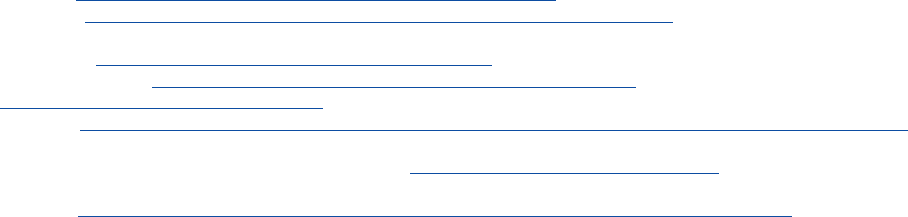

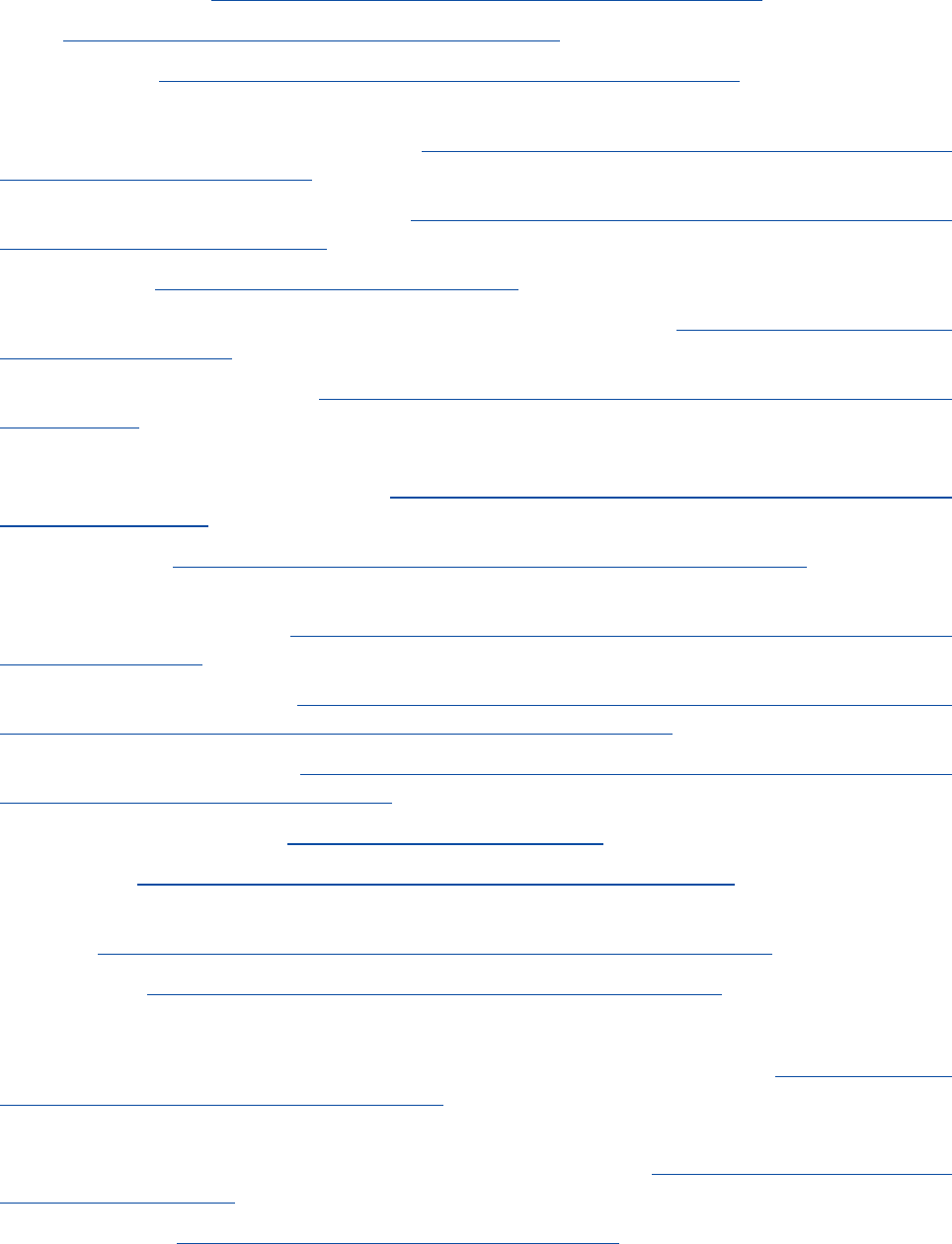

The graph below (Figure 1), on public perceptions of the impact of digital platforms, presents the results

of interviews with over 1 000 people in 25 countries in late 2018 and early 2019. It shows that over 50 % of

people considered that whilst social media had increased their ability to communicate and access

information, they had mixed feelings about the impact on inter-personal relations. Over 40 % of people

perceived that social media had contributed to both polarisation and foreign meddling in politics.

Figure 1. The impact of digital platforms: public perceptions

7

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on CIGI-Ipsos, 2019 CIGI-Ipsos Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust., 2019; CIGI-Ipsos,

Internet security and Trust. Part 3, 2019.

2.1 Definition of disinformation

For the European Union, the concept of disinformation refers to ‘verifiably false or misleading information

that is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally deceive the public and

may cause public harm’

8

. A similar definition was also adopted by the Report of the independent High-

6

Kalina Bontcheva and Julie Posetti (eds.), Balancing Act: Countering Digital Disinformation While Respecting Freedom of

Expression, UNESCO Broadband Commission Report, September 2020.

7

The percentage refers to people interviewed in 25 different countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany,

Great Britain, Hong Kong (China), India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, South Africa,

Republic of Korea, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey and the United States) accounting for 1.000+ individuals in each country during

December 2018 and February 2019: See the original source (CIGI IPSOS Global Survey) for more information about the

methodology employed.

8

European Commission, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on Action Plan against Disinformation, JOIN(2018) 36 final,

December 2018.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

4

Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation published in March 2018

9

. Under this definition, the

risk of harm includes threats to democratic political processes and values. The production and promotion

of disinformation can be motivated by economic factors, reputational goals or political and ideological

agendas. It can be exacerbated by the ways in which different audiences and communities receive, engage

and amplify disinformation

10

. This definition is in line with the one adopted in a note produced by the

European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) in 2015

11

.

The authors of Disinformation and propaganda

–

impact on the functioning of the rule of law in the EU and its

Member States

12

use the terms ‘disinformation’ and ‘propaganda’ to describe phenomena characterised by

four features, namely that: is ‘designed to be false or manipulated or misleading (disinformation) or is

content using unethical persuasion techniques (propaganda); has the intention of generating insecurity,

tearing cohesion or inciting hostility, or directly to disrupt democratic processes; is on a topic of public

interest; and often uses automated dissemination techniques to amplify the effect of the communication’.

Immediately after the 2016 US election, concepts such as ‘alternative facts’, ‘post-truth’ and ‘fake news’

entered into public discourse. Even though the term ‘fake news’ emerged around the end of the 19th

century, it has become too vague and ambiguous to capture the essence of disinformation. Since the term

‘fake news’ is commonly used as a weapon to discredit the media, experts have called for this term to be

abandoned altogether in favour of more precise terminology

13

. The High-Level Group on Fake News and

Online Disinformation also took the view that ‘fake news’ is an inadequate term, not least because

politicians use it self-servingly to dismiss prejudicial coverage

14

.

Wardle and Derakhshan categorise three types of information disorders to differentiate between messages

that are true and those that are false, as well as determining which are created, produced, or distributed

by ‘agents’ who intend to do harm and those that are not

15

. These three types of information disorders –

dis-information, mis-information and mal-information – are illustrated in Table 1. The intention to harm or

profit is the key distinction between disinformation and other false or erroneous content.

9

Here, disinformation refers to false, inaccurate or misleading information designed, presented and promoted intentionally to

cause public harm or make a profit. See Independent High level Group on fake news and online disinformation, A multi-

dimensional approach to disinformation, Report for the European Commission, March 2018.

10

Independent High level Group on fake news and online disinformation, March 2018.

11

Authors' note: The European Parliamentary Research Service, in its 2015 At a glance paper, used the Oxford English Dictionary’s

definition of disinformation: ‘dissemination of deliberately false information, especially when supplied by a government or its

agent to a foreign power or to the media, with the intention of influencing the policies or opinions of those who receive it; false

information so supplied’. It also acknowledged that in some official communications, the European Parliament has used the term

propaganda when referring to Russia’s disinformation campaigns or even misinformation, although there is consensus that

misinformation happens unintentionally.

12

Judit Bayer, Natalija Bitiukova, Petra Bárd, Judit Szakács, Alberto Alemanno and Erik Uszkiewicz, ‘Disinformation and propaganda

– impact on the functioning of the rule of law in the EU and its Member States’, Directorate General for Internal Policies of the

Union (IPOL), European Parliament, 2019.

13

Margaret Sullivan, It’s Time To Retire the Tainted Term Fake News, Washington Post, 6 January 2017. [Accessed on 26 March 2021].

14

Independent High level Group on fake news and online disinformation, A multi-dimensional approach to disinformation, Report

for the European Commission, March 2018.

15

Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy

making, Council of Europe report DGI(2017)09, 2017.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

5

Table 1. Types of Information Disorders

Definition

Example

Misinformation

When

false information

is shared, but no harm is

meant

A terror attack on the Champs Elysees on 20 April

2017 generated a great amount of misinformation in

social networks, spreading rumours and unconfirmed

information

16

. People sharing that kind of

information didn't mean to cause harm.

Disinformation

When false information

is knowingly shared to

cause harm

During the 2017 French presidential elections, a

duplicate version of the Belgian newspaper Le Soir

was created, with a false article claiming that

Emmanuel Macron was being funded by Saudi

Arabia

17

.

Malinformation

When

genuine

information is shared to

cause harm

The intentional leakage of a politician’s private

emails, as happened during the presidential elections

in France 2017

18

.

Source and examples: Wardle and Derakhshan, Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy

making, Council of Europe report DGI(2017)09, 2017.

The challenge posed by disinformation comes not only from its content, but also how it is distributed and

promoted on social media. The intention to harm or profit that characterises disinformation itself entails

that disinformation is commonly accompanied by strategies and techniques to maximise its influence.

Hence, the European Democracy Action Plan

19

– the European Commission’s agenda to strengthen the

resilience of EU democracies – broadens the discussion from tackling disinformation to also tackling

‘information influence operations’ and ‘foreign interference in the information space’. Both these concepts

encompass coordinated efforts to influence a targeted audience by deceptive means, the latter involving

a foreign state actor or its agents. EU external strategies need to respond not only to the challenge of

disinformation, but to these deceptive influence strategies more broadly.

Social media platforms are already tackling these challenges of influence to some extent. For instance,

Facebook tackles ’coordinated inauthentic behaviour’, understood as ‘coordinated efforts to manipulate

public debate for a strategic goal where fake accounts are central to the operation’

20

. Twitter’s ‘platform

manipulation’ refers to the ‘unauthorised use of Twitter to mislead others and/or disrupt their experience

by engaging in bulk, aggressive, or deceptive activity’

21

. Similarly, Google reports on ‘coordinated influence

operation campaigns’

22

.

16

One example of this, mentioned by Wardle and Derakhshan (2017), was the rumour that Muslim population in the UK had

celebrated the attack. This was debunked by CrossCheck. For more information on the role of social media that night, also read

Soren Seelow ‘Attentat des Champs-Elysées : le rôle trouble des réseaux sociaux’, in Le Monde, 4 May 2017.

17

EU vs. Disinfo, ‘EMMANUEL MACRON’S CAMPAIGN HAS BEEN FUNDED BY SAUDI ARABIA, SINCE…’, published on 2 February

2017. [Accessed on 11 February 2021].

18

Meghan Mohan, Macron Leaks: the anatomy of a hack, BBC, published on 9 May 2017. [Accessed on 11 February 2021]

19

European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic

and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the European Democracy Action Plan, COM (2020) 790 final,

December 2020.

20

Facebook, December 2020 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report, January 2021. [Accessed on 11 February 2021].

21

Twitter Transparency Center, Platform Manipulation, January – June 2020, January 2021.

22

Shane Huntley, Updates about government-backed hacking and disinformation, Google Threat Analysis Group, May 2020.

[Accessed on 11 February 2021]

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

6

2.2 Instigators and Agents of disinformation

Anyone with a social media account can create and spread disinformation: governments, companies, other

interest groups, or individuals. When analysing the different actors responsible for disinformation, the

UNESCO Working Group on Freedom of Expression and Addressing Disinformation makes a distinction

between those fabricating disinformation and those distributing content: the instigators (direct or indirect)

are those creating the content and the agents (‘influencers’, individuals, officials, groups, companies,

institutions) are those in charge of spreading the falsehoods

23

.

The most systemic threats to political processes and human rights arise from organised attempts to run

coordinated campaigns across multiple social media platforms. As indicated by Facebook’s exposure of

coordinated inauthentic behaviour, large disinformation campaigns are often linked with governments,

political parties and the military, and/or with consultancy firms working for those bodies

24

. When the

instigator or agent of disinformation is – or has the backing of – a foreign state it may be breaching the

public international law principle of non-intervention

25

. Experts consider that the principle of non-

intervention applies as much to a state’s cyber operations as it does to other state activities. Foreign

interference should be understood as the ‘coercive, deceptive and/or non-transparent effort to disrupt the

free formation and expression of individuals’ political will by a foreign state actor or its agents’

26

. Since

exposure of the role of Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) – considered a ‘troll farm’ spreading pro-

Kremlin propaganda online under fake identities – in US politics in 2016, concerns have grown over foreign

interference operations involving disinformation. Civil society monitoring indicates that an increasingly

assertive China has joined Russia in interfering in democratic processes abroad

27

. This includes interference

in elections through concerted disinformation campaigns, fostering democratic regression and promoting

‘authoritarian resurgence’

28

. An EEAS special report published in April 2020 noted that ‘state-backed

sources from various governments, including Russia and – to a lesser extent – China, have continued to

widely target conspiracy narratives and disinformation both at public audiences in the EU and the wider

neighbourhood’

29

.

2.3 Tools and tactics

Disinformation campaigns are becoming increasingly sophisticated and micro-targeted, through

marketing strategies that use people’s data to segment them into small groups, thus providing apparently

tailored content. The fact that content sharing has also moved from open to encrypted platforms

(WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and WeChat are in the top five social media platforms globally) makes it

more difficult to track disinformation.

23

Kalina Bontcheva and Julie Posetti (eds.), Balancing Act: Countering Digital Disinformation While Respecting Freedom of

Expression, UNESCO Broadband Commission Report, September 2020.

24

Nathaniel Gleicher, Removing Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior, Facebook, published on 8 July 2021. [Accessed on 11 February

2021]

25

Carolyn Dubay, A Refresher on the Principle of Non-Intervention, International Judicial Monitor, Spring Issue, 2014.

26

James Pamment, The EU’s Role in Fighting Disinformation: Crafting A Disinformation Framework, Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace Future Threats Future Solutions series, n 2, September 2020

https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/09/24/eu-s-role-in-fighting-disinformation-crafting-disinformation-framework-pub-82720

27

European Partnership for Democracy (EPD), Louder than words? Connecting the dots of European democracy support. 2019.

28

Larry Diamond, The Democratic Rollback. The Resurgence of the Predatory State, Foreign Affairs, 87(2), 2008, pp 36–48.

29

EU vs. Disinfo, EEAS SPECIAL REPORT UPDATE: SHORT ASSESSMENT OF NARRATIVES AND DISINFORMATION AROUND THE

COVID-19/CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC (UPDATED 2 – 22 APRIL), published on 24 April 2020. [Accessed on 11 February 2021]

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

7

Among the emerging tools available to spread disinformation are:

• Manufactured amplification (artificially boosting the reach of information by manipulating search

engine results, promoting hashtags or links on social media)

30

• Bots (social media accounts operated by computer programmes, designed to generate posts or

engage with social platforms’ content)

31

• Astroturf campaigns (masking the real sponsor of a message, giving the false impression that it comes

from genuine grass-roots activism)

• Impersonation of authoritative media, people or governments (through false websites and/or social

media accounts)

• Micro-targeting (using consumer data, especially on social media, to send different information to

different groups

32

. Even if micro-targeting is not necessarily illegal and may be equally used by those

spreading legitimate information, the scandal of Cambridge Analytica demonstrates that it poses a

serious risk regarding the spread of disinformation)

33

• ‘Deep-fakes’ (digitally altered or fabricated videos or audio)

34

There are different state-sponsored disinformation activities that can be considered harmful practices. In

2019, political parties or leaders in around 45 democratic countries used computational propaganda tools

by amassing fake followers to gain voter support; in 26 authoritarian states government entities used

computational propaganda as a tool for information control to suppress public opinion and press freedom

and discredit opposition voices and political dissent

35

.

Manipulation can also be achieved through online selective censorship (removing certain content from a

platform by governments’ demands or by platforms’ curation responses), hacking and sharing or

manipulating search engine results

36

.

In this acceleration of manipulation, deep-fake technology can be harmful because people cannot tell

whether content is genuine or false. Real voices can be manipulated to say things that were never said,

making citizens unable to decipher between fact and fiction. That is why deep-fake technology may pose

particular harm to democratic discourse and to national and individual security. When we can no longer

believe what we see, truth and trust are at risk. Even before entering the political scene, deep-fake

technology had already been used to fabricate pornographic content for criminal purposes, thereby

30

Sam Earle, Trolls, Bots and Fake News: The Mysterious World of Social Media Manipulation, Newsweek, published on 14 October

2017. [Accessed on 11 February 2021]

31

Earle, 2017.

32

Ghosh Dipayan, What Is Microtargeting and what is it doing in our politics, Internet Citizen, Harvard University, 2018.

33

Carole Cadwalladr, as told to Lee Glendinning, Exposing Cambridge Analytica: 'It's been exhausting, exhilarating, and slightly

terrifying, The Guardian, published on 29 September 2018. [Accessed on 11 February 2021]; and Dobber, Tom; Ronan Ó Fathaigh

and Frederik J. Zuiderveen Borgesius,, The regulation of online political micro-targeting in Europe, Journal on internet regulation,

Vol. 8(4), 2019.

34

Beata Martin-Rozumiłowicz and Rasto Kužel, Social Media, Disinformation and Electoral Integrity, International Foundation for

Electoral Systems, Working Paper, August 2019.

35

Samantha Bradshaw and Philip N. Howard, The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media

Manipulation, University of Oxford Working Paper 2019(3), 2019.

36

Judit Bayer, Natalija Bitiukova, Petra Bárd, Judit Szakács, Alberto Alemanno and Erik Uszkiewicz, ‘Disinformation and propaganda

– impact on the functioning of the rule of law in the EU and its Member States’, Directorate General for Internal Policies of the

Union (IPOL), European Parliament, 2019.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

8

posing a tangible human rights threat to women in particular

37

. The Brookings Institute notes that harmful

deep-fakes may impact democratic discourse in three ways

38

:

• Disinformative video and audio: citizens may believe and remember online disinformation, which can

be spread virally through social media.

• Exhaustion of critical thinking: if citizens are unable to know with certainty what news content is true

or false, this will exhaust their critical thinking skills leading to an inability to make informed political

decisions.

• The Liar’s Dividend: politicians will be able to deny responsibility by suggesting that a true audio or

video content is false, even if it is true (in the way that ‘fake news’ has become a way of deflecting media

reporting).

Technology is always one step ahead and brings about a near-future where ‘we will see the rise of

cognitive-emotional conflicts: long-term, tech-driven propaganda aimed at generating political and social

disruptions, influencing perceptions, and spreading deception’ (Pauwels, 2019: 16). Some studies are

already measuring the effects of deep-fakes on people’s political attitudes and proving how microtargeting

amplifies those effects

39

.

2.4 Motivations for disinformation

Research has identified a variety of motivations behind disinformation, including financial or political

interests, state actors’ agendas, trolling and disruption along with even the desire for fame

40

. In some cases,

distorted information does not always seek to convince, but rather to emphasise divisions and erode the

principles of shared trust that should unite societies

41

. Lies breed confusion and contribute to the ‘decay

of truth’

42

and to a clash of narratives. In other cases, disinformation can be a very powerful strategy built

on low-cost, low-risk but high-reward tactics in the hands of hostile actors, feeling less constrained by

ethical or legal principles and offering very effective influence techniques

43

. The proliferation of social

media has democratised the dissemination of such narratives and the high consumption of content

undercutting truthfulness creates the perfect environment for some states to innovate in the old playbook

of propaganda. Financial reward can also provide substantial motivation as almost USD 0.25 billion is spent

in advertising on disinformation sites each year

44

.

Hwang

45

identifies political, financial and reputational incentives. Firstly, political motivation to spread

disinformation can go from advancing certain political agendas (for instance, linking immigration with

criminality) to imposing a narrative that presents a better geopolitical image of certain other nations

(illiberal democracies as an opposite to failing western democracies). Secondly, economic motivation is

37

Madeline Brady, Deepfakes: a new disinformation threat? Democracy Reporting International, August 2020.

38

Alex Engler, Fighting deepfakes when detection fails, The Brookings Institute, Published on 24 November 2019. [Accessed on 11

February 2021].

39

Tom Dobbe, Nadia Metoui, Damian Trilling, Natali Helberger and Claes de Vreese, Do (Microtargeted) Deepfakes Have Real

Effects on Political Attitudes, The International Journal of Press/Politics, Vol 26(1), 2021, pp 69-91.

40

Rebecca Lewis, and Alice Marwick, Taking the Red Pill: Ideological motivations for Spreading Online Disinformation, in

Understanding and Addressing the Disinformation Ecosystem, Annenberg School for Communication, December 2017.

41

Carme Colomina, Techno-multilateralism: The UN in the age of post-truth diplomacy, in Bargués, P., UN@75: Rethinking

multilateralism, CIDOB Report, vol.6, 2020.

42

Jennifer Kavanagh and Michael D. Rich, Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in

American Public Life. RAND Corporation Research Reports, 2018.

43

James Pamment. The EU’s Role in Fighting Disinformation: Crafting A Disinformation Framework, Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace Future Threats Future Solutions series, n 2, September 2020.

44

Global Disinformation Index, The Quarter Billion Dollar Question: How is Disinformation Gaming Ad Tech?, September 2019.

45

Tim Hwang, ‘Digital disinformation: A primer’, Atlantic Council Eurasia Group, September 2017.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

9

linked with social platforms’ economic models that benefit from the ‘click-bait model’, hence attracting

users through content that is tempting, albeit false. Finally, reputational motivation has to do with the

penetration of social networks used in our daily lives. There is an increasing dependence on friends, family

or group endorsement

46

.

3 The impacts of disinformation and counter-disinformation

measures on human rights and democracy

'

…

technology would not advance democracy and human

rights for (and instead of) you'

Zygmunt Bauman in A Chronicle of Crisis: 2011-2016

Key takeaways:

• Online disinformation has an impact on human rights. It affects the right to freedom of thought and the

right to hold opinions without interference; the right to privacy; the right to freedom of expression; the

right to participate in public affairs and vote in elections.

• More broadly, disinformation diminishes the quality of democracy. It saps trust in democratic institutions,

distorts electoral processes and fosters incivility and polarisation online.

• While robust counter-disinformation is needed to protect democracy, it can itself undercut human rights

and democratic quality.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) offers protection to all people in all countries

worldwide, but is not legally binding. Conversely, Human Rights are also secured in a series of treaties, such

as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and International Covenant on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which are legally binding, but do not cover all countries. According to

the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights, states have a duty to protect their population against human

rights violations caused by third parties (Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’

Framework, 2011, Foundational Principles 1). In addition, businesses are required to respect human rights

in their activities (Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework, 2011,

Foundational Principles 11).

This chapter explains the different ways in which disinformation infringes human rights and menaces the

quality of democratic practice. It unpacks precisely which human rights are endangered by disinformation

and which aspects of broader democratic norms it undermines. The chapter then points to an issue that is

of crucial importance for EU actions on this issue in third countries: while disinformation threatens human

rights, the inverse challenge is that counter-disinformation policies can also restrict freedoms and rights.

46

Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy

making, Council of Europe report DGI(2017)09, 2017.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

10

3.1 Impacts on human rights

Freedom of expression is a core value for democracies (Article 19(2) of ICCPR). This includes press freedom

and the right to access information. Under human rights law, even the expression of false content is

protected, albeit with some exceptions.

Digitalisation and global access to social networks have created a new set of channels for the violation of

human rights, which the UN Human Rights Council confirms must apply as much online as they do offline

47

.

Digitalisation has amplified citizens’ vulnerability to hate speech and disinformation, enhancing the

capacity of state and non-state actors to undermine freedom of expression. Looking more closely at various

levels of impact, disinformation threatens a number of human rights and elements of democratic politics

48

.

3.1.1 Right to freedom of thought and the right to hold opinions without

interference

Article 19 of the UDHR states:

‘Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions

without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and

regardless of frontiers.’

Article 19 of ICCPR states:

‘1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive

and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in

the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and

responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are

provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (order public), or of public health or morals.’

In its 2011 General Comment on Article 19 ICCPR, which covers both freedom of opinion and freedom of

expression, the UN Human Rights Committee proclaims that: ‘Freedom of opinion and freedom of

expression are indispensable conditions for the full development of the person. They are essential for any

society. They constitute the foundation stone for every free and democratic society’. Freedom of thought

entails a right not to have one’s opinion unknowingly manipulated or involuntarily influenced. It is not yet

clear where the dividing line is between legitimate political persuasion and illegitimate manipulation of

thoughts, but influence campaigns may well breach this right.

3.1.2 The right to privacy

Article 17 of ICCPR states:

‘1. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or

correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.

47

UN Human Rights Council Resolutions (2012-2018), The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet,

UN Doc A/HRC/RES/38/7 (5 July 2018), A/HRC/RES/32/13 (1 July 2016), A/HRC/RES/26/13 (26 June 2014), A/HRC/RES/20/8 (5 July

2012).

48

Kate Jones (2019) disaggregates the impact of online disinformation on human rights in the political context. She identifies

concerns with respect to five key rights: right to freedom of thought and the right to hold opinions without interference; the right

to privacy; the right to freedom of expression; the right to participate in public affairs and vote in elections.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

11

2. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.’

Article 12 of UDHR stipulates that: ‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy,

family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation.’

The use of disinformation can interfere with privacy rights in two ways: by damaging the individual

reputation and privacy of the person it concerns in certain circumstances, and by failing to respect the

privacy of individuals in its target audience. The Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy states that

‘privacy infringements happen in multiple, interrelated and recurring forms facilitated by digital

technologies, in both private and public settings across physical and national boundaries’

49

. Online privacy

infringements extend offline privacy infringements. Digital technologies amplify their scope and intensify

their impact.

The right to privacy in the digital age is exposed to a new level of vulnerabilities, ranging from personal

attacks through social media to the harvesting and use of personal data online for micro-targeting

messages. However, as the case Tamiz v the United Kingdom showed

50

there is a thin line between freedom

of expression and the right to privacy. In that particular case, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)

reinforced the protection of freedom of expression by confirming a UK Court decision to reject the libel

claim of a British politician against Google Inc. because it hosted a blog which published insulting

comments against him.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has affirmed that there is ‘a growing global

consensus on minimum standards that should govern the processing of personal data by States, business

enterprises and other private actors’

51

. These minimum standards should guarantee that the ‘processing

of personal data should be fair, lawful and transparent in order to protect citizens from being targeted by

disinformation that can for instance cause harm to individual reputations and privacy’, even to the point

of inciting ‘violence, discrimination or hostility against identifiable groups in society’. In this context, the

EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is founded on the right to protection of personal data in EU

law. The GDPR imposes controls on the processing of personal data, requiring that data be processed

lawfully, fairly and transparently.

3.1.3 The right to freedom of expression

The UDHR and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), in Article 19, protect the

right to freedom of expression (see full quotation above, under Section 3.1.1).

The right to disseminate and access information is not limited to true information. In March 2017, a joint

declaration by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the Organization for

Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Representative on Freedom of the Media, the Organization of

American States (OAS) Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and the African Commission on

Human and Peoples all stressed that ‘the human right to impart information and ideas is not limited to

‘correct’ statements, that the right also protects information and ideas that may shock, offend and disturb’

52

. They declared themselves alarmed both ‘at instances in which public authorities denigrate, intimidate

and threaten the media’, as well as others stating that the media is ‘the opposition' or is ‘lying’ and has a

hidden political agenda’. They further warned that ‘general prohibitions on the dissemination of

49

OHCHR, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy for the 43th session of the Human Rights Council, February

2020.

50

Tamiz v the United Kingdom (Application no. 3877/14) [2017] ECHR (12 October 2017), seen in European Court of Human Rights

upholds the right to freedom of expression on the Internet, Human Rights Law Centre, 2017 [Accessed on 28/02/21]

51

OHCHR, The right to privacy in the digital age, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights for the 39

th

session of the Human Rights Council, August 2018.

52

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Joint declaration on freedom of expression and ‘fake news’,

disinformation and propaganda, March 2017.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

12

information based on vague and ambiguous ideas, including ‘false news’ or ‘non-objective information’,

are incompatible with international standards for restrictions on freedom of expression [...] and should be

abolished’.

In April 2020, the same signatories were parties to a new ‘Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and

Elections in the Digital Age’, in which they expressed ‘grave concern’ about the threats and violent attacks

that journalists may face during elections, adding that targeted smear campaigns against journalists,

especially female journalists, undermine their work as well as public trust and confidence in journalism.

The agreed text not only calls for protecting freedom of expression, but also points at political authorities

passing laws limiting rights, restricting Internet freedom or ‘abusing their positions to bias media coverage,

whether on the part of publicly-owned or private media, or to disseminate propaganda

53

that may

influence election outcomes’. The signatories put forward a reminder that the states’ obligation to respect

and protect freedom of expression is especially pronounced in relation to female journalists and

individuals belonging to marginalised groups

54

.

3.1.4 Economic, social and cultural rights

Disinformation impacts not only the political sphere, but also economic, social and cultural aspects of life,

from personal mindsets about vaccinations to disavowing cultures or different opinions. Disinformation

feeds polarisation and erodes trust both within institutions and amongst communities. Such manipulation

tactics can damage personal rights to health and education, participation in cultural life and membership

of a community.

There are several economic, social and cultural rights that can be disrupted by disinformation, such as

those included in Article 25(1) UDHR: ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health

and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and

necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability,

widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control’.

Article 12 of the ICESCR affirms:

‘1. The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the

highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.’

The most prominent recent example relates to disinformation around COVID-19, which has distorted

freedom of choice even within a health context (see also Chapter 4 on COVID-19). Blackbird

55

, an

organisation whose purpose it is to enhance decision making and empower the pursuit of information

integrity’

56

, released studies analysing the volume of disinformation generated on Twitter as a result of the

COVID-19 outbreak. In one of its reports

57

, Blackbird identified one of the disinformation campaigns

unfolding in Twitter as ‘Dem Panic’, which had the goal of de-legitimising the Democratic Party in the US

for their early warnings about the coronavirus and the need to introduce preventative measures.

Downplaying effects of the virus can clearly have negative impacts on public health. The Lancet warned in

October 2020 that the anti-vaccine movement together with digital platforms are becoming wealthier by

hosting and spreading disinformation campaigns in social media

58

. It is claimed that ‘anti-vaxxers have

53

In Article 20(1) of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the term propaganda ‘refers to the

conscious effort to mould the minds of men [sic] so as to produce a given effect’ (Whitton, 1949; via Jones, 2019).

54

OSCE, Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and Elections in the Digital Age, April 2020.

55

Blackbird AI, Disinformation reports, 2020.

56

The founders of this organisation ‘believe that disinformation is one of the greatest global threats of our time impacting national

security, enterprise businesses and the general public’. Accordingly, their ‘mission is to expose those that seek to manipulate and

divide’.

57

Blackbird AI, COVID-19 Disinformation Report – Vol. 2, March 2020.

58

Center for Countering Digital Hate, The Anti-vaxx industry. How Big-Tech powers and profits from vaccine misinformation’ in T.

Burki, The online anti-vaccine movement in the age of COVID-19, The Lancet, Vol. 2, October 2020.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

13

increased their following by at least 7·8 million people since 2019’ and hence ‘the anti-vaccine movement

could realise USD 1 billion in annual revenues for social media firms’.

3.2 Impact on democratic processes

3.2.1 Weakening of trust in democratic institutions and society

Disinformation has an impact on the basic health and credibility of democratic processes. This has become

the core of recent positions taken by international organisations, such as Resolution 2326 (2020) of the

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) expressing concern ‘about the scale of

information pollution in a digitally connected and increasingly polarised world, the spread of

disinformation campaigns aimed at shaping public opinion, trends of foreign electoral interference and

manipulation’

59

. Information and shared narratives are a precondition for good quality democratic public

discourse.

In this context, the European Parliament views disinformation as an ‘increasing systematic pressure’ on

European societies and their electoral stability

60

. The European Commission’s strategy Shaping Europe’s

Digital Future

61

considers that ‘disinformation erodes trust in institutions along with digital and traditional

media and harms our democracies by hampering the ability of citizens to take informed decisions’. It also

warns that disinformation is set to polarise democratic societies by creating or deepening tensions and

undermining democratic pillars such as electoral systems.

There are a number of ways in which disinformation weakens democratic institutions. These include the

use of social media to channel disinformation in coordinated ways so as to undermine institutions’

credibility. As trust in mainstream media has plummeted

62

, alternative news ecosystems have flourished.

Online platforms’ business model pushes content that generates clicks and this has increased polarisation.

This favours the creation of more homogeneous audiences, undercuts tolerance for alternative views

63

.

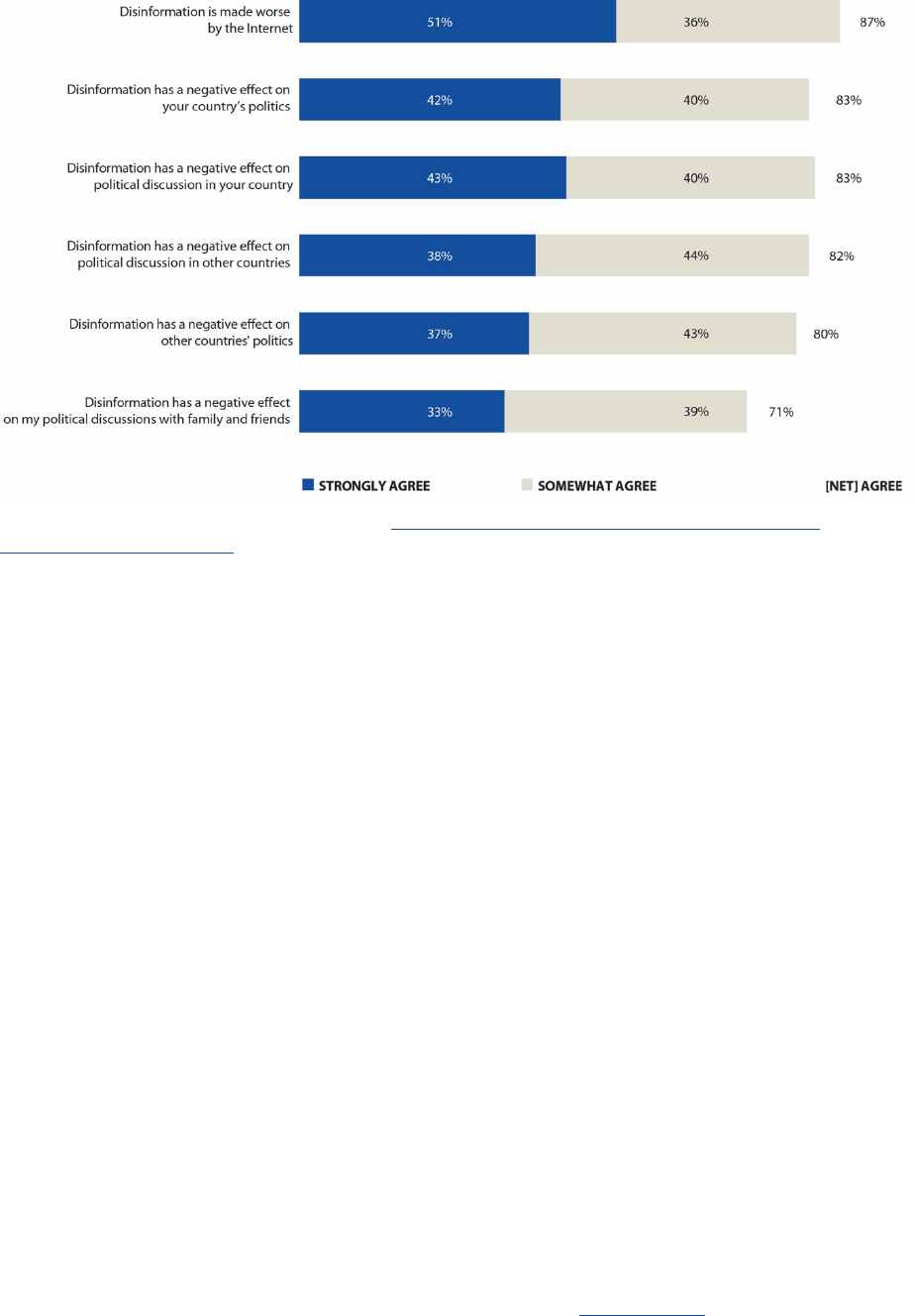

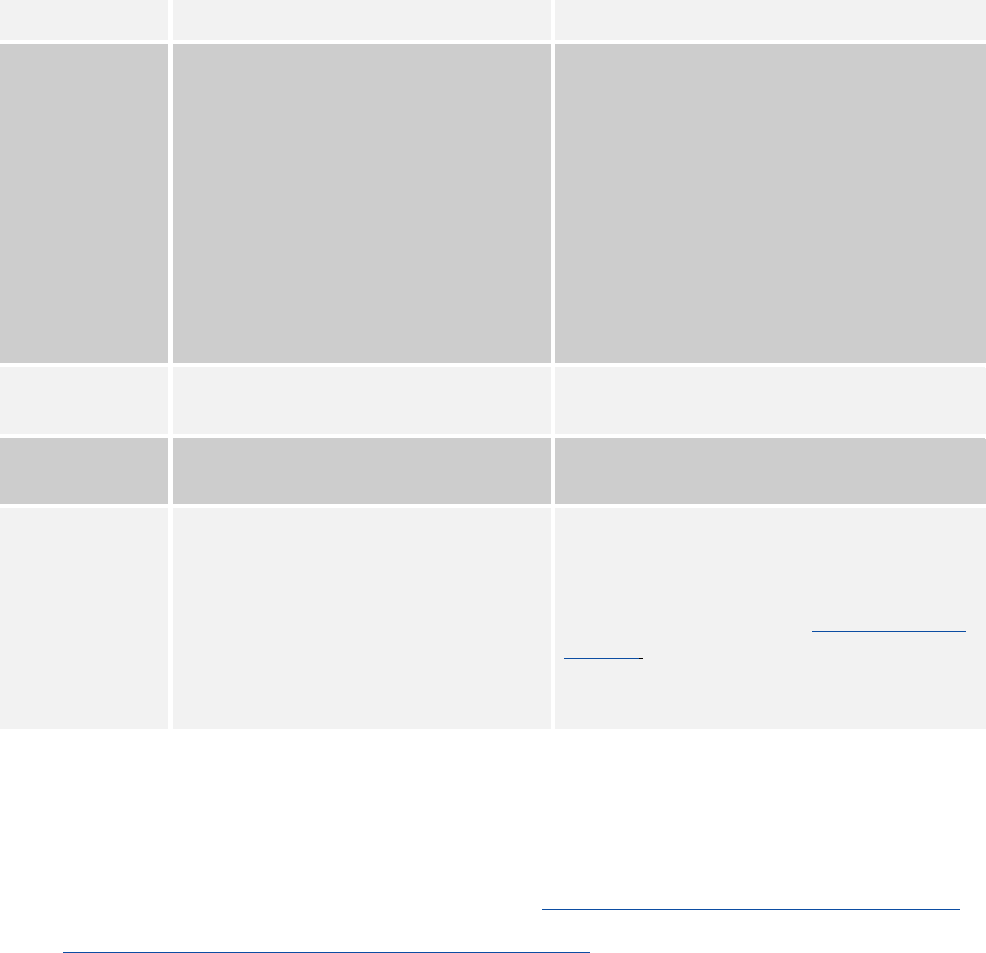

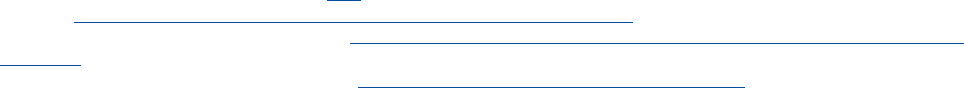

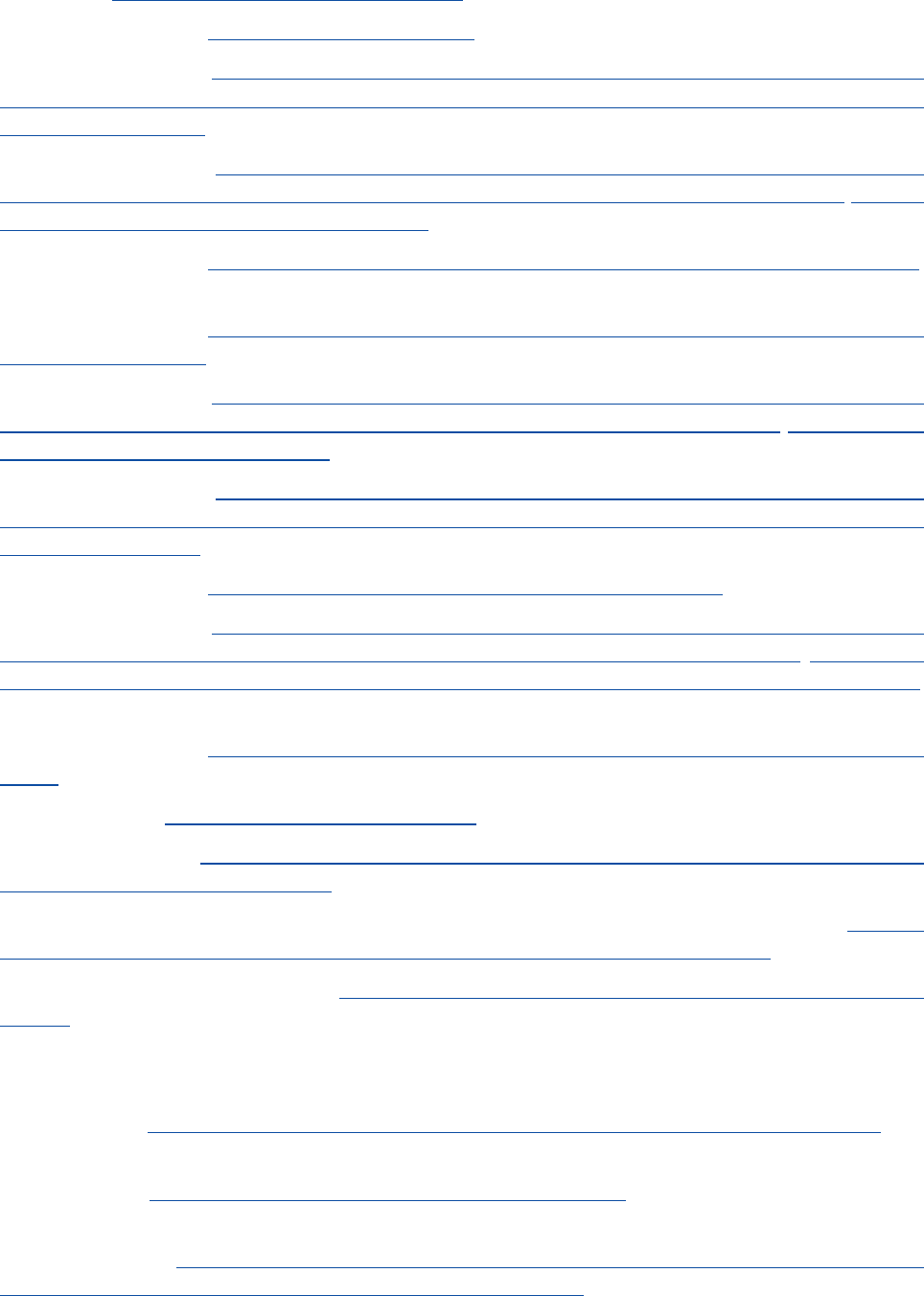

Figure 2 below suggests that around 80 % of people believe that disinformation has negative impacts in

their own countries’ politics, in other countries’ politics and in political discussions among families and

friends, which increases polarisation.

Surveys also show that disinformation can sow distrust in different pillars of democratic institutions,

including public institutions such as governments, parliaments and courts or their processes, public

figures, as well as journalists and free media

64

. For example, a survey undertaken by Ipsos Public Affairs and

Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) reports that, due to the spread of disinformation,

many citizens have less trust in media (40 %) and government (22 %)

65

.

59

PACE, Democracy Hacked? How to Respond?, Resolution 2326 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe on 31

January 2020 (9

th

Sitting), January 2020.

60

European Parliament, European Parliament resolution of 23 November 2016 on EU strategic communication to counteract

propaganda against it by third parties, P8_TA(2016)0441, November 2016.

61

European Commission, Tackling online disinformation, webpage. [Accessed on 15 October 2020]

62

Nic Newman, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andi and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2020.

63

Massimo Flore, Understanding Citizen’s Vulnerabilities: form Disinformation to Hostile Narratives, JRC Technical Report, European

Commission, 2020.

64

IPSOS Public Affairs and Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Internet security and trust, CIGI IPSOS Global

Survey 2019, Vol 3, 2019.

65

IPSOS and CIGI, 2019, p 138.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

14

Figure 2. The Political Impacts of Disinformation

66

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on CIGI-Ipsos, 2019 CIGI-Ipsos Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust., 2019; CIGI-IPSOS,

Internet security and Trust. Part 3, 2019.

3.2.2 The right to participate in public affairs and election interference

Article 21 of the UDHR states:

‘1. Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen

representatives’;

3. The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in

periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret

vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.’

Article 25 of the ICCPR defends that:

‘Every citizen shall have the right and opportunity, without any of the distinctions mentioned in Article 2

and without unreasonable restrictions:

• To take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives;

• To vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage

and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors;

• To have access, on general terms of equality, to public service in his country.’

According to the UN Human Rights Committee, states are obliged to ensure that ‘Voters should be able to

form opinions independently, free of violence or threat of violence, compulsion, inducement or

66

The percentage refers to people interviewed in 25 different countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany,

Great Britain, Hong Kong (China), India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, South Africa,

Republic of Korea, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey and the United States) accounting for 1.000+ individuals in each

country during December 2018 and February 2019. See the original source (IPSOS-CIGI, 2019) for more information about the

methodology.

The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world

15

manipulative interference of any kind’

67

. Election interference can be defined as unjustified and illegitimate

ways of influencing people’s minds and voters’choices, thereby reducing citizens’ abilities to exercise their

political rights

68

. This means that the right to vote has to be exercised without interference with freedoms

of thought and opinion, with the right to privacy and without hate speech. Many governments’ use of

disinformation contradicts this injunction. Even where they are not directly using disinformation in

electoral campaigns, other states may be falling short in protecting this right on behalf of their citizens.

Foreign states and non-state actors are also able to influence and undermine elections through digital

disinformation

69

. Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) purchased around 3 400 advertisements on

Facebook and Instagram during the US 2016 election campaign and, according to a 2019 Report ‘Russian-

linked accounts reached 126 million people on Facebook, at least 20 million users on Instagram, 1.4 million

users on Twitter, and uploaded over 1.000 videos to YouTube’

70

.

Whether or not successful, manipulating elections by affecting voters’ opinions and choices through

disinformation damages democracy and creates a trail of doubt as to whether democratic institutions

actually work well in reflecting citizens’ choices.

3.3 Digital violence and repression

Article 20(2) of the ICCPR states that:

‘2. Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination,

hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.’

Disinformation is associated with a rise in more dramatic and grave digital violence. Digital violence has

been defined as using mobile phones, computers, video cameras and similar electronic devices with

intention to frighten, insult, humiliate or hurt a person in some other way

71

. The term ‘cyber-violence’,

includes a range of controlling and coercive behaviours, such as cyber-stalking, harassment on social

media sites, or the dissemination of intimate images without consent. Here, the instigators of digital

violence can be state and non-state actors as well as private groups or individuals.

In this context, digital repression means the coercive use of information and communication technologies

by a state to exert control over not only potential, but also existing challenges and challengers. Digital

repression includes an assortment of tactics through which states can use digital technologies to monitor

and restrict the actions of its citizens, including digital surveillance, advanced biometric monitoring,

disinformation campaigns and state-based hacking

72

. These actions self-evidently infringe core democratic

rights like the right to privacy and to freedom of expression.

In multiple political systems, cyber militias and ‘troll farms’ are used to drown out dissenting voices,

accusing them of spreading ‘fake news’ or being ‘enemies of the people’, a sort of censorship through

noise

73

. Experts warn against the practice of ‘state-sponsored trolling’, which consists of governments

67

UN Committee on Human Rights, General Comment 25, ‘The Right to Participate in Public Affairs, Voting Rights and the Right to

Equal Access to Public Service’, 1510

th

meeting (fifty-seventh session), 12 July 1996.

68

UNHR, ‘Monitoring Human Rights in the Context of Elections’, in Manual on Human Rights Monitoring, chapter 23, 2011.

69

Suzanne Spaulding, Devi Nair, and Arthur Nelson, Beyond the Ballot: How the Kremlin Works to Undermine the U.S. Justice

System, Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2019.

70

Robert Mueller, Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, U.S. Department of Justice,

March 2019.

71

Dragan Popadic Dragan and Dobrinka Kuzmanovic, Utilisation of Digital Technologies, Risks, and Incidence of Digital Violence

among students in Serbia. Unicef Report, 2013.

72

Steven Feldstein, How Artificial Intelligence Is Reshaping Repression, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 30, 2019, pp 40-52.

73

Peter Pomerantsev, ‘Human rights in the age of disinformation’, Unherd, published on 8 July 2020. [Accessed on 15 August 2020]

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

16

creating online content to attack opposition and discredit critical voices of dissent, thereby cutting across

basic standards of democratic debate which should be open and pluralistic.

While this study’s remit is limited to legal content, current disinformation challenges cannot be divorced

from the concept of ‘hate speech’, commonly referring to any communication that disparages a person or

a group on the basis of some characteristic such as race, colour, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation,

nationality, religion, or other characteristic. Disinformation can be an important part of this. Incitement to

hatred and discrimination (without advocacy of violence) is illegal in many EU Member States, unlike in the

United States. To address this challenge, in May 2016 the European Commission agreed with Facebook,

Microsoft, Twitter and YouTube, on a Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online

74

.

Coordinated online hate speech against racial and ethnic minorities has led to violence in different places

and disinformation has been used to attack minorities and human rights defenders around the world

75

.

For

instance: in Sri Lanka and Malaysia targeted disinformation resulted in an outburst of violence against

Muslims; in Myanmar, the military used Facebook to incite violence against the Rohingya; and rumours

about Muslims in India circulating on WhatsApp have resulted in lynchings

76

.

3.4 Counter-disinformation risks

Disrupting human rights and democracy by disinformation is clearly of serious concern. However, there is

another side to the democratic equation, namely that action against disinformation also carries risks.

Tackling disinformation through a human rights prism involves difficult trade-offs and delicate policy

balances. Disinformation itself threatens to produce core breaches in human rights. Hence, countering

disinformation is an important contribution in efforts to safeguard global human rights. Yet, countering

disinformation can also itself constrict human rights. Even if disinformation can easily damage human

rights, both within the EU and at international level, the legal and political abuse of what has been labelled

the ‘fight against fake news’ has in some countries also resulted in reduced freedom of expression and

political dissent. This is becoming a more serious problem both inside and outside the European Union

77

.

Consequently, in defending measures to tackle disinformation, the European Union must be careful to

tackle both human rights impacts resulting from disinformation and any rights abuses inadvertently

caused by attempts to counter disinformation in such a way that does not encourage third-country

governments’ human rights breaches. Erosion of rights can be caused, for instance, by: government

interferences with internet services; state censorship or restrictions to online speech; and obstacles to the

proper functioning of media outlets. Any actions – be they legal, administrative, extra-legal or political –