Dušan Mramor,

Slovenia and the EU: successes and challenges

I still remember vividly the envious comments of my US colleague with whom I have studied

and worked at the IU School of Business, Bloomington, Indiana before Slovenia became a

widely recognized new country. He pointed out that, while he was “confined to ivory tower

academic work”, I had the privilege of being deeply involved in “building a new country”.

When enormous political, economic and institutional changes started in Slovenia at the end of

the 80s, I was lucky that my knowledge was in the field of (market economy) finance. This

was more of a rarity than a common feature in small Slovenia at the time. Hence, I was asked

to assist in developing the financial system and institutions needed for the new country, as

well as in transitioning from the Yugoslav economic system of self-management with limited

need of finance to market economy where finance is playing one of the major roles.

Professionally and academically these were exceptionally exciting times for me that came

with enormous responsibility and exhausting work.

As it was, “the transition to market economy with democratic political system” began way

before Slovenia formally entered the EU in May 2004, some 15 years earlier. It all started

with a military conflict that followed the declaration of Slovenia’s independence. A new

country could only start functioning with proper institution and capacity building and by

getting a worldwide recognition. The positive spirit, the satisfaction and joy to achieve the

dream of our own independent country, extremely motivated and professional leaders all

contributed to the success of this formidable task.

In my opinion, the main driving forces for reforms were the goals ahead of us: of becoming a

member of the EU, adopting Euro as a new currency, entering the Schengen zone, becoming

a member of the OECD, … all the elements of joining the club of developed countries with a

bright future. In Slovenia, the support for these integrations was amongst the highest in the

EU. Even before the formal negotiations have started, the perspective of integration alone

was driving the necessary changes.

The fear of failing to complete the formal integration in the first wave forced the leaders of

the country to put the most skilled and experienced individuals to top positions. They not

only led very prudent and growth enhancing economic policy (monetary as well as fiscal) but

also negotiated better terms in integration agreements (i.e. EU Association Agreement) than a

number of other transition countries.

In spite of high professionalism, the transition and integration tasks were extremely

demanding as there were no established good practices and the structure of the economy was

very specific. Opinions on the best course of action differed greatly between the European

Commission, the international (financial) organizations, and the Slovenian economists. The

views expressed were sometimes coming from opposing angles, many times reflecting vested

interests behind the proposals. The most heated disagreements were on how to privatize and

on whether to adopt a fixed or flexible exchange rate policy. I was heavily involved in these

discussions, not only through my academic work and its dissemination through articles and

interviews but also through consultancy to the government as coordinator of many projects

(i.e. strategy for the development of financial system, privatization of certain industries,) as a

member of strategic councils, and in delivering the agreed changes through a number of

positions I was appointed to (i.e. member of the national bank council, chairman of the

Slovenian SEC, minister of finance).

First 15 years of transition (from 1989 to 2004)

This period was analyzed at its end in a paper entitled: “Soft Landing” in the ERM2: Lessons

from Slovenia.

1

Written together with Velimir Bole, my economic adviser during my first

term as finance minister. We presented the logic of the economic decision-making used in

the process of joining the EU and EMU for Slovenia that in our opinion proved successful.

Our main observations were the following:

At the beginning of the 1990's there was a wide discussion among academics and politicians

on the sequencing priorities the countries in transition should follow – first, structural

changes and then macroeconomic stability, or vice versa; gradualist or »big-bang« approach.

Generally, the European transition countries also set the goal of joining the EU, and

ultimately, the EMU. Nominal and real convergence was necessary to successfully join the

EU and EMU. They required very complex (and difficult) economic decisions. This caused

not only additional requirements for structural changes, but also new exogenous shocks and

additional constraints in their economic policies.

In this period Slovenia undertook its transition in three phases. Gradualism was the main

characteristic of the three, while the priority of macroeconomic stabilization was followed in

the first phase until 1995 and structural adjustments in the second phase until 2000. Slovenia

needed an additional phase, called the »landing phase« that ended by entering EU in May

2004 and ERM2 less than two months later.

In the period after 1995, structural adjustments were needed to mitigate market distortions.

Distortions in the market structure, especially in the non-tradable (versus tradable) sector,

distortions (segmentation and lack of flexibility) on the labor market, unsustainable pension

system and shallowness of the financial intermediation were among the most important areas

of the change.

By 1999 Slovenia achieved a considerable level of macroeconomic stability with quite stable

economic growth and low unemployment. At the same time, market structure distortions and

a slowly but stubbornly deteriorating fiscal stance were the main macroeconomic drawbacks.

Additionally, EU accession commitments and fixed horizon of convergence policy triggered

changes in the macroeconomic environment. Capital controls had to be removed, VAT and

excises introduced, and several regulated prices adjusted and economic policy constraints

increased. Policy goals were changed as well, as short-term nominal convergence to

Maastricht criteria came into policy focus. However, to prevent potential high

macroeconomic costs (in terms of real convergence) of such enforced nominal convergence,

structural as well as macroeconomic policy changes were necessary. Fiscal pressures and

1

BOLE, V. and MRAMOR, D., Soft landing in the ERM2 - Lessons from Slovenia. In PRASNIKAR, J.(ed.):

Competitiveness, Social Responsibility and Economic Growth. Nova Science Publishers, 2006, pp. 103 – 123.

market structure differences between tradable and non-tradable sector were the main

constraints of policy makers in the landing phase.

In the landing phase, during my first term as finance minister, we used two strategic

principles of economic policy: the basic principle of not allowing equilibrium in one segment

to be achieved by causing or allowing disequilibrium in other main macroeconomic

segments, and that of high coordination of the monetary and fiscal policy.

The monetary policy focused on controlling domestic demand to curb prices of non-tradables.

To be instrumentally consistent, monetary policy used the flexible exchange rate policy for

keeping the interest rate differences between the Slovenian currency, tolar, and foreign

exchange denominated financial claims equal to the foreign currency risk premium.

The fiscal policy was active in achieving fiscal convergence criteria and, in coordination with

the monetary policy, also in supporting convergence of nominal long-term interest rates and

inflation. It activated a series of measures by which de-indexation, lowering of inflation

expectations, mitigation of supply side price shocks (triggered by regulated prices and tax

policy), government debt restructuring, stricter control, and restructuring of government

spending, were implemented.

A well-designed interplay of both policies was essential for mitigating long and short-term

threats of slower real convergence because of enforced nominal convergence. Achieving the

Maastricht criteria went hand in hand with relatively high economic growth, low

unemployment and external equilibrium.

Positive climate in the society with demanding accession commitments on one side, and

sound, quite unique economic policy with deep structural changes on the other side, lead to a

fast nominal and real conversion process. GDP per capita in PPP as percentage of EU28

average increased by 10 percentage points, from 75% to 85%, in the period from 1995 to

2004 (4

th

best relative increase among transition countries with maintaining the highest GDP

per capita in PPP).

Second 15 years (from 2004 to 2019)

Unfortunately, this period will be recorded completely differently, since the same level of

GDP per capita in PPP as percentage of EU28 was achieved in 2017 (the latest data) as in

2004 (85%), and the Czech Republic overtook Slovenia with the highest GDP per capita in

PPP as percentage of EU28 among transition countries. This was primarily the consequence

of inadequate economic policies before the world financial crises, where the impact of joining

the EMU on flexibility of economic policy and a need of increased fiscal policy flexibility

was not understood. Also, ill designed methodology of estimating the potential output for the

purpose of EA fiscal coordination and led to enormous loss of GDP during the crisis. Further,

inability to react swiftly to the crisis after it occurred caused its deepening and prolonging to

almost six years.

Abandoning the stability paradigm in 2005 was the key decision that lead to a procyclical

economic policy with anti-pension reform, an increase of government spending for public

sector wages (+17% in two years), intensive highway program as well as tax cuts (full effect:

-2,5% GDP), a switch from domestic to foreign public debt, etc. in the overheated world

economic environment. EC‘s economic assessment of Slovenia on the basis of inadequate

methodology for estimating structural fiscal deficit did not give the needed warning to change

the policy. Hence, Slovenia entered the crisis unprepared with 164% increase of foreign debt

since 2004, huge structural fiscal deficit and substantial loss of competitiveness.

In such circumstances the new government in 2009 was unable to unblock political standstill

that followed the shock and thus insufficiently reacted to the crisis. Important measures (i.e.

recapitalization of banks) were prevented due to political disagreements within the

government, in the coalition, and between the institutions (i.e. Bank of Slovenia and Ministry

of Finance). Although necessary structural reforms (pension, labour market) were adopted in

the parliament they were subsequently blocked by (miss)use of referendum and

Constitutional Court‘s inconsistent rulings.

The procyclical austerity was the economic orientation of the next 2012 government, again

inadequately reacting to the crisis. Its measures and reactions to the crisis included reduced

public sector wages, reduced public sector employment by freezing new gross employment

and layoffs at the age of 65, frozen pensions, bold announcements of austerity measures that

caused the biggest reduction in consumer confidence and consumer spending in Slovenia

ever, and statements by the top officials declaring the need for „Troika“ that initiated the

extraordinary reduction of business and investor‘s confidence, sending interest margins to

record levels. However, the pension and the labour market structural reforms were adopted,

and State Sovereign Holding (SSH) and the bad bank were established as recommended by

the European Commission.

Due to an extremely tense political situation, the next government took over in 2013 for only

1,5 years. Heavily guided by the recommendations within the excessive deficit and

macroeconomic imbalances procedures and poor access to financial markets the government

successfully focused on the structural reforms to rebuild trust of financial markets and

competitiveness. Among them were: the necessary changes of the constitution, bank

recapitalization, making the bad bank operational, intensive corporate restructuring and

enabling the SSH to start operating and privatizing. Planned austerity measures were not fully

implemented thus being less procyclical while extensive drawing (positive net) of the

remaining EU funds increased highly needed domestic demand. All these measures enabled

the switch of economic growth from negative to positive. It is probably fair to conclude that

the recommendations of EU institutions and efforts of Slovenia to follow them closely when

in agreement, enabled increase of international competitiveness and exceptional growth of

exports even during crisis.

The next government served for almost full 4-year term (2014-2018). Serving as finance

minister for the second time in the first half of the term was an overwhelming intellectual

challenge. After a thorough economic analysis we opted for counter-cyclical economic policy

orientation of stability with growth. The concept was extensively debated with the EC and

differences of opinions helped us to avoid important mistakes. The structure of the orientation

was:

1. Fiscal stimulus:

• Intensive drawing of a large share (net 2,9% GDP) of the 2007-2013 financial

perspective of EU funds still at disposal

• Public expenditure growth lower than revenue growth but positive

• Mid-term fiscal objective in 2020 (not recommended 2017)

• 2015 – fiscal effort goal only nominal deficit of less than 3%

• 2016, 2017 – EU addressed inappropriate results of structural fiscal deficit

estimates and reduced requested fiscal effort for Slovenia

2. Domestic private demand - restoring business and consumer confidence with political

stability, non-aggressive agreement type decision making, social agreement reached for

2015/16, cover wage agreements with labour unions before each Christmas, continuous

system changes for the improvements of business environment, etc.

3. Improving efficiency of public investments with channeling public funds into projects

with higher GDP multiplier and wit improvement of control.

4. Structural changes concerning:

• Fiscal sustainability

• Improvement of business environment:

• Restoring financing:

1. Bank recapitalization and restructuring

2. Restructuring of troubled firms (also through privatization)

• Reducing administrative burden

1. Simplifying construction and environmental permits

2. Simplifying tax procedures

• Improving competitiveness:

1. Improving efficiency of state owned firms

2. Improvements in the legal system

3. Tax shifting

The economic results were outstanding, nevertheless, they required enormous effort as public

distrust and negative attitude towards politics after a long hardship during the severe crisis

was making policy decisions and delivery very hard work.

The next 15 years

The crisis revealed very painfully that EMU (EU) is not designed well for the downturn. For

Slovenia and many peripheral EU countries, the costs of misdiagnosis of the situation after

2005 were enormous. To put it mildly, the consequences of the very strange signals of the key

European fiscal framework indicators (the potential output, output gap and structural deficit),

prepared by the Commission in 2016, could have also been very painful. However, only

detecting and avoiding the wrong estimates of the potential output concepts for Slovenia

prepared by the European fiscal framework is not enough. National macroeconomic stability,

especially in small economies, needs a new logic and implementation of the European

stabilization framework.

Especially EA’s peripheral countries were struggling to overcome serious challenges of the

crisis, with core countries in most cases designing the solutions. Lessons learned are reflected

in current very intense debates on how to deepen the EA and opinions are very diverse. Let

me point out one topic that is not only very relevant to non-core, former countries in

transition, but also to the EA (EU) as a whole.

The usual starting point in discussions of EA deepening is that the changes should prevent

irresponsible behaviour of peripheral countries that affects the whole EA. However, there is

ample evidence that EMU is not weak (shallow) primarily because of irresponsible behaviour

of the so called „Periphery “.

First, the EMU‘s monetary policy is designed for the needs of the Core and is ill suited for

the Periphery - in many cases not active enough. Second, the fiscal rules disable efficient

fiscal policy, especially during crisis, and the current fiscal rules are highly procyclical thus

detrimental especially for the Periphery. Namely, partly based on my experiences since most

research does not study shocks in the Periphery but predominantly in the Core, the Periphery

is much more prone to asymmetric shocks than the Core due to a different structure of the

economy. Solving the problem of asymmetry with structural reforms that lead to full

convergence is an illusion. For example, Slovenia can never reach Germany ‘s structure of

economy for numerous reasons (size, infrastructure, geographies, specialization, labour force

...). Also, shocks in the Periphery are amplified by serving as a shock absorber (i.e. Vienna

agreement, real estate investments in Spain, …) for the Core.

Economic difficulties in one peripheral country immediately cause contagion in other

Peripheries, and major ones spread also to the Core. As can be clearly seen from the

following table, when Slovenia had all economic policy instruments available, mostly before

June 2004 when it entered EU and ERM2 and EU fiscal rules and ECB monetary policy

prevailed, its economic policy was much more prudent than that of the core or the whole EA.

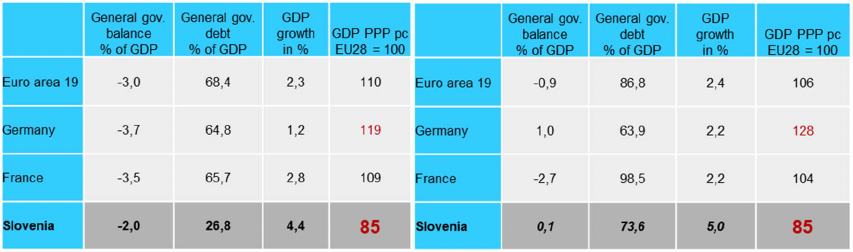

2004 2017

Source: Eurostat

Thus, the actual problem is that the Periphery is lacking essential economic policy

instruments to respond to and neutralize shocks. The solutions should be searched in enabling

EMU members to respond pre-emptively or at least immediately with efficient economic

policy instruments. The system should be mainly decentralized with the tools available to the

members of the EMU for pre-emptive actions to avoid asymmetric shocks. The centralized

part should enact a quick (rather automatic) response and not a slow process of

conditionality. Also, sometimes the process of conditionality results in a forced privatization

of state assets at low prices bought by the Core. Such outcomes are risky also for EU

existence.

Instead of a conclusion

I am very proud that Slovenia became a EU country among the first group of transition

economies and benefited enormously in the first 15 years during the accession. And even

with the disappointments of the second 15 years, due to our own mistakes and the impact of

some inadequate EU arrangements, the pride is still there. And as to the envy of my

academic colleagues - no need. There are more than enough intellectual challenges left to

enable EU using its full potential for economic prosperity in a peaceful, sustainable and

harmonious EU society.