BUSINESS ANALYSIS

&VALUATION

USING FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

BUSINESS ANALYSIS

&VALUATION

USING FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

5e

KRISHNA G. PALEPU, PhD

Ross Graham Walker Professor of Business Administration

Harvard University

PAUL M. HEALY, PhD, ACA

James R. Williston Professor of Business Administration

Harvard University

Australia • Brazil • Japan • Korea • Mexico • Singapore • Spain • United Kingdom • United States

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

This is an electronic version of the print textbook. Due to electronic rights restrictions,

some third party content may be suppressed. Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed

content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. The publisher reserves the right

to remove content from this title at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. For

valuable information on pricing, previous editions, changes to current editions, and alternate

formats, please visit www.cengage.com/highered to search by ISBN#, author, title, or keyword for

materials in your areas of interest.

Business Analysis & Valuation: Using

Financial Statements, 5th edition

Krishna G. Palepu and Paul M. Healy

Senior Vice President, LRS/Acquisitions &

Solutions Planning: Jack W. Calhoun

Editor-in-Chief: Rob Dewey

Senior Acquisitions Editor: Matt Filimonov

Senior Developmental Editor: Craig Avery

Editorial Assistant: A. J. Smiley

Senior Market Development Manager:

Natalie Livingston

Senior Brand Manager: Kristen Hurd

Marketing Manager: Heather Mooney

Marketing Communications Manager:

Sarah Greber

Marketing Coordinator: Eileen Corcoran

Senior Art Director: Stacy Shirley

Production Management, Internal Design,

and Composition: PreMediaGlobal

Media Editor: Bryan England

Rights Acquisition Director: Audrey

Pettengill

Rights Acquisition Specialist, Text and

Image: Audrey Pettengill

Senior Manufacturing Planner: Doug Wilke

Cover Designer: Red Hangar Design

Cover Image(s): ©iStock Photo/

franckreporter

© 2013, 2008 South-Western, Cengage Learning.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright

herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by

any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited

to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, web distribution,

information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems,

except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States

Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at

Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all

requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions.

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012948788

Student Edition ISBN 13: 978-1-111-97230-1

Student Edition ISBN 10: 1-111-97230-3

Student Edition with CD ISBN 13: 978-1-285-42618-1

Student Edition with CD ISBN 10: 1-285-42618-5

South-Western

5191 Natorp Boulevard

Mason, OH 45040

USA

Cengage Learning is a leading provider of customized learning solu-

tions with office locations around the globe, including Singapore, the

United Kingdom, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, and Japan. Locate your local

office at: www.cengage.com/global

Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by

Nelson Education, Ltd.

For your course and learning solutions, visit www.cengage.com

Purchase any of our products at your local college store or at our

preferred online store www.cengagebrain.com.

Printed in the United States of America

12345671615141312

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

PREFACE

F

inancial statements are the basis for a wide range of business analysis. Managers

use them to monitor and judge their firms’ performance relative to competitors,

to communicate with external investors, to help judge what financial policies they

should pursue, and to evaluate potential new businesses to acquire as part of their invest-

ment strategy. Securities analysts use financial statements to rate and value companies

they recommend to clients. Bankers use them in deciding whether to extend a loan to a

client and to determine the terms of the loan. Investment bankers use them as a basis for

valuing and analyzing prospective buyouts, mergers, and acquisitions. And consultants

use them as a basis for competitive analysis for their clients.

Not surprisingly, therefore, we find that there is a strong demand among business stu-

dents for a course that provides a framework for using financial statement data in a vari-

ety of business analysis and valuation contexts. The purpose of this book is to provide

such a framework for business students and practitioners. The first four editions of this

book have succeeded far beyond our expectations in equipping readers with this useful

framework, and the book has gained proponents in accounting and finance departments

in business schools in the United States and around the world.

CHANGES FROM THE FOURTH EDITION

In response to suggestions and comments from colleagues, students, and reviewers, we

have incorporated the following changes in the fifth edition:

• Data, analyses, and issues have been thoroughly updated.

• Where appropriate, lessons have been drawn from current events such as the

global financial crisis of 2008 and the ongoing European debt crisis.

• The financial analysis and valuation chapters (Chapters 6–8) have been updated

with a focus on firms in the U.S. retail department store sector, primarily TJX and

Nordstrom. In addition, we have provided a more cohesive overall discussion of

the four key components of effective financial statement analysis that this book

examines by introducing these companies in our discussion of strategy analysis

in Chapter 2 and staying with them through the accounting, financial, and

prospective analyses that follow.

• We have provided a greatly expanded examination of the impact of accounting

adjustments (introduced in Chapter 4) on company analysis by analyzing both

unadjusted and adjusted financial ratio and cash flow measures for TJX and

Nordstrom in Chapter 5, and by then using adjusted numbers for TJX in the

prospective analysis of Chapters 6–8.

• The topic of U.S. GAAP/IFRS convergence is introduced and examined, with

discussion and examples in comparing companies reporting under U.S. GAAP and

IFRS, and a brief discussion on important remaining differences between U.S.

GAAP and IFRS.

• An expanded discussion of fair value accounting is included, given its increasing

use globally and also its much discussed role in the 2008 financial crisis.

• We have streamlined and greatly enhanced the readability of the discussion on the

theory behind valuation techniques in Chapters 7 and 8.

• In our Text and Cases edition, we have included new and updated Harvard

Business School cases. In all, we include 27 cases in this edition.

v

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

• We are introducing with this edition an online version of the BAV modeling tool,

which represents a significant enhancement of the tool over the previous

spreadsheet-based version. This comprehensive modeling tool implements the

analytical framework and techniques discussed in this book, and allows students to

easily import the financial statements of a company into the model from three

major data providers—Thomson ONE, Capital IQ, and the Compustat database of

the Wharton Research Data Services—as well as to import manually created state-

ments. A user-friendly interface allows the analyst to navigate through the tool

with ease. The tool facilitates the following activities: (1) recasting the reported

financial statements in a standard format for analysis; (2) performing accounting

analysis as discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, making desired accounting adjustments,

and producing restated financials; (3) computing ratios and free cash flows as

presented in Chapter 5; (4) producing forecasted income, balance sheet, and cash

flow statements for as many as 15 years into the future using the approach dis-

cussed in Chapter 6; (5) preparing a terminal value forecast using the abnormal

earnings, the abnormal returns, and discounted cash flow methods as discussed in

Chapters 7 and 8; and (6) valuing a company (either assets or equity) from these

forecasts as also discussed in Chapters 7 and 8. We have seen that the BAV

modeling tool can make it significantly easier for students to apply the framework

and techniques discussed in the book in a real-world context, and we feel that the

new online version, with its enhanced data import flexibility and improved overall

interface, further enhances the usability and usefulness of this tool.

KEY F EATURES

This book differs from other texts in business and financial analysis in a number of

important ways. We introduce and develop a four-part framework for business analysis

and valuation using financial statement data. We then show how this framework can be

applied to a variety of decision contexts.

Framework fo r Analysis

We begin the book with a discussion of the role of accounting information and

intermediaries in the economy, and how financial analysis can create value in well-

functioning markets (Chapter 1). We identify four key components, or steps, of effective

financial statement analysis:

• Business strategy analysis

• Accounting analysis

• Financial analysis

• Prospective analysis

The first step, business strategy analysis (Chapter 2), involves developing an under-

standing of the business and competitive strategy of the firm being analyzed. Incorporat-

ing business strategy into financial statement analysis is one of the distinctive features of

this book. Traditionally, this step has been ignored by other financial statement analysis

books. However, we believe that it is critical to begin financial statement analysis with a

company’s strategy because it provides an important foundation for the subsequent anal-

ysis. The strategy analysis section discusses contemporary tools for analyzing a com-

pany’s industry, its competitive position and sustainability within an industry, and the

company’s corporate strategy.

vi

Preface

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Accounting analysis (Chapters 3 and 4) involves examining how accounting rules

and conventions represent a firm’s business economics and strategy in its financial state-

ments, and, if necessary, developing adjusted accounting measures of performance. In

the accounting analysis section, we do not emphasize accounting rules. Instead we

develop general approaches to analyzing assets, liabilities, entities, revenues, and

expenses. We believe that such an approach enables students to effectively evaluate a

company’s accounting choices and accrual estimates, even if they have only a basic

knowledge of accounting rules and standards. The material is also designed to allow stu-

dents to make accounting adjustments rather than merely identify questionable account-

ing practices.

Financial analysis (Chapter 5) involves analyzing financial ratio and cash flow mea-

sures of the operating, financing, and investing performance of a company relative to

either key competitors or historical performance. Our distinctive approach focuses on

using financial analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of a company’s strategy and to

make sound financial forecasts.

Finally, in prospective analysis (Chapters 6–8) we show how to develop forecasted

financial statements and how to use these to make estimates of a firm’s value. Our dis-

cussion of valuation includes traditional discounted cash flow models as well as techni-

ques that link value directly to accounting numbers. In discussing accounting-based

valuation models, we integrate the latest academic research with traditional approaches

such as earnings and book value multiples that are widely used in practice.

Although we cover all four steps of business analysis and valuation in the book, we

recognize that the extent of their use depends on the user’s decision context. For exam-

ple, bankers are likely to use business strategy analysis, accounting analysis, financial

analysis, and the forecasting portion of prospective analysis. They are less likely to be

interested in formally valuing a prospective client.

Application of the Framework to Decision Contexts

The next section of the book shows how our business analysis and valuation framework

can be applied to a variety of decision contexts:

• Equity securities analysis (Chapter 9)

• Credit analysis and distress prediction (Chapter 10)

• Merger and acquisition analysis (Chapter 11)

• Communication and governance (Chapter 12)

For each of these topics we present an overview to provide a foundation for the class

discussions. Where possible we bring in relevant real-world scenarios and institutional

details, and also examine the results of academic research that are useful in applying

the analysis concepts developed earlier in the book. For example, the chapter on credit

analysis shows how banks and rating agencies use financial statement data to develop

analyses for lending decisions and to rate public debt issues. This chapter also presents

academic research on how to determine whether a company is financially distressed.

USING THE BOOK

We designed the book so that it is flexible for courses in financial statement analysis for

a variety of student audiences—MBA students, master’s in accounting students, executive

program participants, and undergraduates in accounting or finance. Depending upon the

audience, the instructor can vary the manner in which the conceptual materials in

the chapters and end-of-chapter questions are used. To get the most out of the book,

Preface vii

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

students should have completed basic courses in financial accounting, finance, and either

business strategy or business economics. The text provides a concise overview of some of

these topics. But it would probably be difficult for students with no prior knowledge in

these fields to use the chapters as stand-alone coverage of them.

If the book is used for students with prior working experience or for executives, the

instructor can use almost a pure case approach, adding relevant lecture sections as

needed. When teaching students with little work experience, a lecture class can be pre-

sented first, followed by an appropriate case or other assignment material. Alternatively,

lectures can be used as a follow-up to cases to more clearly lay out the conceptual issues

raised in the case discussions. This may be appropriate when the book is used in under-

graduate capstone courses. In such a context, cases can be used in course projects that

can be assigned to student teams.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first edition of this book was co-authored with our colleague and friend, Victor

Bernard. Vic was the Price Waterhouse Professor of Accounting and Director of the

Paton Accounting Center at the University of Michigan. He passed away unexpectedly on

November 14, 1995. While we no longer list Vic as a co-author, we wish to acknowledge

his enduring contributions to our own views on financial analysis and valuation, and to the

ideas reflected in this book.

We also wish to thank Scott Renner for his tireless research assistance in the revision

of the text chapters and in refining the online BAV model; Trenholm Ninestein of the

HBS Information Technology Group for his help in the development of the online

BAV model; Chris Allen and Kathleen Ryan of HBS Knowledge and Library Services

for assistance with data on financial ratios for U.S. companies; the Division of Research

at the Harvard Business School for assistance in developing materials for this book; and

our past and present MBA students for stimulating our thinking and challenging us to

continually improve our ideas and presentation.

We especially thank the following colleagues who gave us feedback as we wrote this

edition: Patricia Beckenholdt, University of Maryland University College; Timothy P.

Dimond, Northern Illinois University; Jocelyn Kauffunger, University of Pittsburgh;

Suneel Maheshwari, Marshall University; K. K. Raman, University of North Texas; Lori

Smith, University of Southern California; Vic Stanton, University of California, Berkeley;

Charles Wasley, University of Rochester.

We are also very grateful to Laurie Palepu and Deborah Marlino for their help

and assistance throughout this project. Special gratitude goes to Rob Dewey and Matt

Filimonov for their publishing leadership on this edition, to our colleagues, and to

Craig Avery and Heather Mooney at Cengage and Kalpana Venkatramani, project

manager at PreMediaGlobal, for their developmental, marketing, and production help.

We would like to thank our parents and families for their strong support and encourage-

ment throughout this project.

Krishna G. Palepu

Paul M. Healy

viii

Preface

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

AUTHORS

Krishna G. Palepu is the Ross Graham Walker Professor of Business Administration and

Senior Associate Dean for International Development at the Harvard Business School,

Harvard University. He also serves as Senior Adviser to the President for Global Strategy

at Harvard University. Prior to assuming his current leadership positions, Professor Palepu

held other positions at the School, including Senior Associate Dean, Director of Research,

and Unit Chair.

Professor Palepu’s current research and teaching activities focus on strategy and gover-

nance. In the area of strategy, his recent focus has been on the globalization of emerging

markets. He is a co-author of the book on this topic, Winning in Emerging Markets:

A Road Map for Strategy and Execution. He developed and taught a second year MBA

course, “Globalization of Emerging Markets,” which focuses on these issues. In addition,

Professor Palepu chairs the HBS executive education programs “Global CEOs Program

for China” and “Building Businesses in Emerging Markets.”

In the area of corporate governance, Professor Palepu’s work focuses on board engage-

ment with strategy. Professor Palepu teaches in several HBS executive education programs

aimed at members of corporate boards: “How to Make Corporate Boards More Effective,”

“Audit Committees in the New Era of Governance,”“Compensation Committees: New

Challenges, New Solutions.” Professor Palepu has served on a number of public company

and nonprofit Boards. He has also been on the Editorial Boards of leading academic jour-

nals, and has served as a consultant to a wide variety of businesses. In addition, he is a

researcher at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Professor Palepu has a doctorate in management from the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology and an honorary doctorate from the Helsinki School of Economics and Busi-

ness Administration.

Paul M. Healy is the James R. Williston Professor of Business Administration and Senior

Associate Dean, Director of Research at the Harvard Business School, Harvard University.

Professor Healy joined Harvard Business School as a Professor of Business Administration

in 1997. His primary teaching and research interests include corporate governance and

accountability, equity research at financial services firms, strategic financial analysis and

financial reporting. Professor Healy teaches in several executive education programs

and is faculty co-chair of Strategic Financial Analysis for Business Evaluation. Professor

Healy received his B.C.A. Honors (1st Class) in Accounting and Finance from Victoria

University, New Zealand, in 1977, his M.S. in Economics from the University of Rochester

in 1981, his Ph.D. in Business from the University of Rochester in 1983, and is a

New Zealand CPA. In New Zealand, Professor Healy worked for Arthur Young and ICI.

Prior to joining Harvard, Professor Healy spent fourteen years on the faculty at the M.I.T.

Sloan School of Management, where he received awards for teaching excellence in 1991,

1992, and 1997. In 1993–94 he served as Deputy Dean at the Sloan School, and in 1994–95

he was a visiting professor at London Business School and Harvard Business School.

Professor Healy’s research includes studies of the performance of financial analysts, corporate

governance, the performance of mergers, corporate disclosure, and managers’ financial reporting

decisions. His work has been published in leading journals in accounting and finance. In 1990, his

article “The Effect of Bonus Schemes on Accounting Decisions,” published in Journal of Account-

ing and Economics, was awarded the AICPA/AAA Notable Contribution Award. His text Busi-

ness Analysis and Valuation was awarded the AICPA/AAA’s Wildman Medal for contributions

to the practice in 1997, and the AICPA/AAA Notable Contribution Award in 1998.

ix

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CONTENTS

PART 1 FRAMEWORK

Chapter 1 A Framework for Business Analysis and Valuation

Using Financial Statements

1-3

The Role of Financial Reporting in Capital Markets 1-4

From Business Activities to Financial Statements 1-6

Influences of the Accounting System on Information Quality 1-6

Feature 1: Accrual Accounting 1-6

Feature 2: Accounting Conventions and Standards 1-7

Feature 3: Managers’ Reporting Strategy 1-8

Feature 4: Auditing 1-9

From Financial Statements to Business Analysis 1-10

Analysis Step 1: Business Strategy Analysis 1-11

Analysis Step 2: Accounting Analysis 1-12

Analysis Step 3: Financial Analysis 1-12

Analysis Step 4: Prospective Analysis 1-12

Summary 1-13

Discussion Questions 1-13

Notes 1-14

PART 2 BUSINESS ANALYSIS AND VALUATION TOOLS

Chapter 2 Strategy Analysis

2-3

Industry Analysis 2-3

Degree of Actual and Potential Competition 2-4

Bargaining Power in Input and Output Markets 2-7

Applying Industry Analysis: The U.S. Retail Department Store Industry 2-8

Competition in the U.S. Retail Department Store Industry 2-8

The Power of Buyers and Suppliers 2-10

Limitations of Industry Analysis 2-11

Competitive Strategy Analysis 2-11

Sources of Competitive Advantage 2-12

Achieving Competitive Advantage 2-13

Sustaining Competitive Advantage 2-13

Applying Competitive Strategy Analysis 2-14

x

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Corporate Strategy Analysis 2-16

Sources of Value Creation at the Corporate Level 2-17

Applying Corporate Strategy Analysis 2-18

Summary 2-21

Discussion Questions 2-22

Notes 2-23

Chapter 3 Overview of Accounting Analysis 3-1

The Institutional Framework for Financial Reporting 3-1

Accrual Accounting 3-1

Delegation of Reporting to Management 3-2

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles 3-3

External Auditing 3-5

Legal Liability 3-6

Factors Influencing Accounting Quality 3-6

Noise from Accounting Rules 3-7

Forecast Errors 3-7

Managers’ Accounting Choices 3-7

Steps in Performing Accounting Analysis 3-9

Step 1: Identify Principal Accounting Policies 3-9

Step 2: Assess Accounting Flexibility 3-9

Step 3: Evaluate Accounting Strategy 3-10

Step 4: Evaluate the Quality of Disclosure 3-10

Step 5: Identify Potential Red Flags 3-12

Step 6: Undo Accounting Distortions 3-13

Accounting Analysis Pitfalls 3-14

1. Conservative Accounting Is Not “Good” Accounting 3-14

2. Not All Unusual Accounting Is Questionable 3-14

Value of Accounting Data and Accounting Analysis 3-15

Summary 3-16

Discussion Questions 3-16

Notes 3-17

Chapter 4 Implementing Accounting Analysis 4-1

Recasting Financial Statements 4-2

Making Accounting Adjustments 4-7

Asset Distortions 4-7

Liability Distortions 4-20

Equity Distortions 4-23

Comparing Companies Using U.S. GAAP and IFRS 4-24

Application to TJX and Nordstrom 4-28

Contents xi

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Summary 4-30

Discussion Questions 4-31

Notes 4-36

Appendix A: Recasting Financial Statements into Standardized

Templates

4-37

Appendix B: Nordstrom, Inc. Operating Lease Adjustment 4-45

Chapter 5 Financial Analysis 5-1

Ratio Analysis 5-1

Measuring Overall Profitability 5-3

Decomposing Profitability: Traditional Approach 5-4

Decomposing Profitability: Alternative Approach 5-6

Assessing Operating Management: Decomposing Net Profit Margins 5-8

Gross Profit Margins 5-9

Selling, General, and Administrative Expenses 5-10

Tax Expense 5-11

Evaluating Investment Management: Decomposing Asset Turnover 5-12

Working Capital Management 5-12

Long-Term Assets Management 5-13

Evaluating Financial Management: Analyzing Financial Leverage 5-15

Current Liabilities and Short-Term Liquidity 5-16

Debt and Long-Term Solvency 5-17

Ratios of Disaggregated Data 5-19

Putting It All Together: Assessing Sustainable Growth Rate 5-20

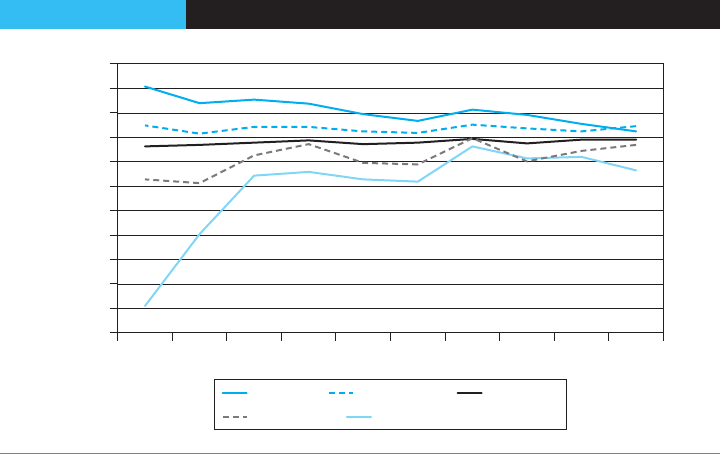

Historical Patterns of Ratios for U.S. Firms 5-21

Cash Flow Analysis 5-22

Cash Flow and Funds Flow Statements 5-22

Analyzing Cash Flow Information 5-24

Analysis of TJX’s and Nordstrom’s Cash Flow 5-27

Summary 5-27

Discussion Questions 5-28

Notes 5-29

Appendix A: The TJX Companies, Inc. Financial Statements 5-31

Appendix B: Nordstrom, Inc. Financial Statements 5-37

Chapter 6 Prospective Analysis: Forecasting 6-1

The Overall Structure of the Forecast 6-1

A Practical Framework for Forecasting 6-2

Performance Behavior: A Starting Point 6-3

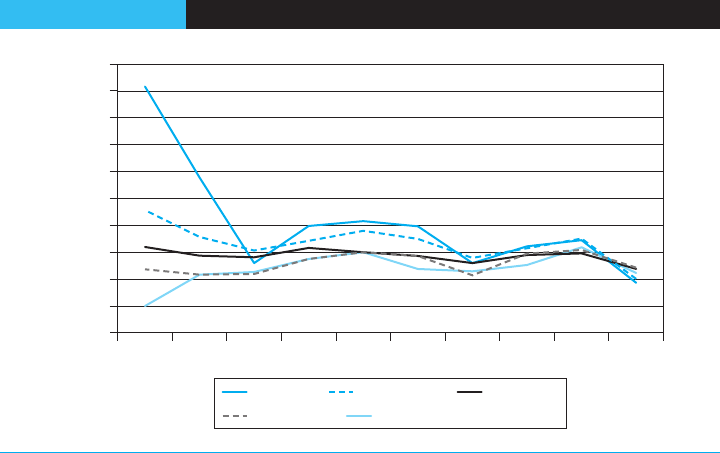

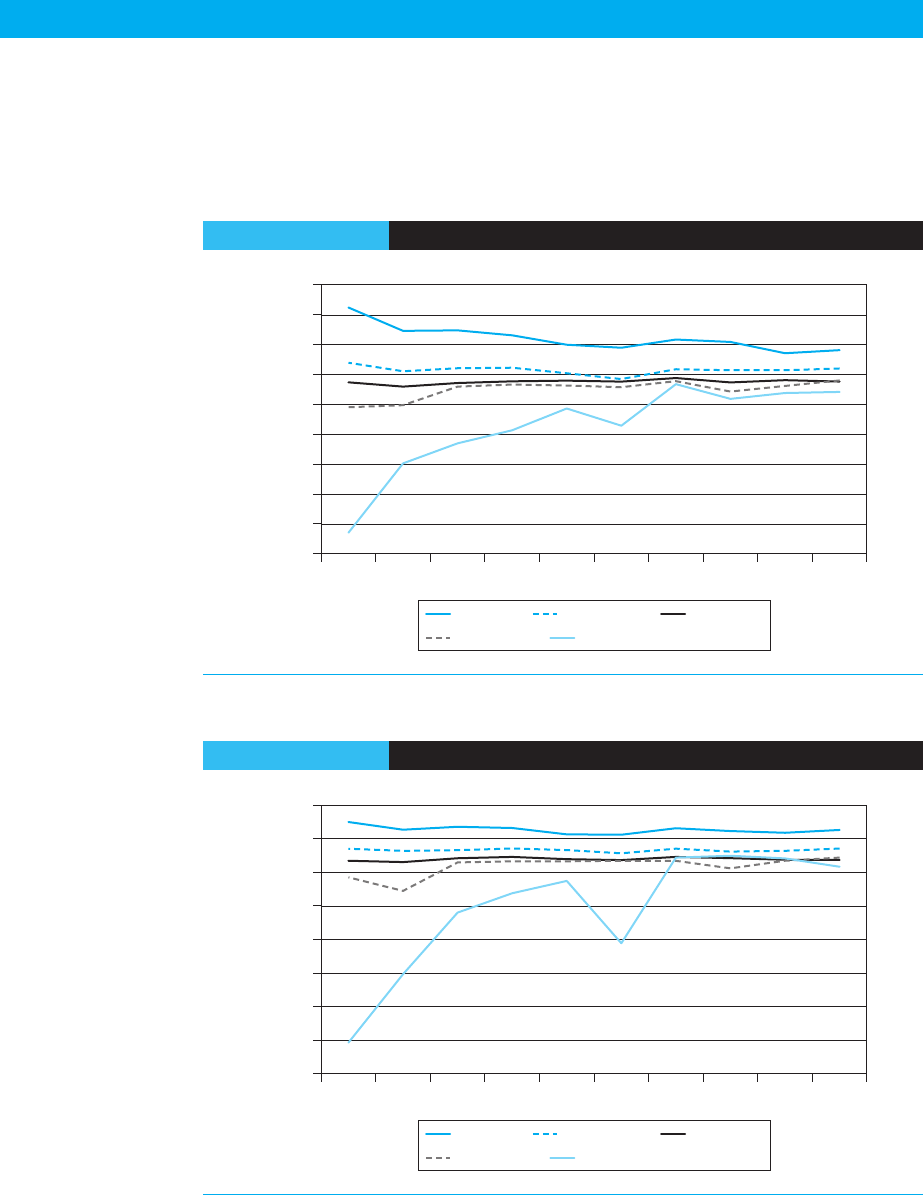

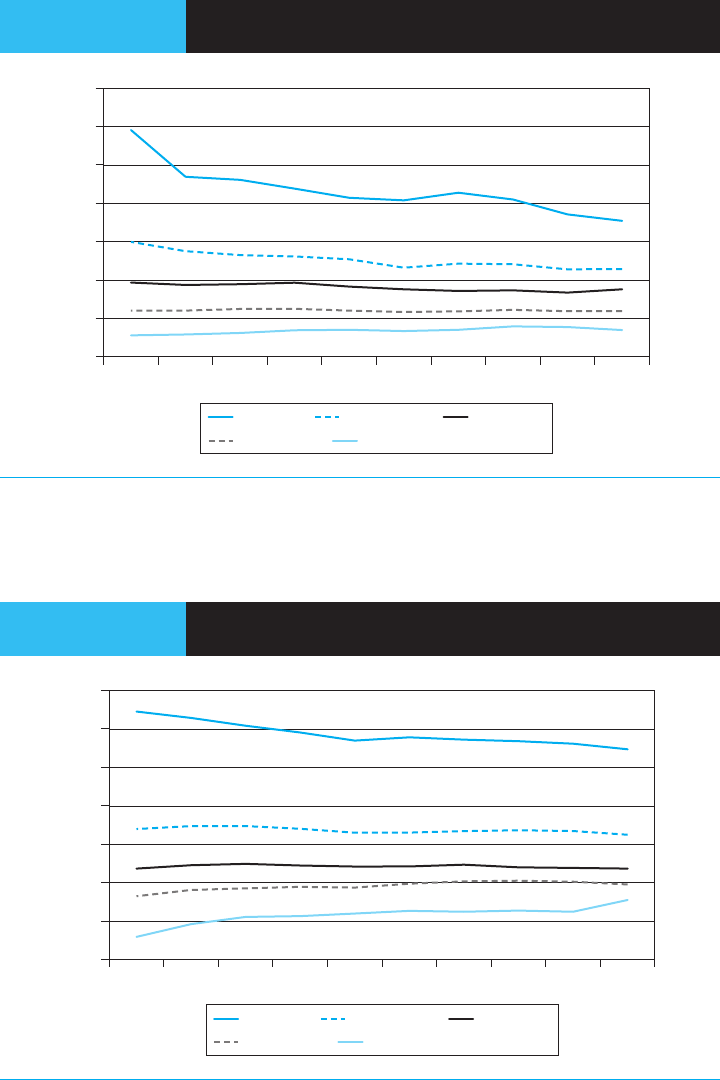

Sales Growth Behavior 6-3

Earnings Behavior 6-4

xii Contents

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Return on Equity Behavior 6-5

The Behavior of Components of ROE 6-6

Other Forecasting Considerations 6-7

Strategy, Accounting, and Financial Analysis and Forecasting 6-7

Macroeconomic Factors and Forecasting 6-8

Making Forecasts 6-8

Developing a Sales Growth Forecast 6-9

Developing a NOPAT Margin Forecast 6-11

Developing a Working Capital to Sales Forecast 6-12

Developing a Long-Term Assets to Sales Forecast 6-12

Developing a Capital Structure Forecast 6-12

Cash Flow Forecasts 6-13

Sensitivity Analysis 6-13

Seasonality and Interim Forecasts 6-15

Summary 6-16

Discussion Questions 6-17

Notes 6-18

Appendix: The Behavior of Components of ROE 6-20

Chapter 7 Prospective Analysis: Valuation Theory

and Concepts

7-1

Valuation Using Price Multiples 7-2

Key Issues with Multiples-Based Valuation 7-2

The Discounted Dividend Valuation Method 7-3

The Discounted Abnormal Earnings Valuation Method 7-4

Accounting Methods and Discounted Abnormal Earnings 7-5

Revisiting Price Multiple Valuations 7-7

Value-to-Book Equity Multiple 7-7

Value-to-Earnings Multiple 7-8

Shortcut Forms of Earnings-Based Valuation 7-10

Abnormal Earnings Simplification 7-10

ROE and Growth Simplifications 7-11

The Discounted Cash Flow Model 7-12

Comparing Valuation Methods 7-13

Differences in Focus 7-13

Differences in Required Structure 7-13

Differences in Terminal Value Implications 7-14

Summary 7-15

Discussion Questions 7-16

Notes 7-17

Contents xiii

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Appendix A: Time Value of Money: Present and Future Values 7-18

Appendix B: Valuation Formulas 7-21

Appendix C: Reconciling the Discounted Dividends and Discounted

Abnormal Earnings Models

7-21

Appendix D: Asset Valuation Methodologies 7-22

Chapter 8 Prospective Analysis: Valuation Implementation 8-1

Detailed Forecasts of Performance 8-1

Making Performance Forecasts for Valuing TJX 8-2

Terminal Values 8-2

Terminal Values with the Competitive Equilibrium Assumption 8-4

Competitive Equilibrium Assumption Only on Incremental Sales 8-5

Terminal Value with Persistent Abnormal Performance and Growth 8-5

Terminal Value Based on a Price Multiple 8-6

Selecting the Terminal Year 8-6

Estimates of TJX’s Terminal Value 8-7

Computing a Discount Rate 8-8

Estimating TJX’s Cost of Equity 8-10

Adjusting Cost of Equity for Changes in Leverage 8-10

Computing Equity Value 8-11

Value Estimates Versus Market Values 8-12

Sensitivity Analysis 8-13

Some Practical Issues in Valuation 8-13

Dealing with Accounting Distortions 8-13

Dealing with Negative Book Values 8-14

Dealing with Excess Cash and Excess Cash Flow 8-14

Summary 8-15

Discussion Questions 8-15

Notes 8-16

Appendix: Estimating TJX’s Overall Asset Value 8-17

PART 3 BUSINESS ANALYSIS AND VALUATION

APPLICATIONS

Chapter 9 Equity Security Analysis 9-3

Investor Objectives and Investment Vehicles 9-4

Equity Security Analysis and Market Efficiency 9-5

Market Efficiency and the Role of Financial Statement Analysis 9-6

Market Efficiency and Managers’ Financial Reporting Strategies 9-6

Evidence of Market Efficiency 9-6

xiv Contents

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Approaches to Fund Management and Securities Analysis 9-7

Active Versus Passive Management 9-7

Quantitative Versus Traditional Fundamental Analysis 9-7

Formal Versus Informal Valuation 9-8

The Process of Comprehensive Security Analysis 9-8

Selection of Candidates for Analysis 9-8

Inferring Market Expectations 9-9

Developing the Analyst’s Expectations 9-11

The Final Product of Security Analysis 9-12

Performance of Security Analysts and Fund Managers 9-13

Performance of Sell-Side Analysts 9-13

Performance of Fund Managers 9-14

Summary 9-15

Discussion Questions 9-15

Notes 9-17

Chapter 10 Credit Analysis and Distress Prediction 10-1

Why do Firms Use Debt Financing? 10-2

The Market for Credit 10-3

Commercial Banks 10-3

Non-Bank Financial Institutions 10-4

Public Debt Markets 10-4

Sellers Who Provide Financing 10-4

The Credit Analysis Process in Private Debt Markets 10-5

Step 1: Consider the Nature and Purpose of the

Loan

10-5

Step 2: Consider the Type of Loan and Available

Security

10-6

Step 3: Conduct a Financial Analysis of the

Potential Borrower

10-7

Step 4: Assemble the Detailed Loan Structure, Including

Loan Covenants

10-8

Financial Statement Analysis and Public Debt 10-10

The Meaning of Debt Ratings 10-10

Factors That Drive Debt Ratings 10-12

Prediction of Distress and Turnaround 10-14

Models for Distress Prediction 10-15

Investment Opportunities in Distressed Companies 10-16

Credit Ratings and the Subprime Crisis 10-16

Summary 10-18

Discussion Questions 10-19

Notes 10-20

Contents xv

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Chapter 11 Mergers and Acquisitions 11-1

Motivation for Merger or Acquisition 11-2

Motivation for Pfizer’s Acquisition of Wyeth 11-4

Acquisition Pricing 11-5

Analyzing Premium Offered to Target Stockholders 11-6

Analyzing Value of the Target to the Acquirer 11-7

Earnings Multiples 11-7

Discounted Abnormal Earnings or Cash Flows 11-8

Pfizer’s Pricing of Wyeth 11-10

Acquisition Financing and Form of Payment 11-11

Effect of Form of Payment on Acquiring Stockholders 11-11

Capital Structure Effects of Form of Financing 11-11

Information Problems and the Form of Financing 11-12

Control and the Form of Payment 11-12

Effect of Form of Payment on Target Stockholders 11-13

Tax Effects of Different Forms of Consideration 11-13

Transaction Costs and the Form of Payment 11-13

Pfizer’s Financing of Wyeth 11-14

Acquisition Outcome 11-14

Other Potential Acquirers 11-14

Target Management Entrenchment 11-15

Antitrust and Security Issues 11-16

Analysis of Outcome of Pfizer’s Offer for Wyeth 11-17

Summary 11-17

Discussion Questions 11-18

Notes 11-19

Chapter 12 Communication and Governance 12-1

Governance Overview 12-2

Management Communication with Investors 12-4

A Word of Caution 12-5

Example: Communication Issues for Jefferies Group, Inc. 12-5

Communication Through Financial Reporting 12-6

Accounting as a Means of Management Communication 12-7

Factors That Increase the Credibility of Accounting Communication 12-7

Accounting Standards and Auditing 12-7

Monitoring by Financial Analysts and Ratings Agencies 12-7

Management Reputation 12-8

Limitations of Financial Reporting for Investor Communication 12-8

Accounting Rule Limitations 12-8

Auditor, Analyst, and other Intermediary Limitations 12-8

xvi Contents

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Management Credibility Problems 12-9

Example: Accounting Communication for Jefferies 12-9

Communication Through Financial Policies 12-10

Dividend Payout Policies 12-10

Stock Repurchases 12-10

Financing Choices 12-11

Hedging 12-11

Example: Financial Policies at Jefferies 12-12

Alternate Forms of Investor Communication 12-13

Analyst Meetings 12-13

Voluntary Disclosure 12-13

Example: Other Forms of Communication at Jefferies 12-14

The Role of the Auditor 12-15

Role of Financial Analysis Tools in Auditing 12-16

Example: Auditing Jefferies 12-17

The Role of the Audit Committee in the United States 12-18

Summary 12-19

Discussion Questions 12-20

Notes 12-21

Subject Index I-1

Name Index I-9

Contents xvii

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

PART

1

FRAMEWORK

CHAPTER 1

A Framework for Business Analysis and Valuation

Using Financial Statements

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Chapter

1

A FRAMEWORK FOR

BUSINESS ANALYSIS

AND VALUATION USING

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

T

his chapter outlines a comprehensive framework for financial statement analysis.

Because financial statements provide the most widely available data on public

corporations’ economic activities, investors and other stakeholders rely on

financial reports to assess the plans and performance of firms and corporate managers.

A variety of questions can be addressed by business analysis using financial

statements, as shown in the following examples:

• A security analyst may be interested in asking: “How well is the firm I am follow-

ing performing? Did the firm meet my performance expectations? If not, why not?

What is the value of the firm’s stock given my assessment of the firm’s current and

future performance?”

• A loan officer may need to ask: “What is the credit risk involved in lending a cer-

tain amount of money to this firm? How well is the firm managing its liquidity

and solvency? What is the firm’s business risk? What is the additional risk created

by the firm’s financing and dividend policies?”

• A management consultant might ask: “What is the structure of the industry in

which the firm is operating? What are the strategies pursued by various players

in the industry? How have these factors affected the relative performance of differ-

ent firms in the industry?”

• A corporate manager may ask: “Is my firm properly valued by investors? Is our

investor communication program adequate to facilitate this process?” or “Is this

firm a potential takeover target? How much value can be added if we acquire this

firm? How can we finance the acquisition?”

• An independent auditor would want to ask: “Are the accounting policies and

accrual estimates in this company ’s financial statements consistent with my under-

standing of this business and its recent performance? Do these financial reports

communicate the current status and significant risks of the business?”

The structure of state economies during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries has

generally fallen into one of two distinct and broad ideologies for channeling savings into

business investments—capitalism and central planning. The capitalist market model broadly

relies on the market mechanism to govern economic activity, and decisions regarding

investments are made privately. Centrally planned economies have used central planning and

government agencies to pool national savings and to direct investments in business enterprises.

The failure of the central planning model is evident from the fact that at this point most of

1-3

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

these economies have partly or entirely abandoned it in favor of the market model. As a result,

in almost all countries in the world today, capital markets play an important role in channeling

financial resources from savers to business enterprises that need capital.

Financial statement analysis is a valuable activity when managers have in-depth

information on a firm’s strategies and performance and a variety of institutional factors

make it unlikely that they fully disclose this information. In this setting, outside analysts

attempt to create “inside information” from analyzing financial statement data, thereby

gaining valuable insights about the firm’s current performance and future prospects.

To understand the contribution that financial statement analysis can make, it is important

to understand the role of financial reporting in the functioning of capital markets and the

institutional forces that shape financial statements. Therefore, we first present a brief

description of these forces followed by a discussion of the steps that an analyst must

perform to extract information from financial statements and provide meaningful forecasts.

THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL REPORTING IN CAPITAL MARKETS

A critical challenge for any economy is the allocation of savings to investment opportu-

nities. Economies that do this well can exploit new business ideas to spur innovation and

create jobs and wealth at a rapid pace. In contrast, economies that manage this process

poorly tend to dissipate their wealth and fail to support business opportunities.

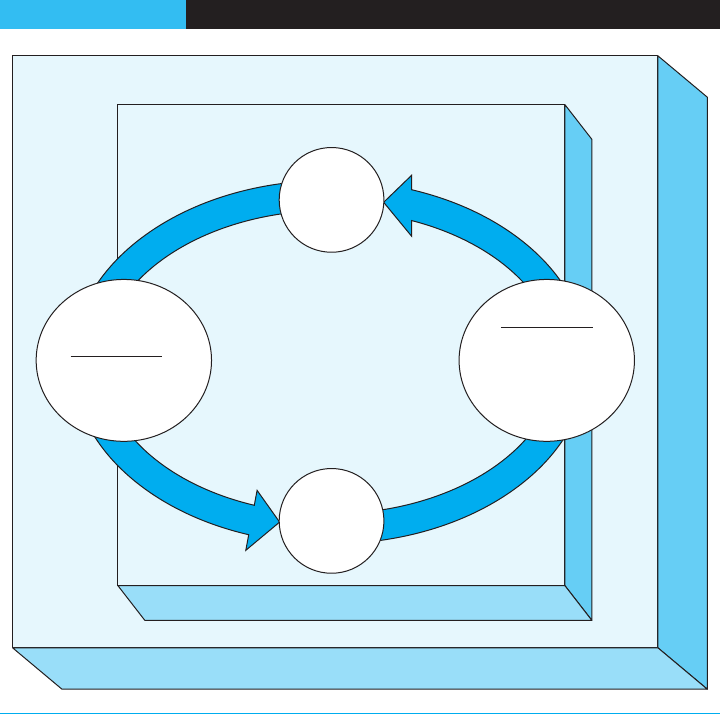

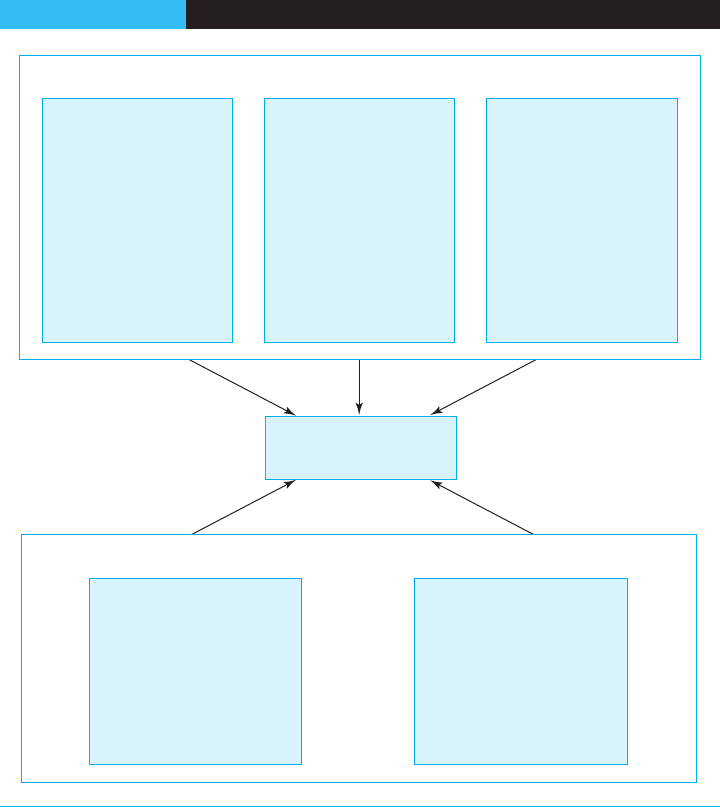

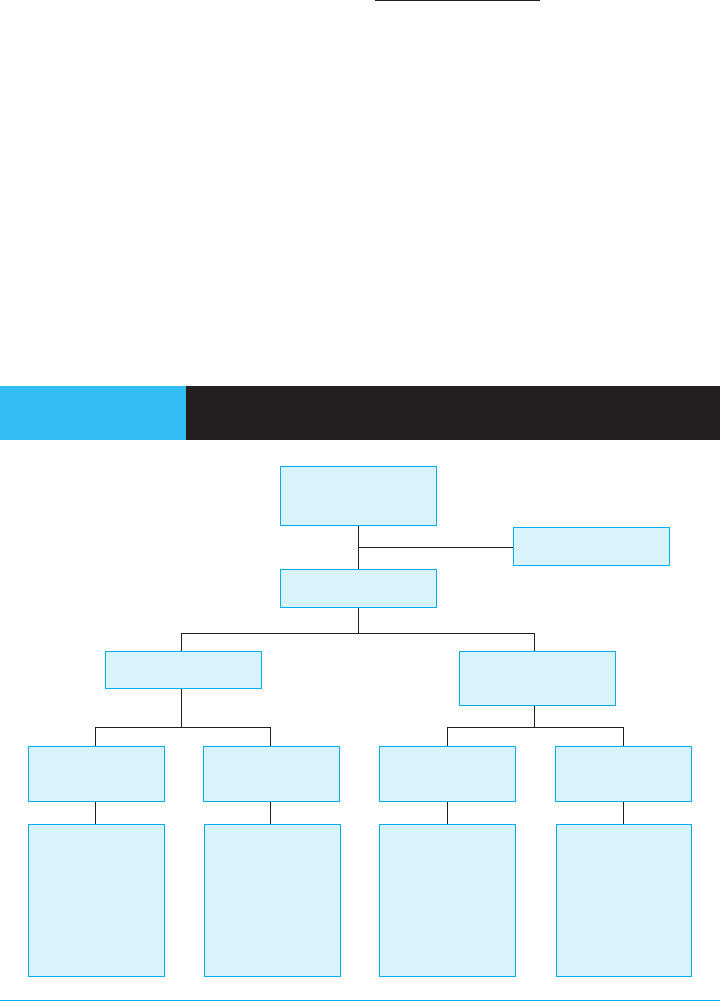

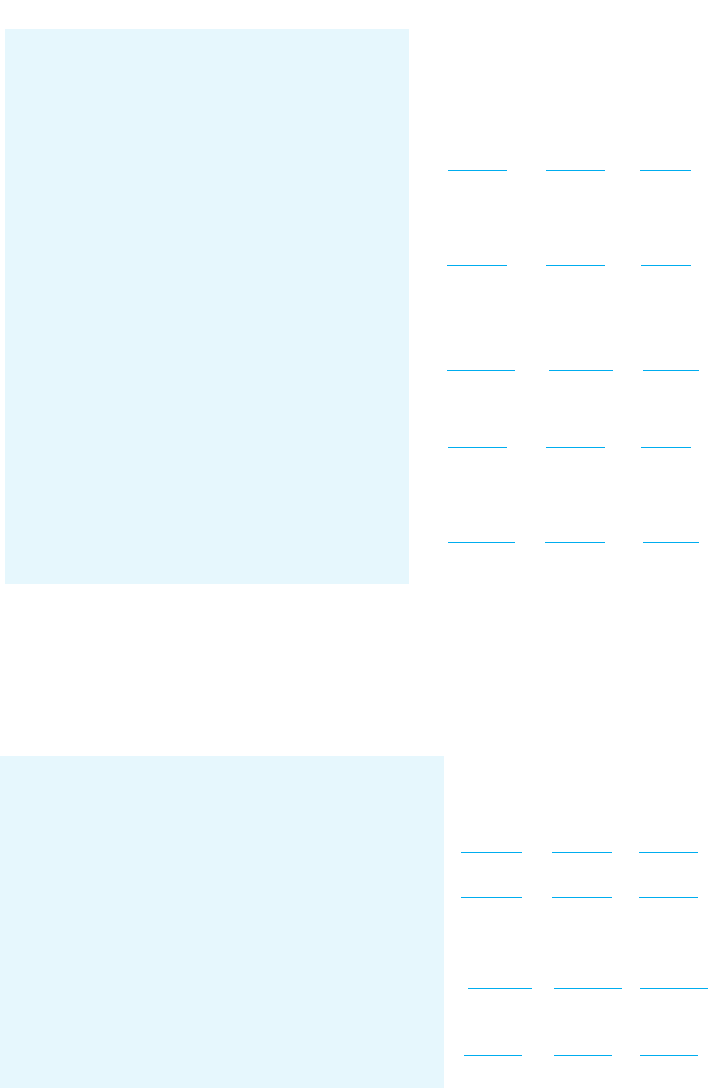

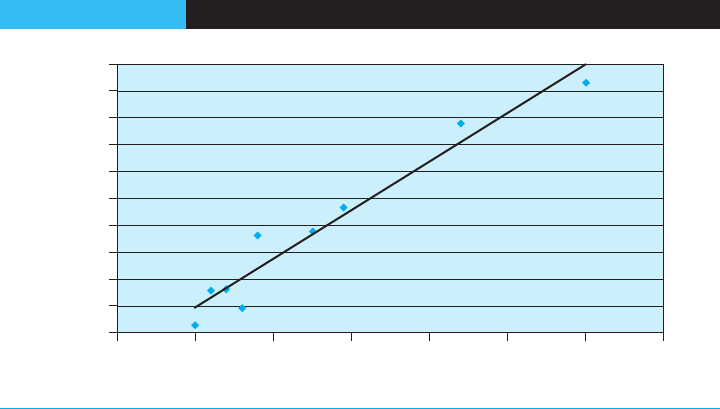

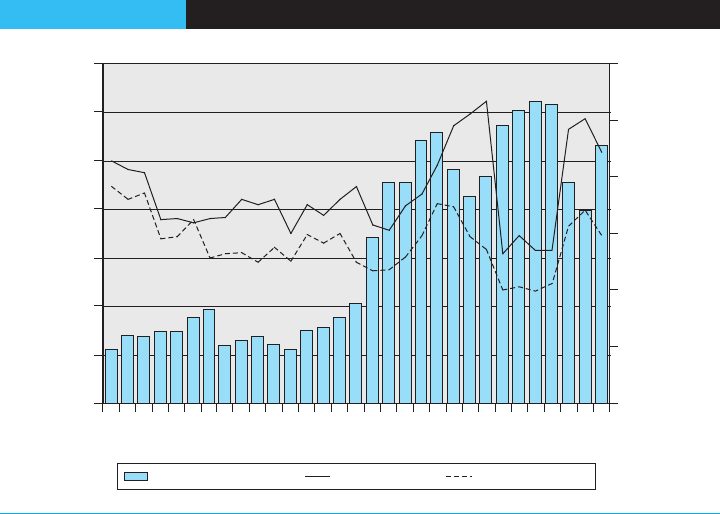

Figure 1-1 provides a schematic representation of how capital markets typically work in a

broad sense. Savings in an economy are widely distributed among households. There are

usually many new entrepreneurs and existing companies that would like to attract these sav-

ings to fund their business ideas. While both savers and entrepreneurs would like to do busi-

ness with each other, matching savings to business investment opportunities is complicated

for at least three reasons. First, entrepreneurs typically have better information than savers

on the value of business investment opportunities. Second, communication by entrepreneurs

to investors is not completely credible because investors know entrepreneurs have an incen-

tive to inflate the value of their ideas. Third, savers generally lack the financial sophistication

needed to analyze and differentiate among the various business opportunities.

These information and incentive problems lead to what economists call the “lemons”

problem, which can potentially break down the functioning of capital markets.

1

It works

like this: Consider a situation where half the business ideas are “good” and the other half are

“bad.” If investors cannot distinguish between the two types of business ideas, entrepreneurs

with bad ideas will try to claim that their ideas are as valuable as the good ideas. Realizing this

possibility, investors value both good and bad ideas at an average level. Unfortunately, this

penalizes good ideas, and entrepreneurs with good ideas find the terms on which they can

get financing to be unattractive. As these entrepreneurs leave the capital market, the propor-

tion of bad ideas in the market increases. Over time, bad ideas “crowd out” good ideas, and

investors lose confidence in this market.

The emergence of the institutions that make up a fully formed capital market system

can prevent such a market breakdown. Financial intermediaries such as venture capital

and private equity firms, banks, mutual funds, and insurance companies focus on aggre-

gating funds from individual investors and distributing those funds to businesses seeking

sources of capital. Information intermediaries such as auditors and company audit com-

mittees serve as credibility enhancers to provide an independent assessment of business

claims. Information analyzers and advisors such as financial analysts, credit rating agen-

cies and the financial press are another type of information intermediary that collect and

analyze business information used to make business decisions. Transaction facilitators

such as stock exchanges and brokerage houses play a crucial role in capital markets by

providing a platform that facilitates buying and selling in markets. Finally, regulators

1-4

PART 1 • Framework

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Accounting

Standards Board (FASB) in the United States create appropriate regulatory policy that

establishes the legal framework of the capital market system, while adjudicators such as

the court system resolve disputes that arise between participants.

2

In a well-functioning

capital market, the market institutions described above add value by both helping inves-

tors distinguish good investment opportunities from bad ones and by directing funding

to those business ideas deemed most promising.

Financial reporting plays a critical role in the effective functioning of the capital markets.

Information intermediaries attempt to add value by either enhancing the credibility of finan-

cial reports (as auditors do) or by analyzing the information in financial statements (as ana-

lysts and the rating agencies do). Financial intermediaries rely on the information in financial

statements to analyze investment opportunities, and they supplement this with information

from other sources, including the analysis and perspective of the information intermediaries.

Ideally, the different intermediaries serve as a system of checks and balances to ensure

the efficient functioning of the capital markets system. However, this is not always the

case, as on occasion they mutually reinforce rather than counterbalance each other. This

can arise from imperfections in financial and information intermediaries’ incentives, gover-

nance issues within the intermediary organizations themselves, and conflicts of interest, as

evidenced by the spectacular failures of companies such as Enron and WorldCom in the

FIGURE 1- 1 Capital Markets

Regulators/Adjudicators

Capital Markets

Savings

Transaction Facilitators

Transaction Platform

Business

Ideas

Financial

Intermediaries

–Aggregators and

Distributors

Information

Intermediaries

–Credibility

Enhancers

–Information

Analyzers and

Advisors

Source: © Cengage Learning

A Framework for Business Analysis and Valuation Using Financial Statements 1-5

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

early part of the new century,

3

and more recently companies such as Lehman Brothers,

New Century Financial, and a host of others during the recent global financial crisis.

The examples above demonstrate that while this market mechanism over time has

been seen to function efficiently with prices reflecting all available information on a par-

ticular investment, individual securities may still be mispriced, thereby justifying the

need for financial statement analysis.

In the following section, we discuss key aspects of the financial reporting system design

that enable it to effectively play this vital role in the functioning of the capital markets.

FROM BUSINESS A CTIV ITIES TO FINANCIAL STATEME NTS

Corporate managers are responsible for acquiring physical and financial resources from

the firm’s environment and using them to create value for the firm’s investors. Value is

created when the firm earns a return on its investment in excess of the cost of capital.

Managers formulate business strategies to achieve this goal, and they implement them

through business activities. A firm’s business activities are influenced by its economic

environment and its own business strategy. The economic environment includes the

firm’s industry, its input and output markets, and the regulations under which the firm

operates. The firm’ s business strategy determines how the firm positions itself in its envi-

ronment to achieve a competitive advantage.

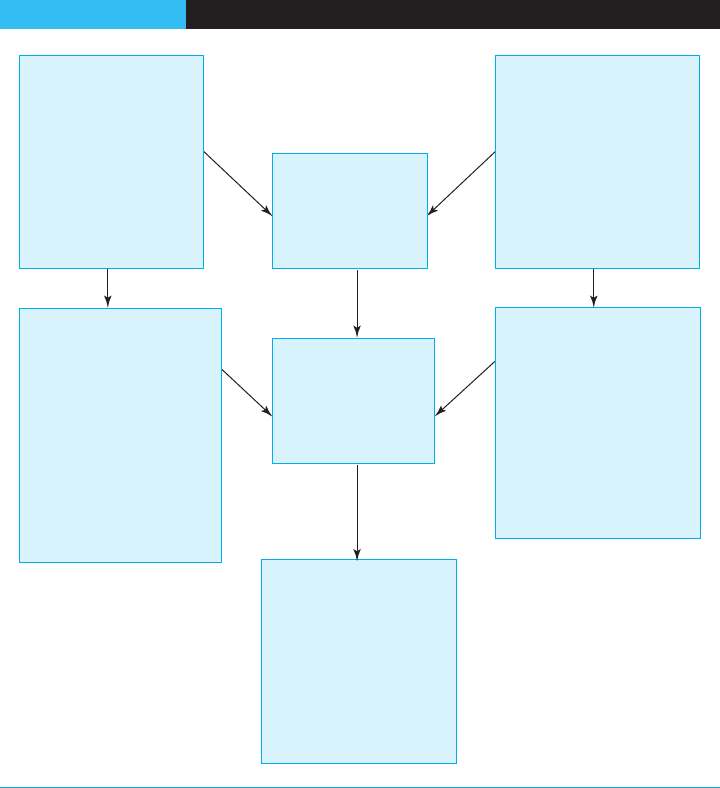

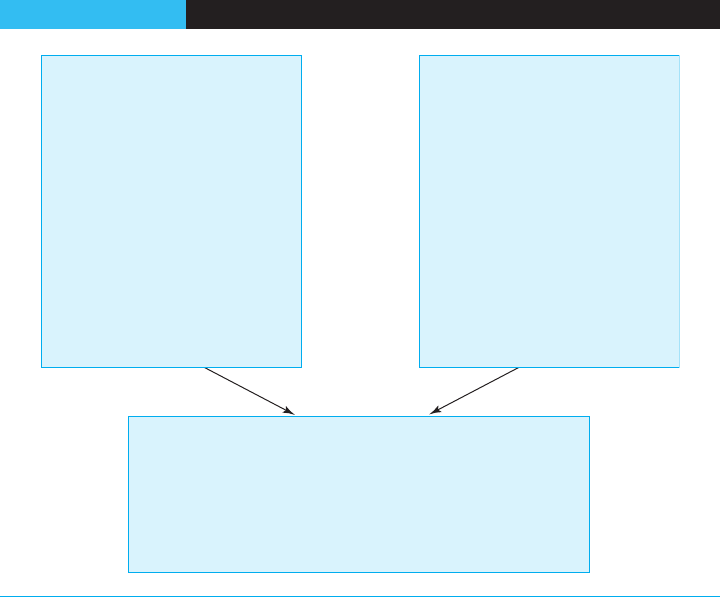

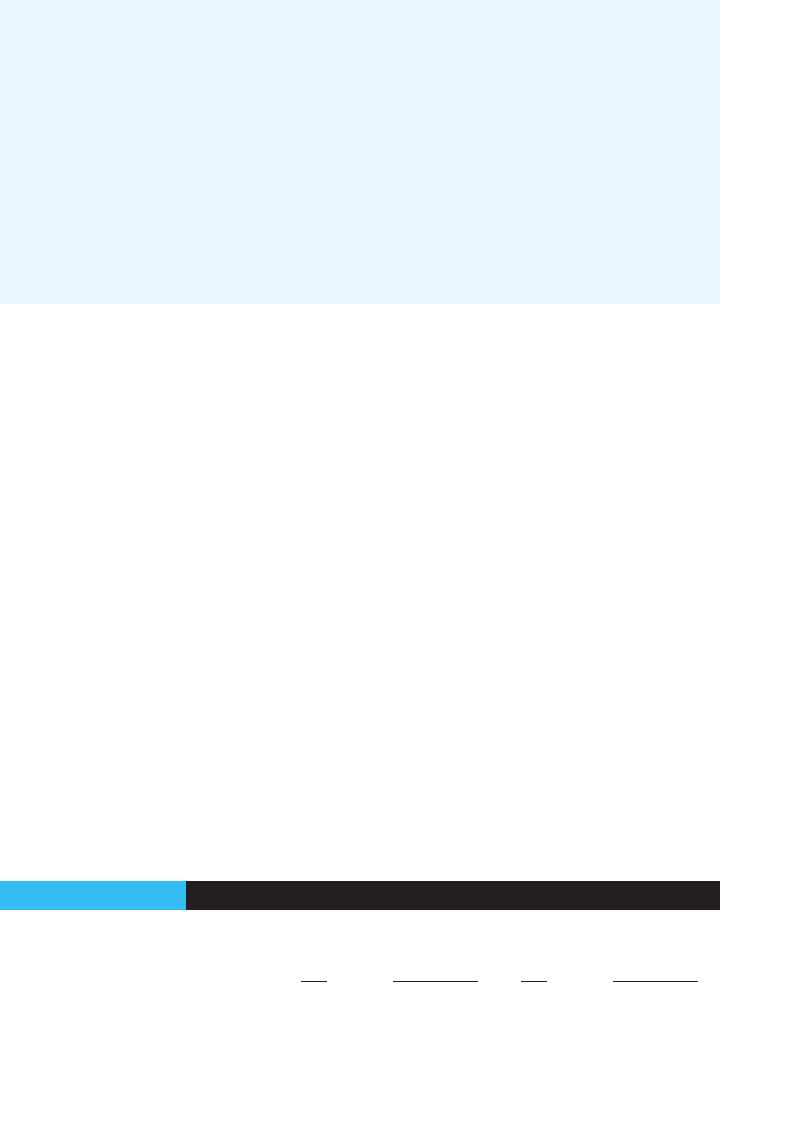

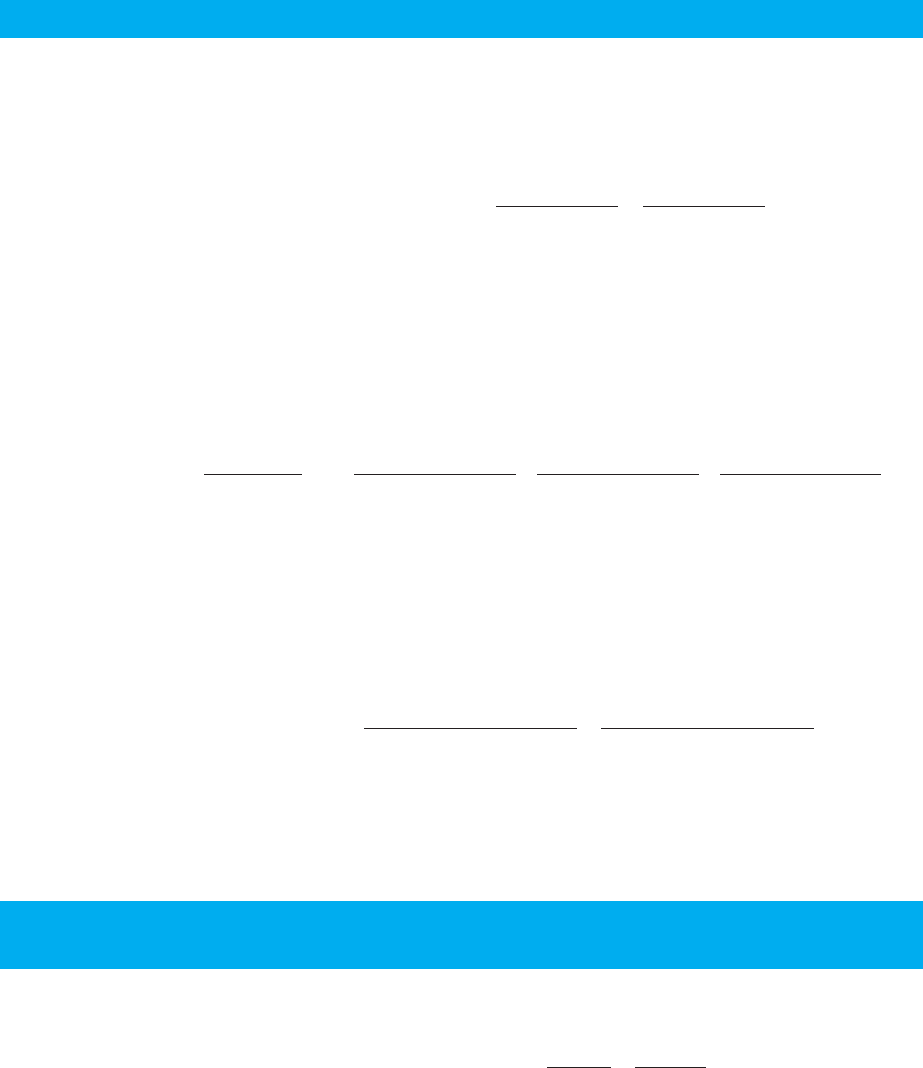

As shown in Figure 1-2, a firm’s financial statements summarize the economic conse-

quences of its business activities. The firm’s business activities in any time period are too

numerous to be reported individually to outsiders. Further, some of the activities under-

taken by the firm are proprietary in nature, and disclosing these in detail could be a det-

riment to the firm’s competitive position. The accounting system provides a mechanism

through which business activities are selected, measured, and aggregated into financial

statement data.

INFLUENCES OF T HE ACCOUNTING SYSTEM

ON INFORMATION QUALITY

Intermediaries using financial statement data to do business analysis have to be aware

that financial reports are influenced both by the firm’s business activities and by its

accounting system. A key aspect of financial statement analysis, therefore, involves under-

standing the influence of the accounting system on the quality of the financial statement

data being used in the analysis. The institutional features of accounting systems discussed

below determine the extent of that influence.

Feat ure 1: Accrual Accounting

One of the fundamental features of corporate financial reports is that they are prepared

using accrual rather than cash accounting. Unlike cash accounting, accrual accounting

distinguishes between the recording of costs and benefits associated with economic activ-

ities and the actual payment and receipt of cash. Net income is the primary periodic per-

formance index under accrual accounting. To compute net income, the effects of

economic transactions are recorded on the basis of expected, not necessarily actual, cash

receipts and payments. Expected cash receipts from the delivery of products or services

are recognized as revenues, and expected cash outflows associated with these revenues

are recognized as expenses.

The need for accrual accounting arises from investors’ demand for financial reports

on a periodic basis. Because firms undertake economic transactions on a continual

1-6

PART 1 • Framework

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

basis, the arbitrary closing of accounting books at the end of a reporting period leads to a

fundamental measurement problem. Since cash accounting does not report the full eco-

nomic consequence of the transactions undertaken in a given period, accrual accounting

is designed to provide more complete information on a firm ’s periodic performance.

Feature 2: Accounting Conventions and Standards

The use of accrual accounting lies at the center of many important complexities in cor-

porate financial reporting. Because accrual accounting deals with expectations of future

cash consequences of current events, it is subjective and relies on a variety of assump-

tions. Who should be charged with the primary responsibility of making these ass-

umptions? In the current system, a firm’s managers are entrusted with the task of

making the appropriate estimates and assumptions to prepare the financial statements

because they have intimate knowledge of their firm’s business.

The accounting discretion granted to managers is potentially valuable because it

allows them to reflect inside information in reported financial statements. However,

FIGURE 1- 2 From Business Activities to Financial Statements

Business Environment

Labor markets

Capital markets

Product markets:

Suppliers

Customers

Competitors

Business regulations

Business Activities

Operating activities

Investment activities

Financing activities

Accounting System

Measure and report

economic

consequences of

business activities.

Financial Statements

Managers’ superior

information on

business activities

Estimation errors

Distortions from man-

agers’ accounting

choices

Business Strategy

Scope of business:

Degree of diversication

Type of diversication

Competitive positioning:

Cost leadership

Differentiation

Key success factors and

risks

Accounting Strategy

Choice of accounting

policies

Choice of accounting

estimates

Choice of reporting format

Choice of supplementary

disclosures

Accounting Environment

Capital market structure

Contracting and

governance

Accounting conventions

and regulations

Tax and nancial

accounting linkages

Third-party auditing

Legal system for

accounting disputes

Source: © Cengage Learning

A Framework for Business Analysis and Valuation Using Financial Statements 1-7

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

since investors view profits as a measure of managers’ performance, managers have

incentives to use their accounting discretion to distort reported profits by making biased

assumptions. Further, the use of accounting numbers in contracts between the firm and

outsiders provides another motivation for management manipulation of accounting

numbers. Income management distorts financial accounting data, making them less valu-

able to external users of financial statements. Therefore, the delegation of financial

reporting decisions to corporate managers has both costs and benefits.

A number of accounting conventions have evolved to ensure that managers use their

accounting flexibility to summarize their knowledge of the firm’s business activities

and not disguise reality for self-serving purposes. For example, the measurability and

conservatism conventions are accounting responses to concerns about distortions from

managers’ potentially optimistic bias. Both these conventions attempt to limit managers’

optimistic bias by imposing their own pessimistic bias.

Accounting standards, promulgated by the FASB in the United States and similar

standard-setting bodies in other countries, also limit potential distortions that managers

can introduce into reported numbers. These uniform standards, such as Generally

Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in the United States and the International Finan-

cial Reporting Standards (IFRS) internationally, attempt to reduce managers’ ability to

record similar economic transactions in dissimilar ways, either over time or across firms.

Increased uniformity from accounting standards, however, comes at the expense of

reduced flexibility for managers to reflect genuine business differences in their firms’

financial statements. Rigid accounting standards work best for economic transactions

whose accounting treatment is not predicated on managers’ proprietary information.

However, when there is significant business judgment involved in assessing a transac-

tion’s economic consequences, rigid standards that prevent managers from using their

superior business knowledge would be counterproductive. Further, if accounting stan-

dards are too rigid, they may induce managers to expend economic resources to restruc-

ture business transactions to achieve a desired accounting result.

Feature 3: Managers’ Repor ting Strategy

Because the mechanisms that limit managers’ ability to distort accounting data add

noise, it is not optimal to use accounting regulation to eliminate managerial flexibility

completely. Therefore, real-world accounting systems leave considerable room for man-

agers to influence financial statement data. A firm’s reporting strategy, i.e., the manner in

which managers use their accounting discretion, has an important influence on the firm’s

financial statements.

Corporate managers can choose accounting and disclosure policies that make it more

or less difficult for external users of financial reports to understand the true economic

picture of their businesses. Accounting rules often provide a broad set of alternatives

from which managers can choose. Further, managers are entrusted with making a range

of estimates in implementing these accounting policies. Accounting regulations usually

prescribe minimum disclosure requirements, but they do not restrict managers from vol-

untarily providing additional disclosures.

A superior disclosure strategy will enable managers to communicate the underlying

business reality to outside investors. One important constraint on a firm’s disclosure

strategy is the competitive dynamics in product markets. Disclosure of proprietary infor-

mation about business strategies and their expected economic consequences may hurt

the firm’s competitive position. Subject to this constraint, managers can use financial

statements to provide information useful to investors in assessing their firm’s true eco-

nomic performance.

1-8

PART 1 • Framework

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Managers can also use financial reporting strategies to manipulate investors’ percep-

tions. Using the discretion granted to them, managers can make it difficult for investors

to identify poor performance on a timely basis. For example, managers can choose

accounting policies and estimates to provide an optimistic assessment of the firm’s true

performance. They can also make it costly for investors to understand the true perfor-

mance by controlling the extent of information that is disclosed voluntarily.

The extent to which financial statements reveal the underlying business reality varies

across firms and across time for a given firm. This variation in accounting quality pro-

vides both an important opportunity and a challenge in doing business analysis.

The process through which analysts can separate noise from information in financial

statements, and gain valuable business insights from financial statement analysis, is dis-

cussed in the following section.

Feature 4: Auditing

Auditing, broadly defined as a verification of the integrity of the reported financial state-

ments by someone other than the preparer, ensures that managers use accounting rules

and conventions consistently over time and that their accounting estimates are reason-

able. Therefore, auditing improves the quality of accounting data.

Third-party auditing may also reduce the quality of financial reporting because it con-

strains the kind of accounting rules and conventions that evolve over time. For example,

the FASB considers the views of auditors in the standard-setting process. Auditors are

likely to argue against accounting standards producing numbers that are difficult to

audit, even if the proposed rules produce relevant information for investors.

The legal environment in which accounting disputes between managers, auditors, and

investors are adjudicated can also have a significant effect on the quality of reported

numbers. The threat of lawsuits and resulting penalties has the beneficial effect of

improving the accuracy of disclosure. However, the potential for a significant legal liabil-

ity might also discourage managers and auditors from supporting accounting proposals

requiring risky forecasts, such as forward-looking disclosures.

The governance structure of firms includes an audit committee of the board of direc-

tors. The audit committee is expected to be independent of management, and its key

roles include overseeing the work of the auditor and ensuring that financial statements

are properly prepared. This governance mechanism further serves to enhance the quality

and accountability of financial reporting.

LEGISLATION AFFECTING FINANCIAL REPORTING AND AUDITING

In the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 made important changes in

financial reporting and auditing. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act of 2010 introduced new regulations for the banking sector, including

several new requirements likely to affect financial reporting and auditing.

Sarbanes-Oxley Act

In the aftermath of the collapse of the dot-com bubble and high-profile accounting scandals

such as Enron and WorldCom, the U.S. Congress passed the bipartisan Sarbanes-Oxley Act

(SOX as it has come to be known) in July 2002. The margin by which the bill was enacted—

it passed by a vote of 424 to 3 in the House of Representatives and a vote of 99 to 0 in the

Senate—and the far-reaching nature of the reforms reflected the degree to which the pub-

lic’s confidence in the quality of corporate financial reporting had been undermined.

A Framework for Business Analysis and Valuation Using Financial Statements 1-9

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

SOX mandated certain fundamental changes to corporate governance as related to

financial reporting and altered the relationship between a firm and its auditor. Some of

the highlights included:

• Creation of a not-for-profit accounting oversight board, the Public Company

Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), to ensure standards for auditing and the

ethics and independence of public accounting firms;

• Mandating stricter guidelines for the composition and role of the audit committee

of the Board of Directors, including director independence and financial expertise;

• Enhancing corporate responsibility for financial reporting by requiring the CEO

and CFO to personally certify the appropriateness of periodic reports;

• Requiring management to assess and report on the adequacy of internal controls,

which then needs to be certified by the auditor;

• Providing greater whistleblower protection;

• Allowing for the imposition of stiffer penalties, including prison terms and fines,

for securities fraud;

• Prohibiting accounting firms from providing certain non-audit services contempo-

raneously with an audit and mandating audit partner rotation;

• Prescribing conflict of interest rules for equity research analysts; and

• Increasing the funding available to the Securities and Exchange Commission to

ensure compliance.

Since the adoption of SOX, similar legislation has been passed in Japan, the EU,

Canada, Israel, Australia, and France, among others, indicating general agreement on

the importance of tighter reporting standards.

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010

The Dodd-Frank Act was passed in 2010 in response to the financial crisis on Wall Street.

The new legislation mandated important new changes in the governance of banks, including:

• The creation of a new independent consumer protection agency to ensure that

consumers receive the information they need to shop for financial products;

• Increased monitoring of banks, including restrictions on proprietary trading;

• New procedures to facilitate the orderly liquidation of failed banks;

• Increased transparency of the trading of financial instruments, which should facili-

tate fair value accounting for these instruments;

• Increased oversight of ratings agencies;

• Provisions for shareholders to have a non-binding vote on executive compensa-

tion; and

• Increased disclosures on the assets underlying complex financial securities.

FROM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS TO BUSINESS ANALYSIS

Because managers’ insider knowledge is a source of both value and distortion in accounting

data, it is difficult for outside users of financial statements to separate information from

distortion and noise. Not being able to undo accounting distortions completely, investors

“discount” a firm’s reported accounting performance. In doing so, they make a probabilistic

assessment of the extent to which a firm’s reported numbers reflect its economic perfor-

mance. As a result, investors frequently have an imprecise assessment of an individual

firm’s performance. Financial and information intermediaries can add value by improving

investors’ understanding of a firm’s current performance and its future prospects.

1-10

PART 1 • Frame work

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Effective financial statement analysis is valuable because it attempts to get at man-

agers’ inside information from public financial statement data. Since intermediaries do

not have direct or complete access to this inside information, they rely on their knowl-

edge of the firm’s industry and its competitive strategies to interpret financial statements.

Successful intermediaries have at least as good an understanding of the industry econom-

ics as the firm’s managers do, as well as a reasonably good understanding of the firm’s

competitive strategy. Although outside analysts have an information disadvantage

relative to the firm’s managers, they are more objective in evaluating the economic con-

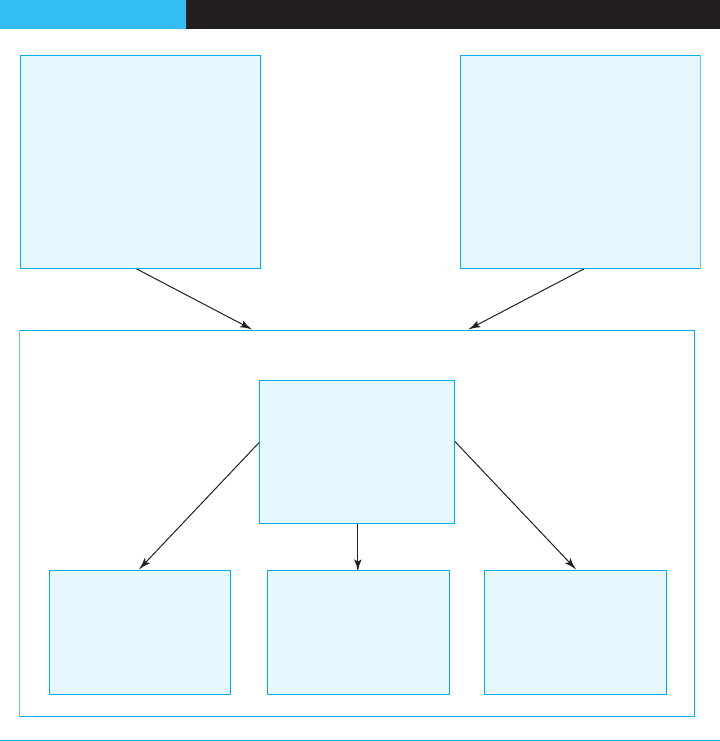

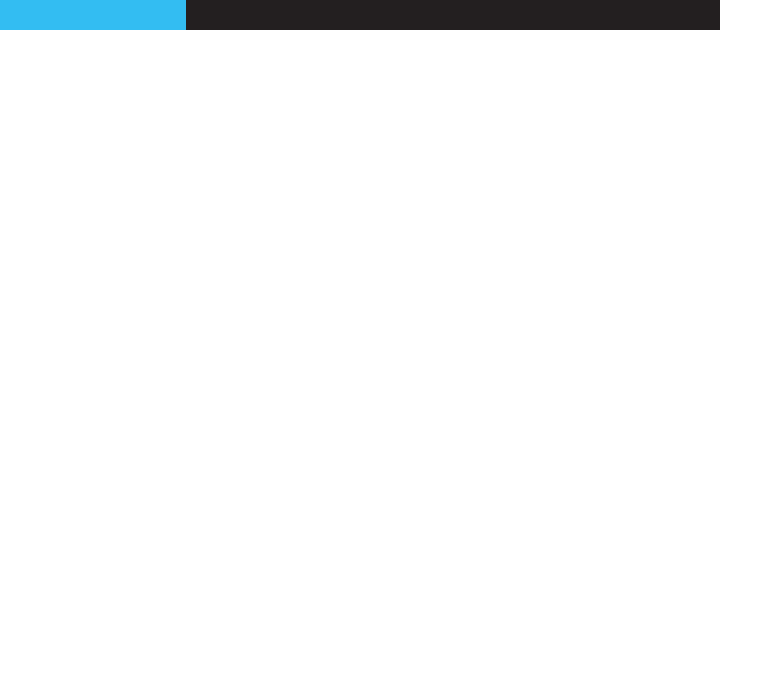

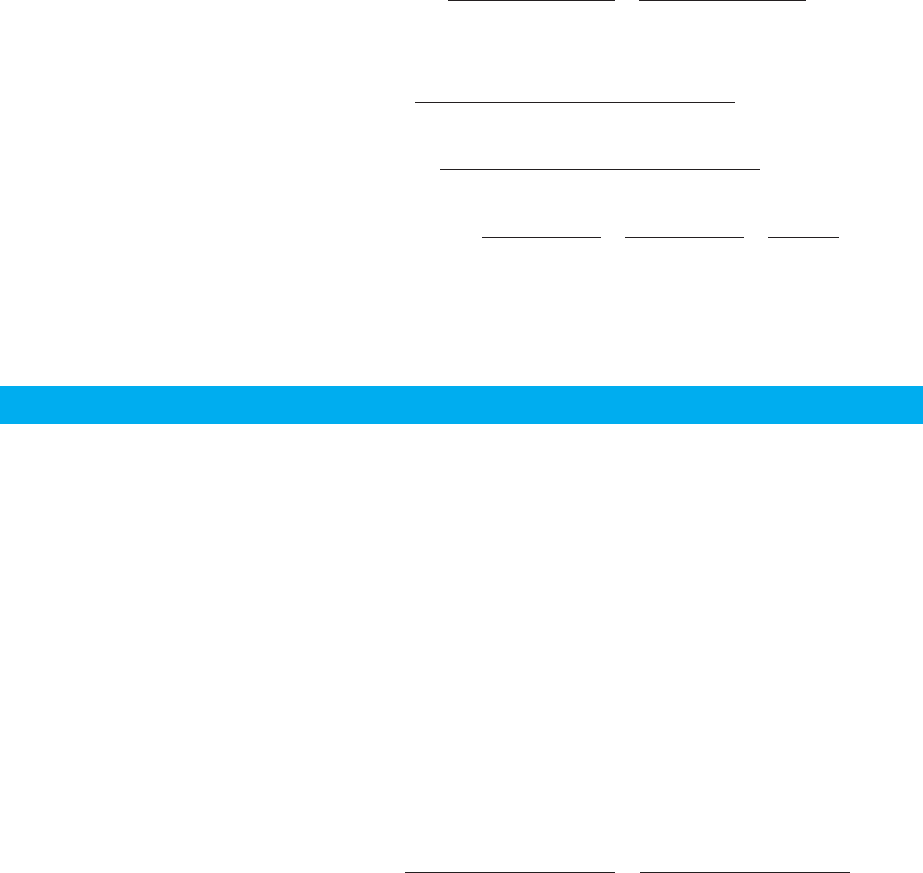

sequences of the firm’ s investment and operating decisions. Figure 1-3 provides a sche-

matic overview of how business intermediaries use financial statements to accomplish

four key steps: (1) business strategy analysis, (2) accounting analysis, (3) financial analy-

sis, and (4) prospective analysis.

Analysis Step 1: Business Strategy Analysis

The purpose of business strategy analysis is to identify key profit drivers and business

risks, and to assess the company’s profit potential at a qualitative level. Business strategy

analysis involves analyzing a firm’s industry and its strategy to create a sustainable

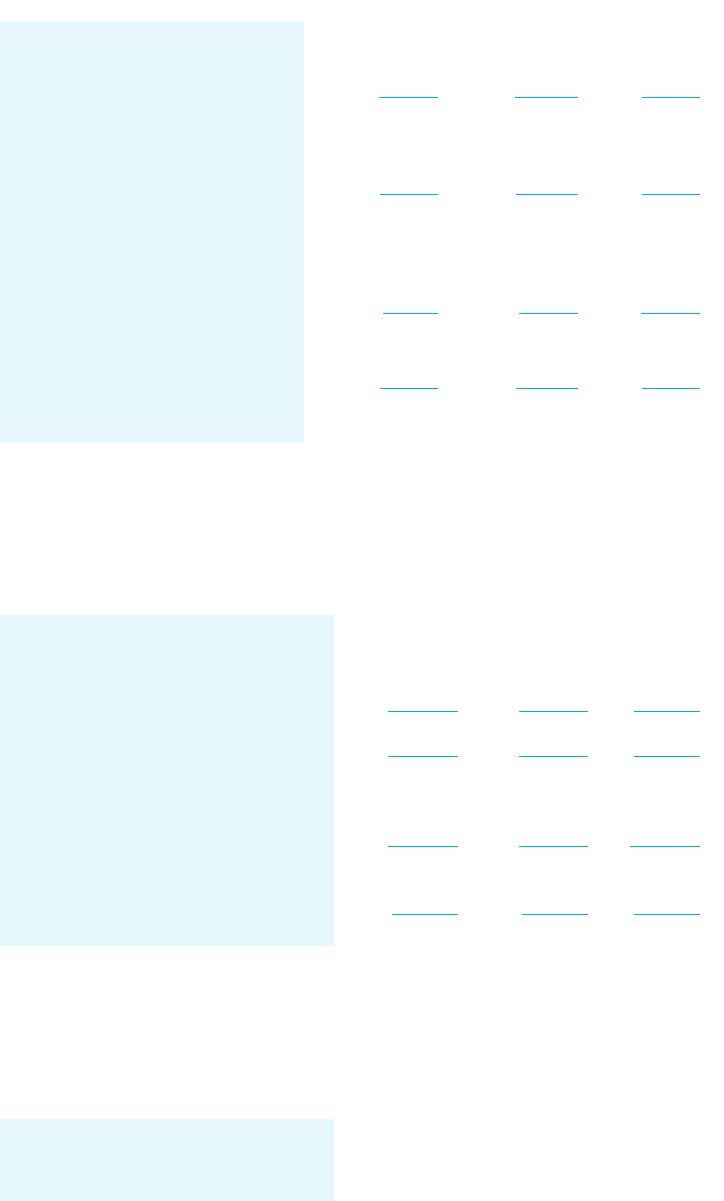

FIGURE 1- 3 Analysis Using Financial Statements

Financial Statements

Managers’ superior information

on business activities

Noise from estimation errors

Distortion from managers’

accounting choices

Other Public Data

Industry and rm data

Outside nancial statements

Business Strategy

Analysis

Generate performance

expectations through

industry analysis and com-

petitive strategy analysis.

Accounting Analysis

Evaluate accounting

quality by assessing

accounting policies and

estimates.

Financial Analysis

Evaluate performance

using ratios and cash

ow analysis.

Prospective Analysis

Make forecasts and

value business.

Business Application Context

Credit analysis

Securities analysis

Mergers and acquisitions analysis

Debt/Dividend analysis

Corporate communication

strategy analysis

General business analysis

ANALYSIS TOOLS

Source: © Cengage Learning

A Framework for Business Analysis and Valuation Using Financial Statements 1-11