Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 1

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

CHAPTER THREE

GENERATING

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

“There are plenty of good five-cent cigars in the country. The trouble is they cost a quarter.

What this country needs is a good five-cent nickel.”

Franklin Pierce Adams

I. GENERATING ECONOMIC/ NORMALIZED FINANCIAL

STATEMENTS

A. OVERVIEW

Performing a thorough analysis of the historical (and resulting economic) financial statements

of a business is prerequisite to performing a meaningful and thorough valuation. Basic financial

statements include the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows. A

thorough analysis of these statements

1

is required in any valuation of a closely held business or

business interest. A complete financial analysis of the business will assist the analyst in many

ways including, but not limited to, the following:

1. Helping to identify strengths and weaknesses of the business

2. Helping to identify trends of the business over time

3. Allowing the valuation analyst to compare and analyze the subject company’s historical

performance and providing a basis for comparing the business to other similar businesses or

industry averages

4. Help identify areas for potential normalizing adjustments

A thorough financial analysis will allow the analyst to draw conclusions relating to key

financial variables critical to the valuation of a closely held business while allowing the analyst

to quantifiably support those conclusions. Financial analysis should be initially performed prior

to making economic adjustments, as an aid in identifying potential areas of adjustment.

Financial analysis should also be performed after adjustments are made.

B. NECESSARY INFORMATION

In order to perform an adequate financial analysis, the analyst will require certain information

from the client. This information should include, but not be limited to:

1

NACVA’s valuation software, called Business Valuation Manager Pro (BVMPro), is a good place to start your valuation’s financial analysis.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

2 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

1. Financial information (historical and prospective) and other similar data on the subject company

2. Factual history of the company

3. Information about perceived competitors

4. Management’s expectations and perceived strengthens and weaknesses

The analyst should use a checklist when requesting and obtaining documents and information.

A sample checklist is included in Appendix IV of this manual. Even though the analyst may not

require all of the items on the checklist, or may require some additional items, a checklist

should still be used as an aid to organization and administration over this portion of the

engagement.

The availability of audited or reviewed financial statements (as opposed to compiled statements

or tax returns) sometimes leads the analyst to place a high degree of confidence in the

statements. However, as will be discussed later in this chapter, GAAP rarely equates to true

economic value. Therefore, adjustments for purposes of valuation are often made to even

unqualified audited financial statements.

There is no universal method for analyzing a company’s financial statements. Each analyst will

begin at a different point, but no area can be skipped. It is important for the analyst to evaluate

all the information provided so a decision to use or not to use any of the data is conscientiously

and deliberately made.

C. ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

It is often assumed that a good estimate of the value of a closely held business can be made by

merely looking at the company’s most recent balance sheet or income statement. This is

certainly not the case. It is commonly accepted that most financial statements, even if prepared

using Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or using a Tax Basis of Accounting

(TBA), often present a picture that is very different from economic reality.

As a result, the analyst will generally prepare economic or “normalized” financial statements.

Normalized financial statements will allow the analyst to better compare the subject company’s

financial performance and position to similar companies or industry averages. It also allows the

analyst to better measure true economic income, assets and liabilities.

1. Objective

The main objective for recasting or adjusting the financial statements of a closely held

company can be stated as follows:

Practice Pointer

Rev. Rule 59-60 suggests five years or more of data should be considered; perhaps this figure

was used since it approximated the average business cycle. In this global economy it is

imperative that the valuation analyst understand the subject firm’s business cycle as well as

the local, regional, and in certain instances, the international economy and how these impact

the subject firm’s industry, because accordingly, the period to analyze could be longer or

shorter, based on the analysts’ judgment.

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 3

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

“To adjust the financial statements or income tax returns of a business to more

closely reflect its true economic financial position and results of operations on a

historical and current basis.”

Balance sheet adjustments are made to reflect the current market values of both assets and

liabilities.

Income statement adjustments are made to reflect the true economic results of operation

similar to what a prospective buyer might require to have reasonable knowledge of the

relevant facts. Normalizing adjustments are hypothetical and are not intended to present

restated historical results or forecasts of the future in accordance with AICPA guidelines.

2. Purpose of Economic/Normalized Financial Statements

a) Should be useful for making comparisons to similar business or industry averages

b) Should be useful in making meaningful projections and forecasts

c) Should result in a representative level of benefits

d) Should (as nearly as possible) represent market values of net assets

3. Categories (or Areas) Of Normalization Adjustments

Normalizing adjustments generally fall into these categories:

a) Method of accounting (LIFO, FIFO, Weighted Average)

b) Non-recurring (transactions that are not reasonably expected to recur in the

foreseeable future)

c) Non-operating/operating (this includes removal of non-operating assets and liabilities

and their related earnings and/or expenses from historical financial statements)

d) GAAP compliance

Many normalizing adjustments cross boundaries. The analyst should be alert to the

potential issues.

Common examples encountered by analysts include:

1. Accounting under GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) or TBA (Tax Basis

Accounting) or a combination thereof often results in a distorted picture of economic reality

2. Closely held business financial statements frequently have the following characteristics:

a. Highly aggressive expensing policies to reduce income taxes

b. Historical or cost basis in nature

3. Economic (normalized) financial statements can be costly to generate:

a. Supportable data just may not be available

b. Unfortunately, often results in adjusting those items that are relatively easy to

support or easy to identify. The valuation analyst should spend enough time

interviewing management to identify those areas most likely in need of adjustment.

This will likely require some research to ascertain the norms and eccentricities of the

industry for the subject company

4. Excessive compensation, perquisites, rent and similar effects of current ownership

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

4 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

5. Non-controlling (minority) vs. Controlling interest adjustments

a. Some valuation analysts believe that when valuing a non-controlling interest, those

elements of the financial statement over which the non-controlling interest has no

control should not be adjusted; others debate the appropriateness of adjusting an

owner’s compensation

II. GAAP ACCOUNTING VERSUS ECONOMIC ACCOUNTING

A. GAAP PRINCIPLES THAT POTENTIALLY DISTORT TRUE ECONOMIC VALUE

"...within the framework of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP),

there is some latitude permitted in the preparation of financial statements."

George D. McCarthy/Robert E. Healy

Authors: Valuing a Company Practices and Procedures

1. Historical Cost Principle

2. Revenue Recognition Principle

3. Matching Principle

4. Consistency Principle

5. Objectivity Principle

6. Full Disclosure Financial Reporting Principle

Practice Pointer

With respect to adjustments for a minority interest, if any, valuation analysts must look at how state

statutory laws define “control”.

With the exception of states that have super majority provisions, “control” or “controlling interest”

generally refers to more than a 50 percent interest. A minority shareholder lacks the capacity to

distribute earnings, fundamentally change the structure of the entity, hire or fire management, etc.

Where a majority interest is being valued, valuation analysts will typically make some or all of the

following:

“Control Adjustments” such as:

Adjust compensation and benefits (typically these are non- qualified employee

benefits)

Remove discretionary spending

Adjust for operating inefficiencies

Adjust financial structure (It is important to underscore that debt is not necessarily

“bad” and that the subject company may be under-performing because it is not using

leverage. It is equally important to point out when the subject firm may be “over-

leveraged”.)

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 5

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

7. Modifying (Or Exception) Principle

a) Materiality Concept

b) Conservatism

c) Industry Peculiarities and Practices

d) Cost-Benefit

B. COMMON ECONOMIC/NORMALIZING ADJUSTMENTS

The following are some of the more common economic/normalizing adjustments that a

valuation analyst will encounter when valuing closely held businesses. It should be noted that

the type of historical financial statements used could have a dramatic impact on the number of

economic adjustments that need to be made. These distinctions are more clearly illustrated

when comparing audited financial statements to tax basis or management prepared financial

reports. Tax basis financial statements and internally prepared reports tend to put a greater

emphasis on cash basis accounting.

The following is a list of the areas of possible economic adjustments. The list is not intended to

be all-inclusive. The type and number of adjustments will vary between assignments and will

be dependent upon the facts and circumstances in each case.

It should be noted that the valuation analyst's economic adjustments usually represent departure

from generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). A balance sheet adjustment to a

historical asset or liability will be made to reflect the market value of that item. These

adjustments usually bring net depreciated-historical-cost to market value and are made for

valuation purposes. Such valuation adjustments show the “normalized” market value and can

be offset against retained earnings.

On the other hand, economic adjustments made to the historical income statement do not

necessarily require a corresponding or offset adjustment to the balance sheet. Removal of a

one-time or non-recurring historical expense does not change any balance on the economic

balance sheet. It is, therefore, likely that many economic adjustments to the income statement

can be treated as one-sided entries. However, some valuation analysts will handle these

economic adjustments to the income statement as increases or decreases to retained earnings.

This is common when using valuation software that tracks both sides of the normalized

adjustments. In either case, the valuator must understand the effect these normalized

adjustments have on the normalized income and net-adjusted assets.

The valuation analyst may also need to consider the income tax effects for each adjustment

made. This will depend upon whether or not the value is to be calculated on an after-tax basis

or pre-tax basis.

Practice Pointer

This is an introductory valuation course. Therefore, in this chapter only a few of the most

common normalization adjustments are presented. Candidates should note that an effort is

underway to converge US GAAP and IASB GAAP; the latter is not addressed in this

introductory course.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

6 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

1. Allowances for Doubtful Accounts

Goal: Adjust so that net accounts receivable represent the market value (as of date of

valuation) of such receivables.

The estimate of the allowance for doubtful accounts should be analyzed and adjusted as

necessary. The allowances should be challenged as they apply to either:

a) Trade accounts receivable

b) Notes receivable

This analysis can be done by comparing historical write-off of bad debts to the current

estimated write-off to determine reasonableness. This analysis can also be done by

comparing an aging of receivables to the allowance account in order to determine the

adequacy of the allowance.

2. Notes Receivable

Goal: To reflect the market value (as of date of valuation) of notes receivable.

For a loan by the company to a shareholder the standard practice has been to write off the

Note Receivable against Retained Earnings. This is a generalization. Yet, the valuation

analyst needs to be cognizant of the purpose of the valuation and the facts and

circumstances concerning the note. For example, in a valuation of a minority interest for

purposes of redemption or sale, a productive shareholder note at market rates should not be

adjusted. Another example is a divorce; the note may be a marital asset separately

accounted for by the state court. (Hence, the valuation analyst needs to make the

judgment regarding both shareholder loan receivables, as well as payables, based on

the purpose of the valuation and the facts and circumstances concerning the terms of

the loan.)

Many issues exist with respect to notes receivable, especially when the analyst discovers

such receivables concern related parties. Notes are presumed to be valued at face value

unless the analysis clearly establishes a different value. The following are several

additional issues to consider:

a) Is there evidence of the indebtedness?

b) Is the note secured or unsecured?

c) If secured, what is the note secured by?

d) What factors are established relative to the valuation of notes by estate and gift tax

regulations?

(1) Interest rate

(2) Date of maturity

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 7

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

(3) Full or partial inability to collect

(a) Insolvency of maker

(b) Insufficiency of collateral

(c) Other

i) Comparable sales

ii) Negotiable vs. non–negotiable

e) Are discounts noted for loss of use of money?

(1) Change of interest rates during term of note resulting in FMV being different

than unpaid principal

(2) Does any documentation provide evidence of arms-length bargaining

f) Does the party intend to repay the obligation?

3. Inventory Valuation

Goal: Make adjustments to reflect the market value (as of the date of the valuation) of

inventory.

a) FIFO vs. LIFO (LIFO follows the conservative and matching principles under GAAP)

A common normalizing adjustment involves the valuation of inventories, particularly

when the method of costing inventory is the last in first out method (LIFO). From a

balance sheet standpoint, the first in/first out method (FIFO) may better reflect the

current value of inventory. However, many businesses have adopted the LIFO

method. During periods of inflation, more costs are charged against income under

LIFO, thus resulting in a lower tax liability.

If the valuation analyst determines that an adjustment from LIFO to FIFO should be

made, the amount of the adjustment to inventory is usually the amount in the LIFO

reserve. The corresponding adjustments to income on historical income statements

are the yearly change in the LIFO reserve. That said, many valuators would not adjust

income on a yearly basis for yearly changes in LIFO reserve. Those espousing this

position are of the opinion that the adjustment is not necessary because the earnings

more fairly represent economic earnings in the future.

b) Write down vs. Write-up

The company's write-down, write-off and costing policies should also be analyzed.

These practices will often alert you to other required adjustments. The existence of

obsolete inventory should also be considered. Any appropriate adjustments should be

made here as well. The same consideration for adjustment may be made if the

analysis of costing policies varies from the standard for a given industry.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

8 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

4. Depreciation Methods

Goal: Restate, if necessary, depreciation allowances to reflect true economic depreciation.

However, for comparative purposes restate depreciation to reflect what is commonly found

in the subject company’s industry. This will improve comparability to industry averages.

The company's depreciation methods should be evaluated and a determination should be

made as to the appropriateness of the method used. The analyst needs to keep in mind that

the methods of depreciation a company uses may be tax motivated and may require

adjustments. The analyst should determine what methods are commonly used in the

industry or other similar companies, as well as what estimated useful lives are used.

a) Straight line method

b) Declining balance method

c) Sum-of-the-year’s digits method

d) Units of production method

e) Tax methods (ACRS/MACRS, Section 179, Bonus Depreciation, etc.)

5. Leases (Capital vs. Operating)

Goal: To locate all material assets and liabilities and get these leases into the adjusted net

assets of the company.

If the company being valued has equipment subject to a lease, the analyst should evaluate

the lease and ascertain whether it is properly classified as a capital or an operating lease. A

thorough understanding of Financial Accounting Standards Board Statement 13 (FAS 13),

summarized in Appendix II, will help in making these determinations, and making any

appropriate adjustment.

6. Adjust fixed asset values to reflect appreciation or impairment

7. Capitalizing vs. Expensing Policies

Goal: To adjust to industry standards if needed.

The capitalizing and expensing policies of the company should be analyzed in order to

ascertain whether or not the policies are reasonable. Many companies have very

aggressive policies in this regard and often exceed the limits of reasonableness. Any

adjustments deemed necessary should be made to the economic financial statements. This

should include an analysis of the company’s capitalizing policies with respect to:

a) Fixed assets

b) Inventory

c) Research and development costs

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 9

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

8. Timing of Income and Expense Recognition

Goal: To restate earnings to align the subject company with the industry and thereby

reflect patterns within the particular industry. (Note: A thorough understanding of

industry-specific practices is very important to properly adjust this area of financial

statements.)

The company's accounting methods regarding the timing of income recognition should be

analyzed for reasonableness. One area where this issue is of particular concern and is

likely to surface is in accounting for long-term contracts and installment sales.

a) Long-term contracts

b) Installment sales

c) Completed contract vs. percentage of completion

d) Other

9. Accounting for Taxes

Goal: To recognize a potential deferred tax liability.

When a company maintains its books and records using different methods for financial

statement purposes than for tax purposes, a deferred tax liability is, in some instances,

recognized and booked as a liability. If it can be established that the deferred liability will

not result in an actual liability, this liability may need to be removed.

a) Deferred tax assets and liabilities

(1) Flow-through method

(2) Deferral method

b) Net operating loss carryovers

10. Extraordinary or Non-Recurring items

Goal: To make adjustments to remove one-time and/or non-recurring income and/or

expense items from the historical earnings.

Accounting Principles Board Opinion No. 30 defines an extraordinary item as one that is:

Unusual in nature – the underlying event or transaction should possess a high degree

of abnormality and be of a type clearly unrelated to, or only incidentally related to, the

ordinary and typical activities of the entity, taking into account the environment in

which the entity operates.

Infrequent in occurrence – the underlying event or transaction should be of a type that

would not reasonably be expected to recur in the foreseeable future, taking into

account the environment in which the entity operates.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

10 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

Businesses will occasionally have extraordinary or non-recurring income or expenses.

Some possible extraordinary or non-recurring income or expense items are the result of

settlements of litigation, gains or losses from the sale of assets, gains or losses from the

sale of business segments or insurance proceeds from key man or property casualty claims.

One of the requirements of economic or normalized financial statements is to reflect

earnings on a consistent basis. Therefore, any amounts deemed to be extraordinary or non-

recurring should be removed to properly reflect the economic or normalized results of

operations.

11. Compensation of Owners and Managers, Including Perquisites

Goal: To adjust officer or owner compensation to more closely reflect the reasonable

compensation of a replacement executive.

A frequently encountered adjustment to the economic or normalized financial statements is

for officer and owner compensation. Officers and owners typically compensate themselves

based on what the business can afford. This amount of compensation is generally not

commensurate with the true economic value of the services performed. The amount of the

adjustment, if applicable, is the difference between the actual compensation paid and the

average amount paid to other people in the same line of work in the same industry. Fringe

benefits must be carefully considered in determining the full level of the officers’/owners'

compensation. Information for making such adjustments can be obtained from:

a) Industry associations

2

b) Employment agencies or employment search firms

c) Integra, Risk Management Associates, Annual Statement Studies

3

d) Specific compensation related publications such as NIBM Executive Compensation,

Panel Publishing (800–248–6426)

e) Economic Research Institute

12. Contingent Liabilities (usually not an income stream adjustment)

Goal: To consider including contingent liabilities in the adjusted net assets.

The analyst should attempt to ascertain whether any unrecorded or contingent liabilities

exist. Some examples of these types of liabilities are:

2

KeyValueData has established relationships with several industry associations.

3

Data available through KeyValueData – requires payment of copyright fee.

Practice Pointer

Numerous databases are available to help determine “reasonable compensation.” It is

important to understand the differences between the databases.

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 11

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

a) Pending lawsuit(s)

b) Unrecorded product service liabilities

c) Unrecorded past service liabilities

d) Unrecorded pension plan liabilities

e) Unrecorded accrued warranty liabilities

f) Environmental liabilities

g) Capital gains tax on unrealized appreciation of assets

The financial statements should be adjusted to reflect the effects of any of the above items.

FAS 5 states that any contingent liability, which is both probable and estimable, should be

shown or accrued in the financial statements. Further, analysts should understand the

current case law regarding the recognition of capital gains tax on unrealized appreciation of

assets as it relates to the purpose for which the valuation is required.

13. Operating vs. Non-operating Items

Goal: To identify and remove non-operating assets (and any related liabilities) from the

valuation process.

The analyst frequently encounters items that are non-operating in nature. In most cases, it

is appropriate to value these items apart from the operating portion of the company. If the

analyst values non-operating assets separately, it must be done so as to exclude any income

generated or expenses incurred by the non-operating assets. Related income and expense

should be valued separately from the earnings base capitalized in valuing the company’s

operations.

14. Intangibles

Goal: To identify and value intangible assets (see FAS 141, paragraph A 14 for a list of

intangible assets). In many circumstances, the value of intangibles will be estimated

through their impact on the benefit stream.

III. CONSTRUCTING ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED BALANCE SHEETS

A. OVERVIEW

In establishing a "market value" balance sheet, the analyst must convert or adjust the existing

balance sheet, whether GAAP or Other Comprehensive Basis of Accounting (OCBOA), on a

line-by-line basis. When using the balance sheet to establish the "fair market value" of a

business, the market value of all the net assets and liabilities must be established.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

12 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

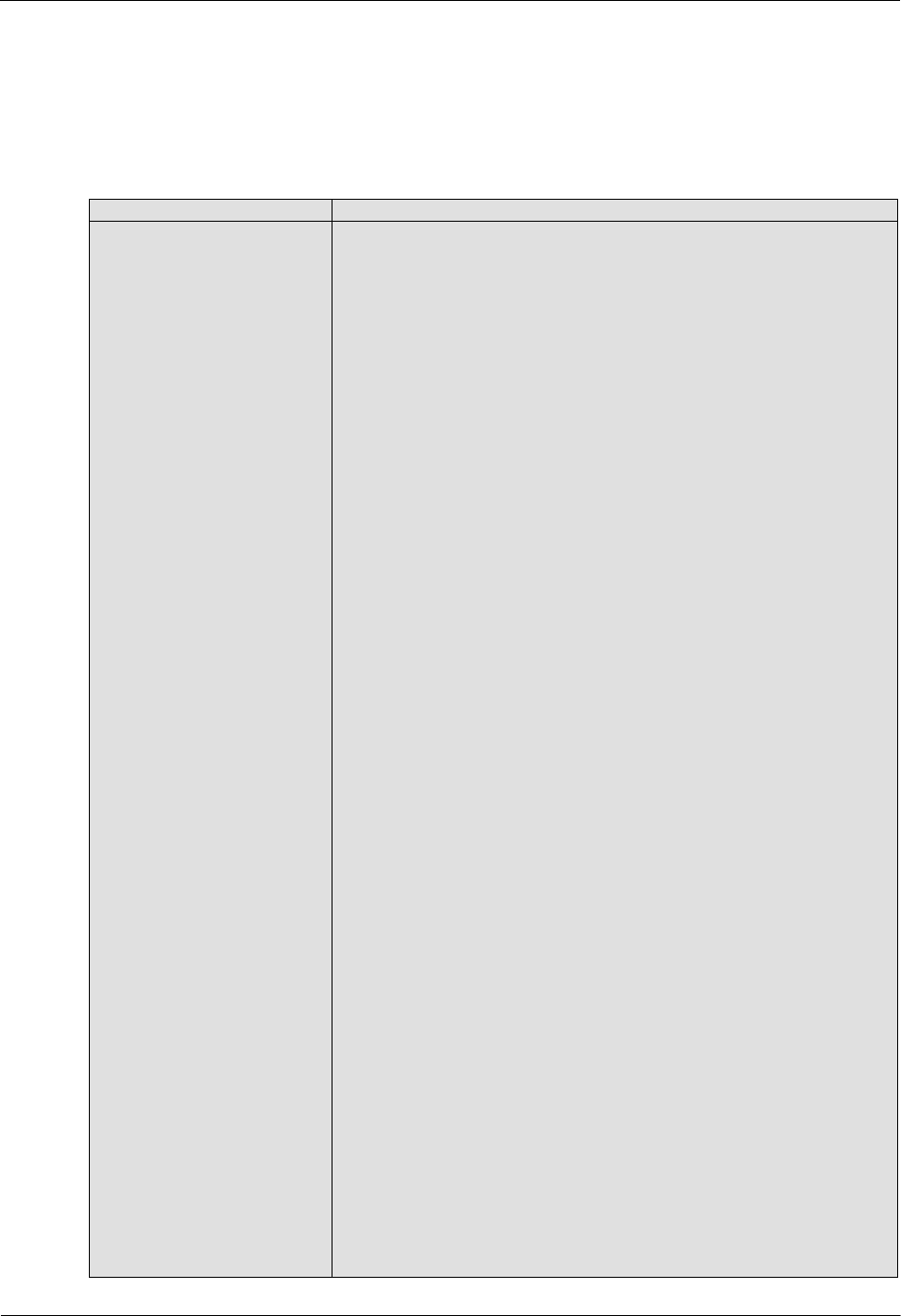

B. ILLUSTRATION

The following chart demonstrates typical adjustments to the Balance Sheet:

Economic/Normalized Balance Sheet Adjustment Procedures

Note: “Replacement cost” refers to the cost to replace an asset under a particular fact situation.

Account Description

Potential Adjustment Procedure

Cash

Adjust for cash in excess of operating needs or consider as non-

operating asset

Trade Note and Contracts

Receivable

Generally, adjust to the amount collectible; remove owner receivable

(although this is not always the case and is dependant on facts and

circumstances); analyze policy for allowance for doubtful accounts.

Marketable Securities

Adjust to market value when appropriate.

Inventories:

Raw Materials

Adjust to replacement cost and write-down unusable inventory.

Work-In-Progress

Adjust to replacement cost; analyze costing procedures/pricing

policies.

Finished Goods

Adjust to replacement cost; analyze costing procedures/pricing

policies; analyze write-down/write-off policies.

Excess Inventory

Potential adjustment if excessive inventory is carried.

Prepaid Items

Adjust to unamortized portion; analyze amortization policies; look for

any prepaid expenses written off.

Fixed Assets

Adjust to market value or estimated depreciated cost to replace;

analyze capitalization policy; analyze depreciation methods.

Leased Equipment

Real Estate

Adjust to replacement cost; analyze FAS 13 criteria and requirements;

tax lease versus conditional sales contract; capital versus operating.

This asset may inflate the operating assets and distort ratios, returns on

assets and capitalization of assets. You should consider whether to

treat the real estate as a non-operating asset and reduce the benefit

stream by any related revenues and expenses.

Intangible Assets:

Goodwill

Adjust to estimated value, using prescribed method.

Patents

Adjust to estimated value, using prescribed method.

Franchise Agreements

Adjust to replacement cost.

Leasehold Interest

Favorable lease-present value of benefit over the term, discounted at

several points above cost of debt.

Deferred Credits/Debits

Analyze for proper inclusion of any deferred tax liability, NOL

carryovers, etc.

Non-Operating or Personal

Assets

Consider removal from statement. Include related debt, if any.

Liabilities

Adjust to actual; analyze figures for unrecorded liabilities, either

realized or contingent.

Capital Gains Tax

Recognize the tax effects from any adjustments in asset values above,

if appropriate.

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 13

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

IV. CONSTRUCTING ECONOMIC /NORMALIZED INCOME

STATEMENTS

A. OVERVIEW

Economic/normalized historical income statements are established for three main purposes:

1. To provide the analyst information for making comparisons.

2. To assist the analyst in making projections regarding future benefit streams or earnings.

3. To serve as a basis for determining/estimating additional value from unrecorded intangible assets

(e.g., goodwill, etc.).

It should be noted that net pre-tax operating profit is often regarded as an important

measurement of income. Therefore, economic adjustments to non-operating income or expense

items may not be necessary. (Note: If the selected benefit stream is pre-tax, be sure that a pre-

tax capitalization rate is used.)

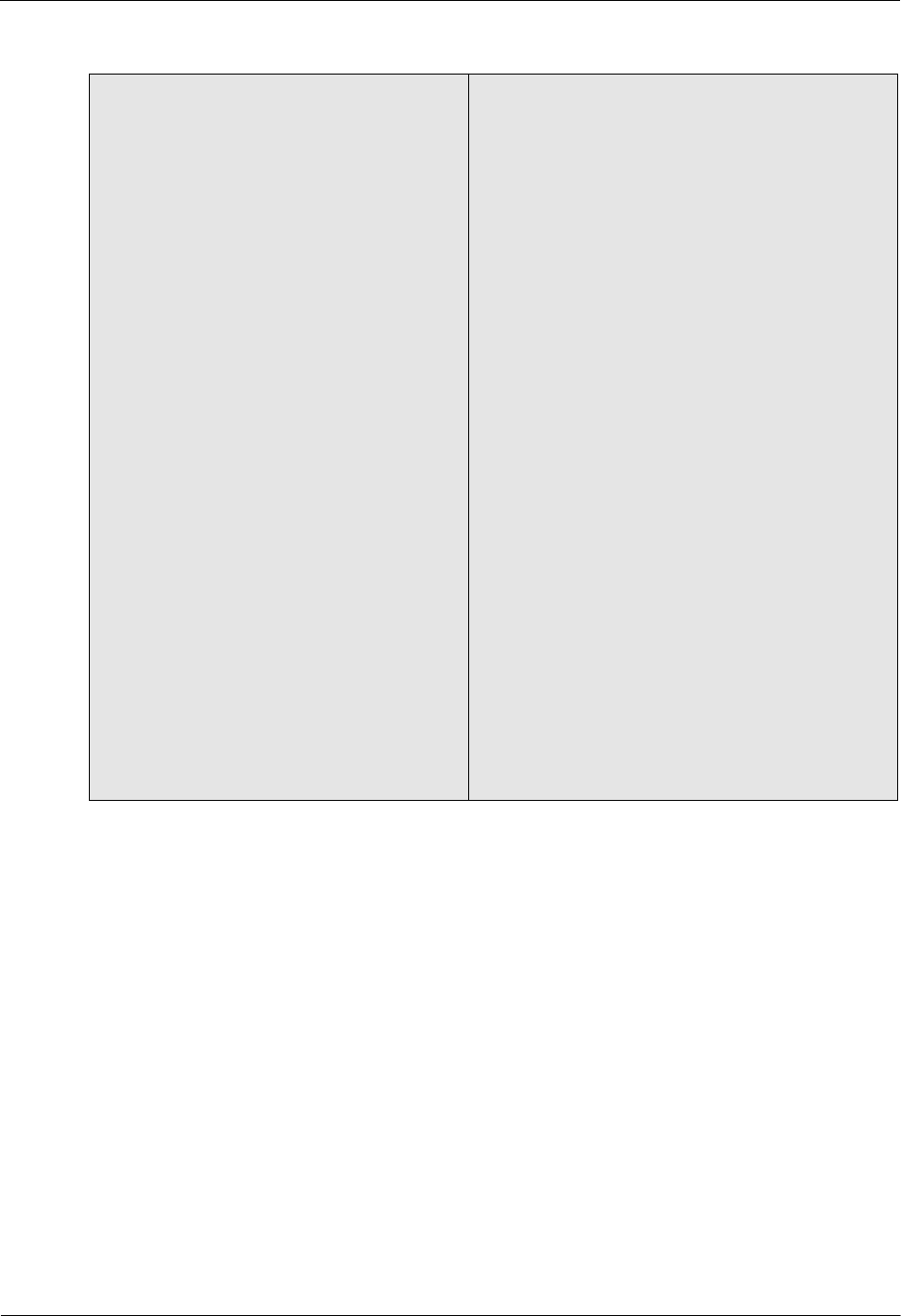

B. ILLUSTRATION

The following chart illustrates possible adjustments to the Income Statement:

Account Description

Potential Adjustment/Procedure

Income

Remove all non-operating income (interest income,

gain on sale of assets, etc.); analyze company’s

policies for recognizing revenue (cash basis versus

accrual basis, completed contracts, etc.).

Cost of Sales

Analyze costing procedures for inventory and

procedures involving write-ups and write-downs.

Any adjustments to ending inventory should also be

reflected as cost of goods sold (CGS). Adjustments

should be made over the same period as the

applicable balance sheet.

Officers’ Compensation

In order to provide a meaningful comparison,

officers’ salaries should reflect comparable market

salaries. This information is often available from

trade associations, personnel managers and others in

the same industry.

Other Salaries

Remove salaries (and benefits if any) of spouses,

children, relatives, friends or others who are not

contributing to the operation of the business.

Travel and Entertainment

Through discussions with the owner or the

company’s accountant, the analyst may discover

travel and entertainment expenses are personal in

nature and do not contribute directly to the operation

of the company. These expenses should be

eliminated to reflect economic earnings.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

14 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

Rent

If the company either owns its own real estate or

rents its facilities from the company owner(s), the

analyst should compare the company’s rent expense

to the market and make any upward or downward

adjustments as necessary.

Professional Fees

Quite often, owners of small businesses have

personal expenses for legal, financial planning and

tax preparation fees charged to their businesses. This

area should be analyzed and adjustments should be

made to more accurately reflect economic earnings.

Employee Benefits

This is an area that is often abused by owners of

closely held companies. These expenses need to be

adjusted to reflect realistic levels of employee

benefits.

Auto Expense

Personal or other non-business automobile expense

paid for by the company should be removed.

Conversations with the owner/manager can often

help to determine the amount of this adjustment.

Depreciation

If it is determined that the method(s) of calculating

depreciation are too aggressive or conservative,

adjustments must be made to more realistically

reflect economic income as well as the economic

balance sheet items.

Other

The analyst should search for other expenses that

benefit the owners/managers that fall outside the

normal costs of operations and make the appropriate

economic balance sheet and income statement

adjustments.

C. INCOME TAX EFFECT ON ECONOMIC AND NORMALIZING ADJUSTMENTS

Many analysts believe it is more theoretically sound to base their valuation and analysis on pre-

tax earnings. One of the main arguments in support of this premise is that a company, through

astute tax planning may be able to avoid in the short term the payment of income taxes. As

such, the after-tax earnings will be the same as pre-tax earnings.

A crucial point to consider in dealing with income taxes is the nature of the investment being

valued. A buyer who is considering acquiring an interest in a company as an asset purchase

should be aware a step-up in basis will be received, resulting in additional depreciation and tax

benefits. In this case, the tax liability for any capital gains will be with the former owner. As

such, the buyer should be willing to pay full market price for the assets (less any commissions

or broker’s fees).

In most instances, however, the analyst is engaged to value the stock of a company to be

purchased by a potential investor. In the case of a stock purchase, the buyer would not receive a

step-up in basis on the underlying assets. In addition, a buyer would be assuming a contingent

tax liability on the difference between fair market value and book value of the underlying assets.

Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

© 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved. Chapter Three – 15

Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training. 2013.v2

Because of both of these factors, the buyer would surely discount any amount paid to the seller

by an amount possibly as high as the contingent tax liability. If the purpose of the valuation is

estate or gift tax, the valuation analyst should obtain an understanding of current case law

regarding the treatment of contingent tax liability on unrealized gains on corporate assets.

In addition to the foregoing chapter of Fundamentals, Techniques and Theory, there are other

sources of information which many professionals in the valuation business have read and/or added to

their library. The valuation analyst, progressing through the steps in a valuation, should be generally

familiar with the body of knowledge represented by this text and other publications. These can

include books, papers, articles, seminars, classes and the experience of a valuation mentor or other

business mentor the valuation analyst may know. Those at the top of the field continue to grow.

Recommended reading includes, but is not limited to:

Burkert, Rodney P., “Adjusting Owner’s Compensation Usually Inappropriate When Valuing

a Minority Interest,” Reader/Edition Exchange, Shannon Pratt’s Business Valuation Update,

June 1998.

Lurie, James B., “Normalization and Control Premiums,” The Valuation Examiner, M/J 2000.

Taub, Maxwell, “Valuing a Minority Interest: Whether to Adjust Elements of a Financial

Statement Over Which the Minority Shareholder Has No Control,” Business Valuation

Review, March 1998, p. 7-9.

Maxwell Taub Article “Valuing a Minority Interest: Whether to Adjust Elements of a

Financial Statement Over Which the Minority Shareholder Has No Control,” Business

Valuation Review, March 1998, pp. 7-9.

ECONOMIC/NORMALIZED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fundamentals, Techniques & Theory

16 – Chapter Three © 1995–2013 by National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA). All rights reserved.

2013.v2 Used by Institute of Business Appraisers with permission of NACVA for limited purpose of collaborative training.

PARTICIPANTS NOTES